DVD Review: Masaki Kobayashi Against the System (Eclipse)

Criterion’s Eclipse line has three general streams: to explore fringe genres, to introduce work by lesser known filmmakers, to present lesser known works by more familiar directors. The latest release, Masaki Kobayashi Against the System, falls into the third category, presenting three early works by the director of the three-part epic The Human Condition (1959-61, previously released by Criterion), plus the film he made the year after completing that masterpiece.

Kobayashi was a leftist opponent of Japanese imperialist militarism who was inducted into the army in the ’30s. Like Kaji, the protagonist of The Human Condition, he resisted promotion; although he had no choice but to serve the Emperor, he refused to give more than the minimum. But despite his leftist sympathies, he had an increasing disaffection for the communist alternative after seeing what happened to Japanese prisoners held by the Russians. Caught between these two poles, he became a humanist filmmaker rather than a political one and many of his films focus on criticisms of Japanese society, while leaving the audience to consider their own solutions for the problems he presented.

Kobayashi apprenticed, and eventually became a director, at Shochiku, the studio of Ozu and Naruse, Kinoshita and Mizoguchi. The house style was largely one of period films, family dramas, and often in the hands of its best directors delicate dissections of Japanese social attitudes. Living through the war and the subsequent American occupation, Kobayashi developed harsher views and the style of the films in this Eclipse set is more aggressive, often paradoxically revealing (like the films of Koreyoshi Kurahara in a previous Eclipse release) the influence of noir and jazz imported from the States. These films are full of dark shadows and moral ambiguity, virtually every character touched to a greater or lesser degree by the social corruption which followed the collapse of the Japanese Empire.

The Thick-Walled Room (1953/56)

Following his directorial debut in 1952, with a family-focused comedy-drama, Kobayashi launched his critical work with The Thick-Walled Room (1953), a film which so troubled Shochiku that the studio suppressed it for three years for fear of offending the U.S., even though the occupation had formally ended in 1952. This film, the first scripted by the novelist Kobo Abe, best known for the four features he wrote a decade later for Teshigahara, deals with a very sensitive and troubling subject: Japanese soldiers condemned by the Allies for war crimes. Abe and Kobayashi focus on ordinary soldiers, not figures of higher authority; yet while they do not excuse these men, they use them to draw attention to the hypocrisy which let many of those with more responsibility off the hook.

Although the film presents a group portrait, dealing with the occupants of a single prison cell, it eventually settles on the story of one man, Yokota (Ko Mishima). We learn in flashback that on a remote island his commanding officer ordered him to go back and kill a villager who had just shared food with his patrol; Yokota objected because the man had been friendly and helpful, but the officer insisted that he was probably a partisan and would betray them. After the war, Yokota was accused of murdering the man and the officer testified against him, saying that he had killed the villager and stolen his food to keep for himself. The officer went free and Yokota was convicted.

Shochiku’s fears of giving offence arose largely from concern that the film might be seen as justifying or excusing the actions of Japanese soldiers in the Pacific, but while Abe and Kobayashi present these men as trapped within a brutal system which forced them to act barbarically, the filmmakers do not let their characters avoid responsibility; in fact all the men are plagued by their consciences and suicide attempts are fairly routine in the prison.

Kobayashi’s main concern is with showing that the Japanese establishment, having used these men for its imperialist aims during the war, was rebuilding itself in the post-war years by pushing the responsibility for atrocities onto the least powerful participants. There’s a scene in which a high ranking officer addresses the prisoners, making a point of telling them that while he himself is a “political prisoner”, they are common criminals.

The film deals largely with Yokota’s efforts to come to terms with his own guilt and redefine himself outside the identity his society has imposed on him and then betrayed.

I Will Buy You (1956)

It was three years after the suppression of The Thick-Walled Room, and a retreat to more studio-friendly projects, before Kobayashi made his next attempt at some harsh social criticism. This time, however, he chose a “safer” subject unconnected with the war and recent Japanese history. I Will Buy You (1956) deals with the efforts of scouts for several professional baseball teams to sign up a star college player, Kurita (Minoru Ooki). Kishimoto (Keiji Sada), the ambitious scout for the Toyo Flowers, narrates the story, giving us a protagonist not unlike Tony Curtis’s Sidney Falco in The Sweet Smell of Success, a cynical, driven schemer who never stops to consider the moral costs of his pursuit of money and success.

Paradoxically, by stepping back from the more overt political implications of The Thick-Walled Room, Kobayashi had found a vehicle for examining Japanese post-war society in far more scathing terms. Severed from its past by the war and defeat, the country found itself in a social and cultural vacuum which was now being filled by an obsession with money. Sheer greed drives Kishimoto and his rival scouts, the team managers, and Kurita’s mentor and de facto manager Kyuki (Yunosuke Ito). Set against all this scheming is Kurita himself, who remains something of a symbolic figure, a young guy who loves his game passionately, but as seen through Kishimoto’s eyes stands as an object to be conquered and possessed. Only Kurita’s girlfriend Fueko (Keiko Kishi) seems to hold any moral perspective on events, wanting Kurita to remain unspoiled by the material frenzy around him.

Black River (1957)

Kobayashi’s next film, Black River (1957), broadens its view with a story centred on the inhabitants of a slum building just outside the U.S. Atsugi naval air base. The jazzy score and Saul Bass-like opening titles declare the underlying theme of American influence on post-war Japanese society, the ramshackle apartment building standing in pathetic contrast to the broad gate of the base which always seems to dominate the background. If anything, Kobayashi’s vision here is even more savage than in the previous film; the characters are scavengers around the edges of American wealth, using and abusing each other in their desperate efforts to make a buck.

At the start, student and bookseller Nishida (Fumio Watanabe), moves into the building, observing the squabbling tenants while trying to remain separate from them. He falls for Shizuko (Ineko Arima), a waitress who lives in the neighbourhood; but she has also drawn the attention of local yakuza Killer Joe (Tatsuya Nakadai, who had made his debut in a small role in The Thick-Walled Room and would later star in The Human Condition). Joe schemes with his gang to grab and rape Shizuko; given Japanese social attitudes, Shizuko responds to her own shame by becoming Joe’s girlfriend, while Nishida still pursues her. Meanwhile, Joe and his political boss scheme with the tenement’s owner (Ishizu Yamada in the film’s most grotesque performance, a character so twisted with greed and opportunism that she’s become physically monstrous) to drive out the tenants so that the building can be bulldozed and replaced with a brothel.

There are many similarities between Black River and Shohei Imamura’s Pigs and Battleships (made four years later), but Kobayashi once again takes a humanistic approach, focusing on the characters and their relationships rather than the more overt political dimensions dealt with by Imamura. The politics are implicit here, but the dramatic interest is in how those politics distort and destroy individual lives.

The Inheritance (1962)

The final film in the set, made immediately after the massive four year effort of The Human Condition, reveals a radical shift in style if not attitude. While the ’50s films show the distinct influence of American film noir, The Inheritance (1962) opens with a very European flavour. The clean, dynamic widescreen images track the elegant Yasuko (Keiko Kishi) through streets where traffic is watched over by store windows displaying expensive merchandise. We seem to be in the Japanese equivalent of La Dolce Vita (made two years earlier), but Fellini’s louche decadence seems mild compared to the acid cynicism Kobayashi displays here.

While window-shopping for jewelry, Yasuko is approached by a smiling but somehow threatening man (Jun Hamamura) who insists that she join him for a drink. As they sit in a restaurant, her voiceover expresses her disgust with the man as she drifts into a flashback to a couple of years earlier, when she was the secretary for businessman Senzo Kamara (So Yamamura). This unpleasant man is married to the venal Satoe (Misako Watanabe) and surrounded by sycophants who cling parasitically to him despite his generally abusive behaviour, including the man who has accosted Yasuko in the opening scene, who turns out to be Senzo’s corrupt lawyer.

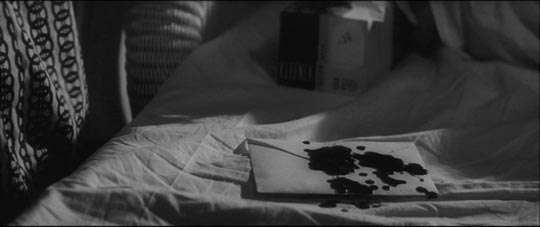

Diagnosed with cancer, Senzo gathers everyone together and declares that he is revising his will; a third of his estate will go automatically by law to his wife, but the rest will go to social causes – unless they can track down his three illegitimate children and bring them to him. If he likes any of them, he’ll leave them part of his legacy. This quest unleashes the floodgates of greed in everyone involved, resulting in multiple levels of deception, rape and murder. Perhaps the key image of the film comes quite late, after Yasuko has rejected an envelope full of money which Senzo tries to force on her; as he falls back in his bed, he coughs up thick dark blood over the pristine white envelope.

While Kobayashi had used the wide screen for epic landscape effects in The Human Condition, in The Inheritance, much of which takes place inside small rooms, the carefully composed frames reflect the cramped psychology of the characters, and the episodic nature of the narrative allows the director to play with different styles and genres. There are elements of noir, which is not surprising, but also of the distinct Japanese delinquent genre of “sun tribe” films, epitomized by Ko Nakahira’s Crazed Fruit (1956).

The Inheritance shows the increased confidence Kobayashi had gained through the years of making The Human Condition; there’s a visual precision to the film which is combined with a sense of stylistic play which gives The Inheritance an ease which belies the savage darkness of its content. He immediately followed it with Harakiri, his bleak deconstruction of the chambara genre, projecting his dark view of Japanese culture into the past.

Criterion’s Masaki Kobayashi Against the System is a valuable addition to their Eclipse line, providing some interesting context for Kobayashi’s better known films.

Not surprisingly, although the transfers themselves are up to Criterion’s usual standards, with rich blacks and fine image detail, the unrestored source prints vary in quality, with the earliest film, The Thick-Walled Room, showing quite a bit of surface damage, and The Inheritance offering the sharpest and cleanest picture. Audio on all the films is clear and accompanied by optional English subtitles, and as usual each film is supplemented by a short but useful contextual essay, in this case by Michael Koresky.

Comments