Miklós Jancsó and the abuses of power

Miklós Jancsó is one of the key figures of Hungarian cinema, but my first encounter with his work didn’t go well. In fact, when I saw the first two parts of his unfinished Vitam et Sanguinam trilogy at the 1981 Hong Kong International Film Festival, I so disliked them that I made no subsequent efforts to see any more of his work. Hungarian Rhapsody and Allegro Barbaro were visually stunning with their rich colours and their elaborate, sweeping long-take camera movements, but their content was so abstract, so divorced from any notion of drama, that they left me completely exhausted and irritable. When I read bits and pieces about his work later, the emphasis always seemed to be on these elaborately choreographed movements of abstract masses of people which somehow represented ideas and incidents rooted in Hungarian history. I remained uninterested.

But I also occasionally read references to his earlier films which made them sound more intriguing, so when several years ago Second Run in England brought out a box set of three of his films from the ’60s – and since at that time I was rather obsessively collecting more esoteric and unfamiliar DVDs – I ordered a copy. But not surprisingly, it has remained on the shelf while I’ve watched hundreds of other films which had a greater pull on my attention.

After completing my recent posts about the dialogue I’ve been having with my friend Gord Wilding about the paradoxical difficulty of maintaining a serious interest in watching movies as we bury ourselves in disks and become increasingly distracted by the Internet, I finally took down the set and started watching. And, as I’ve noticed occasionally in the past, having reached and forced myself through a point of resistance, I found myself not merely engaged, but enthralled by two masterful films over two successive evenings.

Although both My Way Home (1964) and The Round-Up (1965) shy away from psychologizing their characters, observing behaviour with a cool but intensely focused attention, a kind of scientific detachment, they both engage with the physical and social reality of their respective periods with a committed sense of realism totally unlike the later films’ abstraction.

Stylistically, these films belong firmly to that Eastern European tradition of longer takes and complex camera choreography which create the impression of a fully grounded material world within which the action unfolds, a realism which paradoxically can support all manner of metaphorical content – something clearly seen in the work of Tarkovsky and Jancso’s fellow Hungarian Bela Tarr. In these films, material textures, the subtle qualities of light and weather, are as important as the actions of the human beings whose existence in the spaces depicted is transient and frequently fragile.

My Way Home (1964)

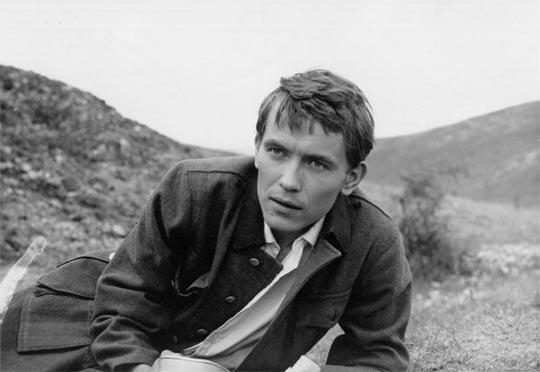

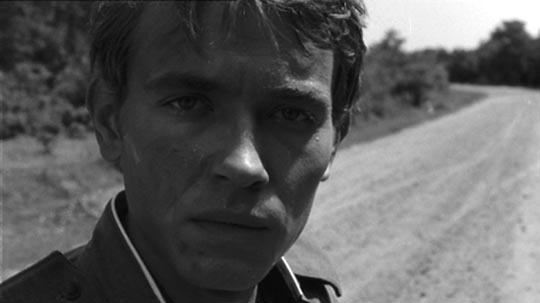

In Jancsó’s third feature, after a decade of shorts and documentaries, a young Hungarian student (Andras Kozak) makes his way across an empty landscape with a small group of people who are suddenly scattered by a troop of mounted Cossacks. As the others are shot, the student is taken prisoner to a camp overseen by Russians. These are the last days of World War Two, and Hungary was an ally of the Nazis. Although we never clearly learn whether the student was in the German army, or in the Hungarian army allied with the Germans, the fact that he’s Hungarian makes him suspect. And yet, in a purely arbitrary moment due to the miscounting of prisoners, the guards turn him loose and tell him to go home.

Alone, he sets out across that empty landscape, picking up a German soldier’s coat to keep him warm along the way, only to be caught again by different Russians. This time, he is sent away to a small hut where a young Russian soldier (Sergey Nikonenko) tends a herd of dairy cows, providing milk to the local camp every day. Neither of them speaks the other’s language and they have to communicate with gestures and tones of voice. The student tries to run away, unable to read a sign warning of a mine field; the Russian saves him and brings him back. They share a ruined hut, milk the cows together; their initial distrust and uneasiness can’t be sustained in such close quarters and gradually their differences become meaningless – they’re two boys and, with war far away, they become playful, they become friends.

The Russian saves the student when a small group of Jewish refugees pass on foot and, seeing his German clothes, start to beat him. One day, they see several women bathing in a nearby pool and like two young animals they chase one of them across the rolling hills, but she’s faster and finally gets away.

But the Russian suffers from a belly wound, the bullet still inside him, and he grows sicker, in constant pain. The student is unable to convey the situation to the soldiers who drive by every day to pick up the milk. As the Russian lies in a fever, the student looks for help, coming across several wagons of refugees; unable to communicate with them, he takes one at gunpoint, hoping he might be a doctor, but when they arrive at the hut, the Russian is already dead.

The student walks away once more, heading for home yet again. Now wearing a Russian coat, he arrives at a railway station where refugees pour out of the surrounding woods to climb onto a train. He pulls himself up onto the roof of one of the cars where an old woman, mistaking him for a Russian soldier, offers him something to eat. But just as the train is about the leave, the people from the wagons he stopped earlier see him and, also thinking that he’s Russian, they pull him off the train and savagely beat him. An aerial shot tracks him as he gets to his feet and starts to run back into the woods, a lone figure in the landscape. In the final shot, he turns and looks into the camera, a boy haunted by experience who now seems terribly old …

In this first masterwork, we can see Jancsó’s big theme: the arbitrariness of political violence and the contingency of social identity, a theme more savagely realized in his next film.

The Round-Up (1965)

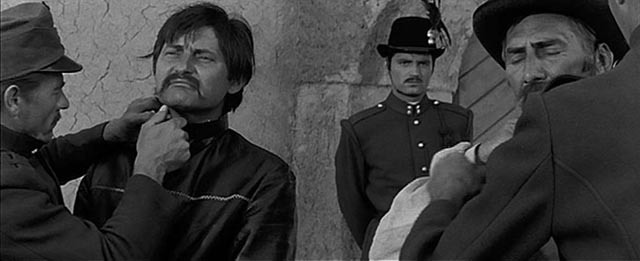

Although The Round-Up retains the sharp attention to the material details of place, this depiction of events following a failed Hungarian uprising against the Austrian Empire in 1848 is more oblique than the earlier film, already hinting at the abstraction of Jancsó’s later work. Set in a high-walled prison compound located in an endless plain which perpetually teases with the idea of space and freedom, the action takes on an almost ritualistic rhythm. Austrian officers are looking for the leaders of the uprising and they methodically work on the prisoners, trying to pry bits and pieces of information from them.

When they manage to make one man crack and confess to having murdered three land-owners, they tell him that if he can find someone who has killed more, they will let him go. Desperate, the man tries to insinuate his way into the confidence of other prisoners, provoking distrust and contempt. When he finally manages to expose another man who has supposedly killed six, he only manages to get three names from him – not enough to claim his own freedom.

The action moves back and forth between the compound, an outlying building where the interrogations take place, and the open plain, Jancsó’s camera observing with cool detachment as hope briefly rises and is quickly crushed. A prisoner is turned loose; we watch through a doorway as he starts to run into the vast empty spaces of the plain; as he grows smaller and smaller in the distance a shot is fired by a man unseen just outside the door frame and the prisoner drops to the ground. A peasant woman is savagely beaten by a group of soldiers in an attempt to get one of the uprising’s leaders to expose himself. As she dies, several men throw themselves to their deaths from the compound walls.

Eventually, the officers change tactics and, discovering that a couple of the prisoners were in the rebel cavalry, they provide the men with horses to display their riding skills. Impressed, they offer an opportunity to form a cavalry unit of their own, with amnesty for the men who join. The prisoner calls all the men who once followed him out of the crowd … at which point, the rebels now exposed, the Austrians execute them all.

The Round-Up is a chilling depiction of the methods by which political control is established and maintained, using men’s strengths and weaknesses against themselves. There is no ideological argument presented; power exists for its own sake, its whims arbitrary and invariably cruel. But like so many films made behind the Iron Curtain, there is an implicit critique of Soviet power disguised by the historical setting. After all, this film was made just nine years after the Russian tanks rolled into Hungary and crushed the revolution of 1956. But already, Jancsó is working towards a kind of abstract generalization about the operations of power, anchored here by historic specificity, but by the time of Hungarian Rhapsody and Allegro Barbaro occurring purely in a conceptual space and thus drained of this film’s visceral power.

Comments