Mad Max: from B-movie to Myth

Even after thirty years, George Miller’s Mad Max trilogy remains one of the most interesting and impressive series in popular cinema. A pity then that Warner Brothers didn’t take the opportunity of their recent Blu-ray box set to offer some kind of comprehensive retrospective account of the films’ making and their impact on action movies worldwide. The set repeats some of the features from the 2001 MGM DVD of the first film (including a commentary and a skimpy half-hour featurette about the “phenomenon”, but omitting another featurette on Mel Gibson) and the commentary and Leonard Maltin introduction from the 2007 Blu-ray of the second film, while the third disk has nothing but the final film (for the first time on Blu-ray). Would Warners have shown these films more respect if they hadn’t been relatively low budget Australian productions?

Mad Max (1979)

The original Mad Max, released in 1979, was the first feature of former doctor George Miller; while a big success around the world, it was barely noticed in the States where MGM redubbed the entire movie because the distributor thought the Australian accents would be “too difficult” for an American audience.

Made on a very low budget, Mad Max is a deliberate, unselfconscious B-movie. In some unspecified near future, society has broken down and on the edges of a vast wasteland an elite group of cops in supercharged cars fight highway duels with violent nomadic gangs. Max (23-year-old Mel Gibson) is the best driver, a married man with a baby, who loves the chase but is ready to give up his career as a pointless effort to fight against unstoppable social decay.

Inevitably, conflict with a motorcycle gang led by the Toecutter (Hugh Keays-Byrne) leads to escalating violence, and the “white-line nightmare” of the lawless roads shatters Max’s family, triggering a final burst of righteous vengeance. While the film borrows visual tropes from outlaw biker movies going all the way back to Brando in The Wild One (1953, dir. Laslo Benedek) and up through the American International/Corman Hell’s Angels series of the ’60s, Miller’s approach is undeniably conservative rather than rebellious. The hero is a representative of law and order standing against the forces of chaos, and while he’s ultimately driven to extremes, there’s no question of who here is right and who wrong.

In narrative terms, then, there’s nothing particularly remarkable about Mad Max. What is remarkable, in addition to the undeniable nascent star presence of the young Gibson, is the sheer inventive energy of the action sequences. The chases and crashes which are salted throughout the film have a visceral power which derives directly from the combination of a low budget and the at times obviously terrifying risks the stunt team took. Miller gets his camera in close and we can see the bone-crunching impact of every detail of the action. In this respect, the film seems closer to Asian action movies than Hollywood product. It’s these sequences rather than the minimal narrative which signaled Miller’s real strengths as a filmmaker.

*

Mad Max 2 aka The Road Warrior (1981)

Two years later, with three times the budget, Miller and his star returned to the character of Max Rockatansky for an epic follow-up which completely belies its still-small budget. Mad Max 2, aka The Road Warrior (1981), was and remains perhaps the single greatest piece of action filmmaking. It also goes far beyond the perfunctory narrative of the first film to consciously create a myth which borrows from many sources, including Joseph Campbell, samurai film and the western; here, the quickly sketched-in character of the first film becomes an archetypal loner wandering the wasteland, haunted by his tragic past and unable to see any possible future. He lives in the moment, his only concerns minute to minute survival and the search for supplies of gasoline to keep his ex-police Interceptor running. The man who lost his family and then sacrificed his own humanity in furious revenge has become the quintessential man-with-no-name.

Additionally, Miller and co-writer Terry Hayes have worked out a more detailed backstory for the end of civilization. It was never quite clear in the first film what had happened to the world and, amongst the highway chaos, we still got glimpses of ordinary people going about their ordinary lives. In Mad Max 2, the world has really ended. The oil ran out and nuclear war erupted, wiping the world clean.

The theme of the sequel is the various ways the scattered survivors have found to deal with disaster. Max has cut himself off from all feeling. We are given a comic mirror image of him in the Gyro Pilot (Bruce Spence), a character designed to reveal the absurd limitations of this isolation. Then there are the two “tribes” Max and the pilot encounter in the wasteland.

The first, a group trying to cling to some semblance of civilization under the leadership of Pappagallo (Mike Preston), have built a ramshackle fortress around a working oil well, gathering and refining the precious commodity in preparation for a planned trek thousands of miles to the north in hopes of finding a lush paradise by the ocean.

The second group is an expanded band of marauders similar to the gang in the first film, led by The Humungus (Kjell Nilsson), a masked, seemingly scarred and mutated warlord followed by a band of hyper-fetishized killers. Into this Manichean division of the remnants of humanity, Max inserts himself, initially intent on his own self-interest (he’ll help the good guys in exchange for fuel), but gradually forced to align himself with their cause, realizing that to be human is to commit to some group interest – and of course, only one of these two options is viable. Max regains his lost humanity by helping Pappagallo’s people escape.

Mad Max 2 is very tightly constructed; there isn’t a wasted moment or extraneous detail. The ragged looseness of Mad Max has been replaced by a remarkable directorial self-assurance. In the early sections, Miller shoots the action in mostly wide shots – we stay with Max on a rocky crag as he watches an attack on the oil well far below and we can see multiple points of action involving seemingly dozens of vehicles. This is the kind of thing so easily done with computer imaging now, but back then these elaborate wide shots were staged in real time with real vehicles in a real desert and the impact is still breathtaking.

As the film progresses, Miller moves in closer on the action. We get to know and identify all the participants so that, by the time of the long climactic action sequence (in fact the entire third act is one non-stop display of insanely dangerous action), Miller is able to stage the most incredible stunts without losing sight for a moment of the narrative purpose of every detail. All too often, directors resort to the quick cutting of countless brief shots to create an illusion of action; Miller uses no tricks to fake things – what we see on screen is what really happened on set and this creates the visceral impact which is impossible to achieve with CG, no matter how sophisticated the technology being used.

Very few action movies even come close to this fusion of narrative and technique (perhaps the nearest would be James Cameron with The Terminator [1984] and Aliens [1986]). But despite the almost flawless results achieved in Mad Max 2, Miller and Hayes didn’t simply settle for a rehash when they returned to their post-apocalyptic world four years later for Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985). While the third film falls short in some respects (particularly the action sequences), in others it’s more interesting; the new script elaborates and expands on the consideration of what it means to be an individual and what is either gained or lost by the formation of a society.

*

Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985)

When George Miller and Terry Hayes revived their iconic character for a third film four years later, a lot of viewers seemed disappointed. The new movie wasn’t exactly like the previous hit and fans felt let down. And it’s true that Thunderdome lacks the single-minded narrative drive of Mad Max 2 – drive being the operative word: there is far less here of the vehicular mayhem which made the previous film the action phenomenon it was.

But there were also other factors which seemed to take the new movie some distance from the distinctively Australian character of the first two films. International success had brought with it not only a lot more money (some six times the budget of number two), but also a degree of “internationalization” of the production. The most obvious sign of this was the introduction of an American pop culture celebrity as Max’s primary opponent this time. Tina Turner’s powerful screen presence works as a terrific foil for Max’s taciturn, reluctant heroism, but there’s no denying that her unmistakable American identity disrupts the Australian-ness which had given the first two films their air of freshness, the feeling that we were seeing something entirely new.

In addition, the new money brought in a famous Oscar-winning composer. But Maurice Jarre’s score moves the new film tonally quite some distance from its predecessors. Brian May’s powerful pulp epic music had been vital in not merely supporting the action of the first two films, but also in defining their visceral energy and thus the character of Max himself. Jarre’s score may be more varied, but it lacks May’s drive (yes, that word again!). The jazzy broken rhythms of the Bartertown theme give the place a distinctive character, as do the more ethereal themes associated with the feral children, but the music seems to break the film into separate parts rather than unify its narrative world.

But perhaps more than these breaks with the previous films, what upset the fans was the filmmakers’ decision not simply to reiterate what they’d done previously in terms of action, but rather to focus more on the themes of social organization and the implicit connections and conflicts between the individual and the community.

As in Mad Max 2, Max once again finds himself caught between two distinct societies, but here they’re less clear-cut than the Pappagallo/Humungus division of that film. And that ultimately gives Thunderdome a richer dramatic texture than the first two films. Perhaps in recognition of the effects on the movie of all that foreign production money, the first place Max finds himself when he wanders out of the desert this time is Bartertown, a nightmarish monument to the survival of laissez-faire capitalism in the post-apocalyptic world. Ruled over by Auntie (Tina Turner, the character’s name perhaps a sly reference to Uncle Sam, who to some degree was co-opting the Australian franchise), the inhabitants spend their lives trading anything they can find to each other – including Max’s own stolen property, not to mention fallout-contaminated water.

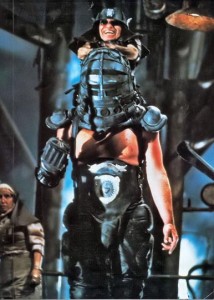

But Auntie’s power isn’t as absolute as she’d like. Beneath Bartertown in a hellish subterranean pit inhabited by the condemned, Auntie’s nemesis Master-Blaster produces all the town’s energy from pig shit (the layers of metaphor about capital and consumerism are constructed with humour and deft visual invention). Master-Blaster – literally split in two, the brains (Angelo Rossitto) riding on the shoulders of the brawn (Paul Larsson) – delights in needling Auntie by calling for embargo at the slightest provocation, cutting off power until she publicly acknowledges that he runs the place.

Max makes a deal with Auntie: for the return of his stolen wagon, he’ll pick a fight with Master-Blaster, agreeing to kill the big body in a fight in the Thunderdome, a huge cage used to settle all disputes by a one-on-one fight to the death. And so the first of the film’s two main action sequences is built around bungee cords, giant hammers and a chainsaw rather than cars.

Having reneged on his deal with Auntie, Max is exiled to the desert where, on the brink of death, he’s rescued by the adolescent girl Savannah (Helen Buday) and dragged back to the film’s second community. A collection of feral children, survivors of a plane crash at the time of the war, live a primitive yet idyllic existence as hunter-gatherers in caves by a lake. Their use of language has deteriorated and they sustain themselves by maintaining an oral tradition about times gone and a saviour who will come and take them back to the world. Naturally, they believe Max is this Captain Walker and when he refuses to accept his mythical role, some of the kids set off across the desert by themselves. Max’s conscience forces him to follow and he and the kids end up back at Bartertown, where they instigate a rebellion in the subterranean pit and escape with Master in an old train which was being used as part of the power plant.

And so, echoing Mad Max 2, the film ends with an extended vehicular chase, but this time tied to the train’s tracks as if Miller were commenting on the enforced necessity of repeating the action he’d already staged in the previous film. The stunt work is still spectacular – and spectacularly dangerous – but it can’t help but feel like deja vu. In fact, that feeling is only amplified by the presence of Bruce Spence (the Gyro Pilot from Mad Max 2) as yet another pilot here, though after some initial confusion it becomes apparent that he’s actually an entirely different character. The fact that the viewer initially believes him to be the same character, while Max shows no recognition, is quite jarring on a first viewing and it’s unclear why Miller would have created this character other than as a gesture of passive aggression towards whatever forces were asking him to repeat himself.

And so, it’s the elements which most closely resemble the previous film which tend to be the least satisfying aspect of Thunderdome, while the elaboration of the two conflicting societies paradoxically make it the deeper and more resonant film – particularly the sections with the children (co-directed by theatre director George Ogilvie who helps impart a convincingly ritualistic tone). The crass materialism of Bartertown contrasts powerfully with the children’s use of memory and myth to evoke an alternative rooted in more human and even spiritual values.

*

Given that by 1985 Miller appeared to have taken the character of Max Rockatansky as far as he could, and given the fact that for more than a decade now he’s directed only children’s movies (the last two, Happy Feet 1 and 2, entirely computer animated), one has to wonder what he’ll make of the upcoming Mad Max: Fury Road (with Tom Hardy in the Gibson role). Considering the nature of the business today, it’s disheartening to think that all that spectacular stunt work may now be simulated by computers …

Comments

Rockatansky? Who knew?!?!?

It’s in the dialogue!

I guess it was obscured by those Australian accents

Guess that’s why MGM originally dubbed it!