Representing Violence: The Manson Family (2003)

Considering the amount of effort and energy required to make a movie, it’s not surprising that a filmmaker can become obsessed with a project. Major directors sometimes get lost trying to complete a movie – think Werner Herzog determined to drag a full-sized steamship over a mountain in Fitzcarraldo, or Francis Ford Coppola growing mad in the jungles of the Philippines as he put everything he owned into completing Apocalypse Now. Interestingly, succumbing to these obsessions often results in films (as in these two cases) which are not their directors’ best work.

For a lesser talent, the corollary may apply: obsession may result in something which transcends the general standard of their work. Such is the case with Jim Van Bebber’s The Manson Family (aka Charlie’s Family), recently released on Blu-ray by Severin. In a career spanning thirty years, Van Bebber has directed only a handful of shorts, some music videos, and two features. The first, shot in his hometown Dayton, Ohio, was Deadbeat At Dawn (1988), a minor piece of regional exploitation featuring gangs, drugs and martial arts. The second is something else again.

Following Deadbeat, Van Bebber and his creative partner Mike King decided to make another feature as quickly as possible and settled on the Manson Family murders. But something strange happened. As Van Bebber dug into research on the case, he quickly became uncomfortable with the idea of doing an exploitation quickie. He immersed himself in the details of the case and ended up spending the next fifteen years completing the film.

The Manson Family, begun in 1988 and finally completed in 2003 (with the help of David Gregory and Carl Daft of Blue Underground), is a minor masterpiece, a fierce work of anti-exploitation determined to put an end to the Manson myth which was codified during the trial thanks to the case made by prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi. The public image of Manson was a combination of his own self-mythologizing and Bugliosi’s elaborations on same.

Charles Manson was a petty criminal who had spent almost twenty years in prison from his teens to his thirties. He had musical ambitions and latched on to the counter-culture lifestyle of the late ’60s, gathering a group of generally much younger kids around him as he espoused the ego-destroying pleasures of sex, drugs and rock’n’roll. Manson and his Family took up residence on the Spahn Ranch while he tried to get his recording career off the ground. He wasn’t very successful (his recordings reveal an interesting but mediocre folk-rock singer-songwriter) and this failure, along with petty criminal activities, pushed him deeper into paranoid fantasies: he was the victim of forces trying to hold him back because he was carrying a revolutionary message.

A run-in with a black drug dealer, Lotsapoppa, which ended with Manson shooting the guy, resulted in him believing that the Black Panthers were after him. He began to arm his followers, ramping up his teachings with warnings of a coming race war (the “helter skelter” that dominated Bugliosi’s case, the name being taken from a song on the Beatles’ White Album). After one of his acolytes, Bobby Beausoleil, was arrested for the murder of former Family friend Gary Hinman, Manson hatched a plan to get Bobby off: he would send Family members out to commit some brutal crimes resembling the Hinman murder, leaving behind clues indicating that they were linked to the coming race war.

Manson told his followers that they were initiating Helter Skelter, but his actual motive was to take suspicion off Bobby just two days after his arrest. And so the Tate/LaBianca killings had a pathetically mundane rationale disguised as something momentously apocalyptic. Bugliosi’s case was built on the apocalyptic rationale, thereby solidifying Manson’s own mythology.

Jim Van Bebber set out to correct this false image of Charles Manson as some kind of dark messiah and rooted his film in the more mundane facts of the case, choosing to focus on the Family members who actually did the killing, seeking to uncover just how a group of rebellious, disaffected middle class kids could become cold-blooded butchers under the guise of personal liberation.

Repeatedly running out of money and being forced to scrounge for more is one of the common torments of low-budget independent filmmaking. But for an obsessed filmmaker, the interruptions and delays can aid in rethinking and deepening the project. This happened to Van Bebber with The Manson Family.

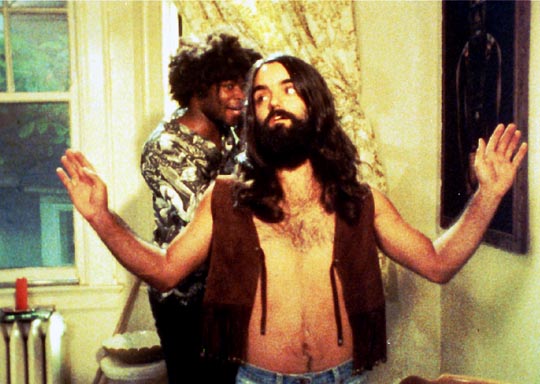

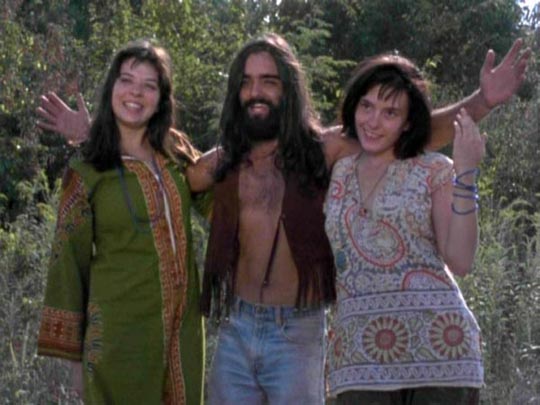

The film has three interwoven elements. The central one, and the first to be shot, covers the events on and around the Spahn Ranch, leading up to the murders. Shot and edited with an uncanny sense of authenticity – the deteriorated 16mm images; the vacuous philosophizing of Charlie and his acolytes – this material plays like a relic of the late ’60s which has been salvaged from the loft of the horse barn. Van Bebber gets naturalistic and very unselfconscious performances from a young, fairly inexperienced cast.

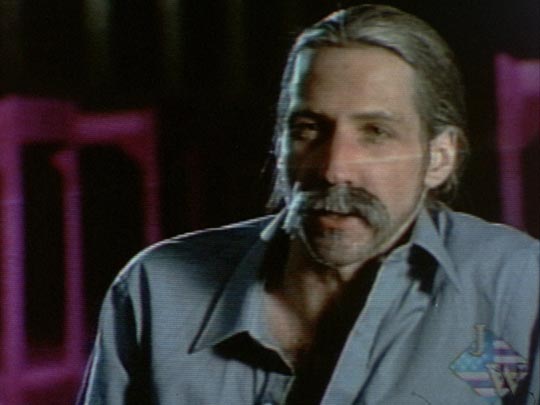

Some years later, he regathered his cast to shoot “television interviews” with key members of the Family serving time for the murders. There’s a big advantage from the delay in that the actors are clearly older now, adding weight to their retrospective comments. But more importantly, Van Bebber uses these interviews both to comment on the events in the earlier material and to deepen our understanding of the killers. We see them straining for self-justification and absolution – at least two of them have “found Jesus” in prison (Tex Watson even becoming a prison chaplain), wondering why society still can’t forgive them since Jesus already has. Van Bebber uses these interviews to expose the kinds of psychological mechanisms which are necessary for ordinary people to become monsters and then subsequently to live with the knowledge of their own monstrous acts. We repeatedly see how the killers have adjusted, distorted or completely rewritten their parts in the activities of the Family.

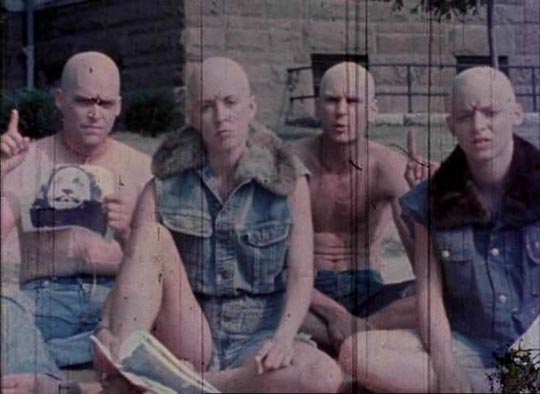

The final element, added late in the production process, is a present-day framing device built around a television producer working on a retrospective documentary, keeping the Manson story alive decades later, reinforcing the cultural memory built on the myth rather than the more mundane truths of the case. Four punkish Charlie fans take exception to the project and, as if infected with a cultural virus, commit their own acts of violence in Charlie’s name.

These three threads, intricately woven together, lead inevitably to the Tate/LaBianca murders themselves. This is clearly the trickiest part of the story to deal with. The film itself acknowledges by its very existence a certain salacious desire on the part of its audience to witness the horror; why else would we come to a movie about Manson and his Family? But here is where Van Bebber’s obsession pays off, his self-imposed commitment to dig down through the sensational mythology to the core reality. By this point we’ve watched the Family evolve from aimless, carefree dropouts to paranoid, affectless tools at Manson’s command. We’ve seen what’s been killed inside each of them.

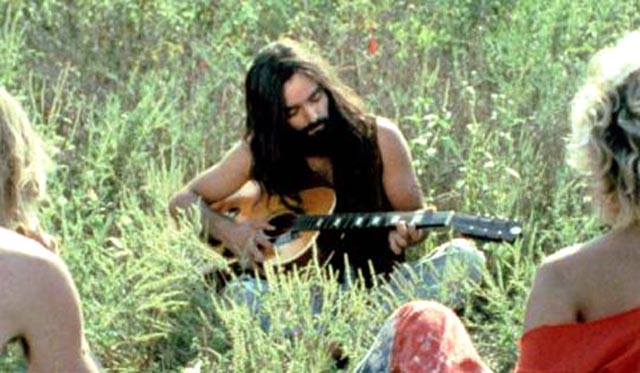

This transformation is represented by an unforced symbolism of sexuality and the body. Early on, Van Bebber evokes a pastoral naturalism tinged with an air of romantic liberation; members of the Family pair off nakedly in sunny meadows, their coupling a kind of communion with nature. Later, as the paranoia takes hold, we see them engaged in a kind of black mass orgy by firelight at night; the sexual frenzy is combined with drinking and bathing in the blood of a sacrificed dog, the druggy imagery evoking the power of demons.

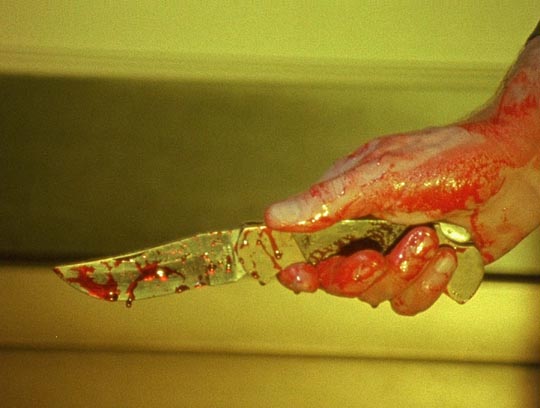

But finally, in the murders themselves, Van Bebber uses a flat, detached, observational style. Where in the typical gore/slasher movie the killings are offered as “money shots”, the thrill we’ve come to experience, with victims objectified and the viewer encouraged to assume the killer’s point of view, Van Bebber refuses this kind of identification. We are forced to watch the horrific acts, the savage destruction of human beings at the hands of people who, rather than having banished their egos and attained enlightenment, are now at the point where nothing exists for them except their own twisted selves – the ends of all that “love and liberation” turn out to be the complete failure to experience any empathy whatsoever.

The murder sequences are appalling, difficult to watch, deeply depressing and ultimately utterly pathetic, devoid of the cathartic release we expect from a typical horror film. The manic excitement of the killers, their treatment of pain and horror as some kind of transgressive comedy for their own amusement, becomes an indictment of the audience’s own desire to watch the slaughter. This is the opposite of what we expect from an exploitation film, taking the elements of a familiar formula and re-rooting them in reality to force a recognition of just what it is we think of as entertainment. Here, at last, we are finally – and justifiably – appalled by the violence on screen.

Some critics of the film complain about the “tastelessness” of the violence. But, as Van Bebber himself asks: how would they like this real-life horror to be portrayed? Would The Manson Family be a “better” film if it had been made in a way which didn’t upset and disturb the viewer? Of course not; our sense of disgust is the ultimate purpose of the film.

Some critics of the film complain about the “tastelessness” of the violence. But, as Van Bebber himself asks: how would they like this real-life horror to be portrayed? Would The Manson Family be a “better” film if it had been made in a way which didn’t upset and disturb the viewer? Of course not; our sense of disgust is the ultimate purpose of the film.

*

The disk: The 1080p 1.33:1 image on Severin’s Blu-ray is an improvement over the standard image of Dark Sky’s 2005 DVD. (The on-screen title of the Dark Sky edition is The Manson Family, but on-screen the Severin edition is titled Charlie’s Family, indicating a different print source.) Although much of the photography is deliberately degraded, with scratches and dirt, the Blu-ray image is sharp, with an accurate rendition of the 16mm colour values and grain. The audio has a low-budget rawness which serves the film well, adding to its overall documentary-like effect, and is offered in both Dolby 5.1 and Dolby Surround 2.0.

The extras: Severin has packed the disk with extras, the majority of which are ported over from Dark Sky’s 2-disk special edition. These include a feature-length making-of, The Van Bebber Family (1:17:00) which gives a fairly comprehensive account of the production, with extensive interviews with Van Bebber, producing partner and director of photography Michael King, and a number of the actors. (The packaging refers to this as the “uncut” version; as it’s less than a minute longer than the one included in the Dark Sky special edition, I’m not sure what the difference is.)

There is also a 74-minute cam-corder documentary about the 1997 FantAsia Film Festival in Montreal, In the Belly of the Beast; this is included because Van Bebber premiered the film as a work-in-progress at the festival. The main focus of this documentary is the sheer difficulty of making very low budget independent movies, but interestingly many of the filmmakers who appear in it seem to be aiming for a transgressive shock-for-shock’s sake effect which contrasts sharply with the seriousness of Van Bebber’s approach. The final carry-over from the Dark Sky edition is a 10-minute selection of interview clips with Manson himself taken from Nikolas Schreck’s Charles Manson Superstar (1989); the former leader of the Family comes across as a hyper-active, self-deluded man who continues to deny his responsibility for what happened in 1969.

The features new to Severin’s disk are: a commentary track from Jim Van Bebber in which he is clearly reluctant to talk about the project – after 15 years working on it, he seems exhausted, having put everything he has to say about the case into the film where it can all be clearly seen. He emphasizes his driving commitment to stick to the documented facts and his constant rethinking and refining of the film as he added elements over the years. The commentary ends at the 66-minute mark and it seems understandable that he wouldn’t want to talk through the graphic third act.

The features new to Severin’s disk are: a commentary track from Jim Van Bebber in which he is clearly reluctant to talk about the project – after 15 years working on it, he seems exhausted, having put everything he has to say about the case into the film where it can all be clearly seen. He emphasizes his driving commitment to stick to the documented facts and his constant rethinking and refining of the film as he added elements over the years. The commentary ends at the 66-minute mark and it seems understandable that he wouldn’t want to talk through the graphic third act.

Then there’s a collection of deleted scenes (14:03) which, having been shot on VHS off the screen of a flatbed Steenbeck editing table, are barely watchable and add little of interest.

An interview (19:51) with Phil Anselmo, of the heavy metal band Pantera, mainly expresses the musician’s enthusiasm for the film. Anselmo contributed to the film’s music and offered support to Van Bebber in finishing the project.

Other than the commentary, the most substantial new feature is a recent short film by Van Bebber called Gator Green (15:47). This is an interesting inclusion because it graphically highlights what makes The Manson Family transcend its original exploitation roots; Gator Green, about three crazed Vietnam vets running a bar where they kill patrons and feed them to the alligators in the nearby swamp, is completely gratuitous. Along with Van Bebber’s earlier exploitation feature, Deadbeat At Dawn, it reveals how the director’s 15-year obsession with The Manson Family pushed him to go far beyond his limitations as a filmmaker to create something uniquely powerful.

Finally, there’s a selection of trailers from both the original 2003 release and the 2013 re-release (9:40).

Comments