Room 237: an obsessive search for meaning

in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining

Rodney Ascher’s Room 237 provides free rein to five obsessive fans who air their personal interpretations of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980). While other people’s obsessions can be fascinating, and conspiracy theories often provide narratives more satisfying than prosaic reality, sometimes, when overexposed, they can become exhausting and irritating. I approached Ascher’s film with a fairly high degree of interest because, as I’ve mentioned before, although The Shining is one of my least favourite Kubrick films, I do keep returning to it as if in search of something I’ve always missed on previous viewings; but, alas, after watching Room 237 I still have no satisfactory answers. Less a documentary than a hallucinatory textual exegesis, at 102 minutes it occasionally tests viewer patience even as it illuminates the strange ways we form bonds with movies that get under our skin.

We never see any of Ascher’s interviewees; they remain disembodied voices from the ether, as we watch endlessly repeated and manipulated clips from The Shining and most of Kubrick’s other films, as well as numerous other movies. The editing is often clever, as it both illustrates and counterpoints what we hear, sometimes supporting arguments, sometimes calling them into question (Ascher makes particularly witty use of Tom Cruise in Eyes Wide Shut). For anyone who has worked in documentary, the big question hanging over Room 237 is just how the heck Ascher managed to get rights to so much material.

Of the five voices, four are male, only one female. I’m not sure whether this counts as a fair random sample of cinephile obsessions, but it does give the impression that women on the whole may be a bit more rational than men.

The five witnesses are: journalist Bill Blakemore, who sees The Shining as an indictment of the genocide perpetrated by Europeans on the Native American population; playwright and novelist Juli Kearns, who seems to have spent a lot of time mapping the Overlook Hotel to reveal its geographic inconsistencies; Jay Weidner, a filmmaker who claims he’s “proved” that Kubrick aided NASA in faking the TV images of the moon landings and that The Shining is his coded “confession”; academic Geoffrey Cocks, who believes that Kubrick filled the film with references to the Holocaust in an effort to make the 20th Century’s most unthinkable horror comprehensible on a personal level; and John Fell Ryan, a writer and musician, who sees the movie more playfully as an argument for the unreliability of film as a representation of reality.

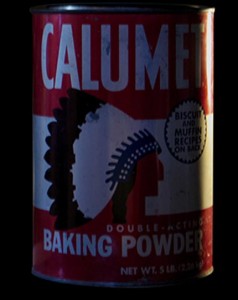

Obviously Cocks and Blakemore’s theories are the heaviest, Weidner’s perhaps the loopiest. All are based on the idea that a) nothing went into a Stanley Kubrick movie which didn’t hold some symbolic meaning for the director, and b) that Kubrick’s obsessions strangely parallel their own. Blakemore says he wasn’t that interested in the film until he noticed cans of Calumet Baking Powder with their Indian head logo in the kitchen storeroom which Halloran (Scatman Crothers) shows Wendy (Shelley Duvall) and Danny (Danny Lloyd); from this and the native burial ground beneath the hotel and the floods of blood erupting from the elevators, he deduces that the film is about white guilt for the devastation of the indigenous population.

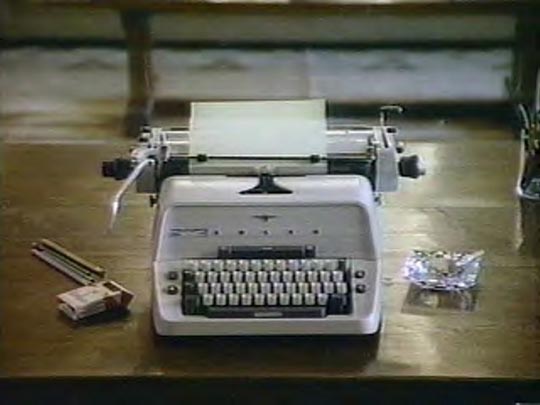

Cocks starts from the typewriter that Jack (Jack Nicholson) is supposed to be writing his novel on; it’s a German model, which for him echoes the typewriters which the methodical Nazi clerks used to make their lists of Jews to be swept away in the Holocaust. When Jack is axing down the bathroom door trying to get at Wendy and Danny, he quotes the wolf from The Three Little Pigs; Cocks notes that the old Disney cartoon presents the wolf as a gross anti-Semitic parody. Early in the film, a slow dissolve superimposes a group of tourists over a stack of baggage in a hallway, apparently calling to mind the mountains of luggage which accumulated as Jews were sent to the gas chambers.

Weidner’s theory about the moon landings seems even more tenuous. At one point Danny wears an Apollo 11 sweater; Kubrick changed the sinister room’s number from 217 to 237, the latter (if multiplied by a thousand) the mean distance in miles between the Earth and the moon. Weidner interprets Jack’s climactic rant at Wendy as the words Kubrick must have spoken to his wife Christine when she found out about the vast deception he had been a party to … Weidner also mentions that NASA is mad that he’s proven the moon footage is fake and that he’s being watched …

So what’s going on here? We all notice details, and we all notice different details, depending on our own experience, memories, points of view. So these interpreters of Kubrick’s horror movie tend to focus on things which are associated with their pre-existing ideas. Blakemore sees Calumet Baking Powder cans, but Weidner’s theory is supported by a shelf of Tang in the same storeroom. What then is the meaning of the boxes of Rice Krispies which fall on Jack when Wendy locks him in that room? And what about all the other items on the shelves? Why is one vitally significant and not another, if Kubrick is critically concerned with every detail? Of course, the simple answer is that the room is well stocked with all the items a large hotel kitchen would need – the art department has made a big effort to create a realistic set in which the action can take place convincingly – and perhaps Kubrick arranged them the way he did because he was concerned about the pictorial qualities of the cans’ colours.

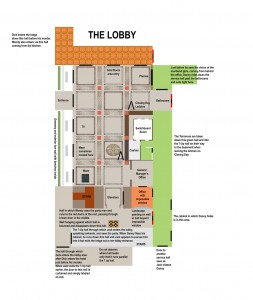

Less portentous but more interesting is Juli Kearns’ obsession with the architecture of the Overlook. By studying the film carefully, she has drawn floor plans which reveal that the sets do not actually make sense. The manager’s office has a large sun-filled window, yet it must be nowhere near an outer wall. The upper floor doesn’t fit properly on the lower. She latches on to a poster seen in one room which apparently is a skiing advertisement (even though, of course, manager Ullman [Barry Nelson] has explained to Jack that the hotel’s location is not suitable for skiing); what she sees is actually the silhouette of the Minotaur, her hunch confirmed by a portrait elsewhere of a Native American wearing a bull’s head, and of course by the presence of the hedge maze. The hotel is a labyrinth, with Jack as the monster at its centre, and Wendy and Danny fighting to find their way out through its confusing dimensions.

Or perhaps, since Roy Walker was designing sets and not a real building, he was simply free to construct those sets to best suit Kubrick’s visual intentions. After all, how many viewers were likely to figure out that the parts don’t fit together exactly?

Ryan focuses more on discrepancies and continuity errors. He cites Barry Lyndon as evidence of a brilliant filmmaker utterly bored with what he’s doing (although for me that historical epic is Kubrick’s greatest film – that’s how subjective this all is), and that he decided to use The Shining to playfully mess with the audience’s heads. At one point between two cuts a chair disappears from the background (which Ryan says mocks the conventions of the horror film). At another, a sticker on Danny’s bedroom door disappears between the beginning and end of a scene (pointed out by Cocks, who really reaches for an explanation). Obviously these things are noticeable – particularly if you look at the film over and over again – and Kubrick would have been aware of them during the editing. In other words, he would have chosen to leave them in. But does this really “mean” anything? Anyone who has ever been involved in making a film knows that such errors occur, and often you end up living with them for other reasons.

Kubrick was famous for shooting scenes dozens of times over as he sought the exact performance he wanted. Perhaps going over dozens of takes of every angle, he finally found those perfect moments of performance, but occasionally the art department had slipped up and there was a slight continuity error. Should he sacrifice the performance for consistency of background, or trust that the audience would be emotionally engaged with the drama and not notice? These kinds of errors often only become apparent with multiple viewings, when that initial engagement has been supplanted by a different kind of interest and the eye is free to wander away from the dramatic action to the background.

All of this is rooted in the idea that every detail in the film is consciously placed and filled with a meaning which goes deeper than its design or narrative function. This kind of obsessive exegesis is only possible because of video, which permits endless playback, slowing down, pausing. And it all presupposes that Kubrick intentionally constructed the film not simply as a narrative about the violent implosion of one family, but rather as a system of codes and puzzles sending messages to those who have the ability to see through the surface to its true meaning. It’s almost a relief to hear Kearns say something like “if you look at it for too long it stops making sense.” Late in the film, one of the subjects (possibly Cocks) invokes post-modernism and the idea that meaning has little to do with authorial intention, that deeper meanings creep in due to the social and political context of the text’s making, beyond the author’s conscious awareness – paradoxically negating the central premise underlying the various arguments the interviewees have been making about the film’s meaning, that is, about the subtle genius of Stanley Kubrick.

Ultimately, all the theories seem untethered, pointless – if all those coded references to the Holocaust or the violent colonization of North America were actually present in the film, so what? What does the movie actually have to say about these sweeping historical issues? This obsessive theorizing really says more about these particular viewers than it does about the film itself. According to Kubrick’s long-time assistant Leon Vitali, for instance, the typewriter was actually Kubrick’s own, which happened to be a very sturdy German model, and the lines from The Three Little Pigs were improvised in the moment because Kubrick needed something extra from Jack as he prepared to attack his family, something associated with childhood and domesticity while simultaneously carrying a sense of menace.

And so Room 237 becomes increasingly dissatisfying as it plays out and we realize that there are actually no revelations here, just projections of various people’s pre-existing obsessions, sadly illuminating the need some people have to feel that they alone can see the truth, that they alone have access to hidden secrets which have been buried just for them to discover.

But then something strange happens. Ryan talks about a performance he staged in which The Shining was projected simultaneously forwards and backwards, superimposed over itself, and Ascher shows us portions of the result. It’s remarkable: the images combine in ways which seem truly revelatory, deepening and enriching the psychological content of the narrative. And it’s almost possible to believe that Kubrick, through some almost mystical filmmaking powers, actually did intentionally create this whole other level of meaning in the movie.

I was suddenly reminded of the dangerous works of Max Castle in Theodore Roszak’s novel Flicker, films which through their elaborate layering of hidden imagery embody powerful supernatural forces. The images displayed here at the end of Room 237 actually gave me a chill… For a moment, here was something intriguingly concrete, although it quickly occurred to me that Ascher and Ryan had no doubt chosen to show exactly those moments where the two images coincided most resonantly, and there are over two hours more where things might not work as well. And then I realized that for this to have been intentional on Kubrick’s part he would have had to anticipate someone thinking of projecting the film simultaneously backwards and forwards over itself, and wouldn’t that have meant that he was kind of crazy?

Comments