Edgar G. Ulmer, B-movies, and the art of the low budget

I was a fan of Edgar G. Ulmer before I had any idea who he was. Sometime back in the ’70s, I saw The Black Cat (1934) on television and it became, and remained, my favourite classic Universal horror film. As much as I like the others (particularly the witty work of James Whale), the modernist design and the genuinely perverse atmosphere of Ulmer’s film made a deep and lasting impression. Even after eighty years, it remains disturbing, one of the few horrors from that period before the Production Code gutted the genre which doesn’t look quaint now in retrospect. (Perhaps only Tod Browning’s Freaks, Erle C. Kenton’s Island of Lost Souls [both 1932] and Karl Freund’s Mad Love [1935] can match it.)

Ulmer himself really only entered my consciousness as a filmmaker when I saw his legendary noir Detour (1945) on video sometime in the ’80s. To some degree, this six-day wonder, made with virtually no money for the poverty row company Producers Releasing Corporation, stands as the defining work of the director’s career. With just a couple of sets and a car on a soundstage with rear-projected deserts, Ulmer conjured up one of darkest visions of inexorable fate in American cinema. Detour is a superb example of visual style as meaning; objects looming in the frame imprison and eventually crush the feckless pianist Al Roberts (Tom Neal). The murder-by-phone is the most brilliantly distinctive moment in the entire noir canon, and is there any other performance in American film which embodies the horror of an inescapable fate more magnificently than Anne Savage’s monstrous femme fatale?

With the advent of DVD, Ulmer’s works began to emerge from obscurity (many of them thanks to David Kalat’s All Day Entertainment). It became apparent that Detour wasn’t some strange anomaly, and that Ulmer himself wasn’t some pathetic victim of an industry which wouldn’t give him a chance. IMDb lists over fifty titles in just over thirty years and the range of genres is impressive. I have nineteen Ulmer titles in my collection – among them, in addition to The Black Cat and Detour, the costume epic The Pirates of Capri (1949); Carnegie Hall (1947), his odd but affectionate ode to classical music performance; Strange Illusion (1945), a noir-ish updating of Hamlet; the period psychological drama Strange Woman (1946, with one of Hedy Lamarr’s finest performances); the psychological horror film Bluebeard (1944, with one of John Carradine’s finest performances); the atmospheric alien invasion story The Man From Planet X (1951), which uses a soundstage and a fog machine to conjure its remote Scottish location; and the ultra-low-budget Moon Over Harlem (1939), one of Ulmer’s “ethnic” features, this one featuring an all-black cast giving a glimpse of African-American life in New York in the ’30s, accompanied by a jazz score. (I recently bought his four Yiddish features, also from the late ’30s, from the National Center for Jewish Film at Brandeis University, but have only had time to watch the first, Green Fields [1937], a remarkable accomplishment given that it was made for virtually no money at all; Ulmer’s story of the production, recounted in the extensive interview he gave Peter Bogdanovich in 1970, is fascinating.)

Having seen all these, I thought I had become reasonably familiar with Ulmer’s work, but then the BFI released Menschen am Sonntag (People On Sunday, 1930) on DVD in 2005 (more recently released on Blu-ray by Criterion in 2011). This startling work, co-directed by Robert Siodmak and scripted by Billy Wilder, combines the city film of Dziga Vertov and Walter Ruttmann with the techniques of neo-realism avant la lettre, using non-professionals to illuminate the lives of ordinary Berliners towards the end of the Weimar Republic. The film was shot by future Oscar-winner Eugen Schufftan, who like Ulmer ended up in Hollywood but in a more prominent position (though he worked with Ulmer on a number of films, uncredited).

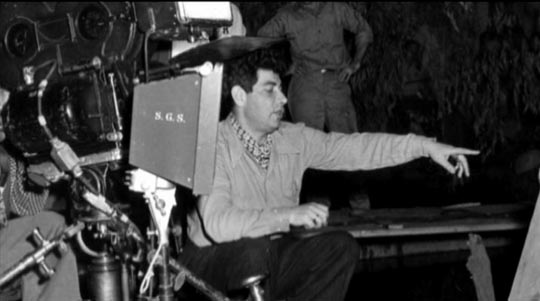

Throughout the ’20s, Ulmer had been very active in the German film industry, working with people like Fritz Lang and F.W. Murnau as a designer and art director. He was involved in solving the technical issues which enabled Murnau to develop the fluid camera technique of Der Letzte Mann (The Last Laugh, 1924), and this ability to facilitate visual storytelling served him throughout his low-budget career in Hollywood. No matter how little time and money he had, he always gave his films a visual distinction – using careful compositions combining resonant framing and a moving camera – which almost invariably improved on the often inadequate scripts he was handed by producers who simply wanted product to fill their release schedules. Which is not to say that Ulmer felt himself to be superior to the material he worked with; he was sincerely committed to making the most of what he was given.

There were occasions when Ulmer found himself with a more then adequate budget and not surprisingly the additional money shows up clearly on screen … but these bigger films are given no more careful attention than the poverty row quickies; he makes the best use of the resources at hand regardless of the budget. In even the most impoverished of his films, you can see the creative intelligence at work, the careful attention to psychological as well as visual detail, so it’s interesting to see him work on a larger scale in Ruthless, the third of four somewhat more prestigious films he made in the late ’40s (following Strange Woman and Carnegie Hall and just before The Pirates of Capri).

Ruthless (1948)

Although Ulmer may seem like an odd candidate for Blu-ray release, Olive Films’ choice of Ruthless is appropriate because, unlike the cramped world of Detour, this film unfolds on large opulent sets with, if not a cast of thousands, then certainly enough background players to populate its wealthy social milieu. More than one critic has evoked the name of Citizen Kane when talking about Ruthless and there are definite similarities between the two films: both deal with men whose childhood traumas drive them relentlessly to seek power and wealth; both use a flashback structure to paint complex portraits of their protagonists; and both make striking use of deep focus photography to emphasize the conflict between the human scale of the characters and the grandiose rooms they try and ultimately fail to inhabit. (Interestingly, Ruthless was shot by Bert Glennon who worked extensively with John Ford, as had Gregg Toland, who shot Kane for Orson Welles.)

We first meet Horace Vendig (Zachary Scott) at a gala in his mansion where he’s turning over the property and a lot of money to the cause of world peace. This act of philanthropy is witnessed by his old, estranged childhood friend Vic Lambdin (Louis Hayward), who views it with some cynicism. Vic and his companion Mallory Flagg (Diana Lynn) meet Vendig in private and the rich man is shocked to discover that Mallory is the spitting image of their childhood friend Martha Burnside (also Lynn) who was set to marry Vic until Vendig swept her away. This established a pattern for the rest of his life; Vendig is driven to take what other people have – in both finance and relationships – only to discard people once he’s possessed them or taken all the profit he can from them. He leaves a trail of broken victims which we see in a series of extended flashbacks which interrupt the reunion. Finally, Vendig even attempts to take Mallory from Vic, only to meet his match at last … and, in the film’s least satisfactory moment, he also meets his doom at the moment of rejection.

Here Ulmer, so used to creating the illusion of sets from a wall or two and a handful of objects, sweeps his camera through ballrooms and boardrooms, capturing a sense of wealth as space which the characters strive to fill with their egos. The link between damaged psyches and the obsessive pursuit of money is embodied in the film’s visual design, the style becoming the theme. Ulmer himself called the film a morality tale about the American obsession with money, and here decor defines character either through alignment (Vendig, Buck Mansfield [Sydney Greenstreet] and his wife Christa [Lucille Bremer], both of whom are destroyed by Vendig) or opposition (Vic and Mallory, who resist Vendig’s power and render it impotent by their refusal to bow to his influence).

In the lengthy interview Ulmer gave Peter Bogdanovich in 1970, he mentions that Ruthless was actually written by Alvah Bessie, one of the Hollywood Ten who went to prison for defying the House Un-American Activities Committee in the late ’40s. The credited writers (S.K. Lauren and Gordon Khan) were a front. Ulmer also mentions that the intended ferocity of the film’s attack on capitalism was somewhat muted when the studio (Eagle-Lion) made several substantial cuts before release (something he didn’t experience on his poverty row productions, which is one of the reasons he was happy working at the bottom of the budget barrel). But even if that was the case, the film paints an undeniably bleak picture of the power of money to deform people. And yet, we never lose sight of the damaged person Vendig is, and no matter how destructive he becomes he remains strangely sympathetic, as much a victim of the American capitalist dream as the people he ruins along the way.

Comments