Recent Documentary Viewing, Part 2

In the past several years, I’ve discovered three British documentary filmmakers who immediately became favourites. While their personalities and styles vary widely, all share what might be called a traditional, observational approach. They find situations which interest them and then carefully observe the people involved … all three make films which are about discovering something in the world rather than presenting an argument or particular point of view; all encourage the viewer’s interest in the variety of social life.

Molly Dineen, like the legendary Frederick Wiseman, has a particular interest in the ways institutions operate and in the behaviour of people in those institutions: the army, the House of Lords, the London zoo (her work is available in three excellent DVD sets from the BFI). Marc Isaacs’ approach is more microscopic than macroscopic, focused closely on the small details of individual lives mostly in and around London. Kim Longinotto comes somewhere between these two positions, intensely focused on portraits of individuals embedded in social situations in radically different societies.

Kim Longinotto

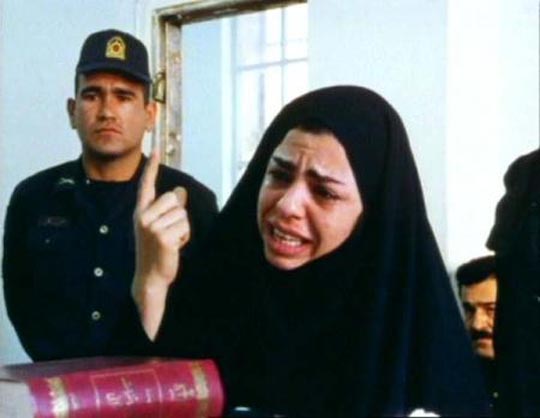

I first came across Kim Longinotto in 2009 on a region 2 disk from Second Run containing a pair of films she’d made in Iran (co-directed with Ziba Mir-Hosseini), Divorce Iranian Style (1997) and Runaway (2001), both of which embodied the filmmaker’s aim to examine the ways in which women carve out a place for themselves within societies which generally devalue and oppress them. Longinotto’s work is too calm and attentive to detail to become a didactic attack on patriarchy, yet her films are constantly surprising and often revelatory in ways which a more overtly political approach would fail to be.

I recently saw three more of her documentaries: Gaea Girls (2000) and Shinjuku Boys (1995), both co-directed with Jano Williams (Second Run, region 2), and Sisters In Law (2005), co-directed with Florence Ayisi (Drakes Avenue, region 2). All three introduce the viewer to previously unknown situations which are likely to alter the way we think of other cultures.

The Japanese double-bill presents two radically different ways in which Japanese women have chosen to stand against traditional definitions of their roles in society. Gaea Girls observes a training school for women wrestlers, following several of the students as they submit to a gruelling regime designed to toughen them both physically and mentally. It’s a harsh, even brutal film; the women have to crush every vestige of female “weakness” in themselves, learn how to endure pain and keep coming back for more.

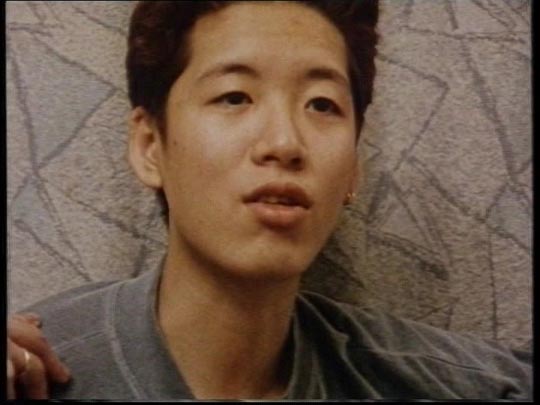

Shinjuku Boys is also about attempting to erase the feminine in order to escape societal constraints, but in this case Longinotto is observing the subculture of onnabe, women who live as men, serving as hosts in Shinjuku bars who offer their female clients a gentler, more desirable kind of masculinity, a non-threatening ideal. Some of the women merely dress as men, but others are undergoing medical transformations. The film depicts their interactions with customers, but also their private lives and relationships, cut loose from pre-defined roles.

Sisters In Law was the second film Longinotto made in Africa. Shot in the small village of Kumba, Cameroon, it follows the work of Vera Ngassa and Beatrice Ntuba, a prosecutor and court president respectively. The cases dealt with all revolve around family law – divorce, spousal abuse, child abuse – and all are freighted with deeply ingrained social attitudes which give men dominance over women and children. Some of the brutality we see is shocking, but the fierce determination of the two women to shift those attitudes also produces a degree of humour, with men in the court squirming under Beatrice’s unflinching lectures.

Despite the sometimes grim situations depicted in Longinotto’s films, their tone is always optimistic; triumphs may be small and incremental, but her subject is resilience and the possibility of change.

Marc Isaacs

Marc Isaacs tends to stay closer to home than Longinotto, but he shares her fascination with the details of lives often little observed. I fell in love with his work when I first saw his debut, Lift (2001), on a Second Run region 2 DVD, which also included Travellers (2002) and Calais: The Last Border (2003). Lift is brilliant in its simplicity: Isaacs sits for weeks with his camera in the elevator of a highrise, gradually getting to know the residents through their responses to his presence, while observing the shifts in their behaviour and attitudes as they get used to him being there. Travellers enlarges his canvas while maintaining a similar approach, as he rides the same commuter train over a long period, getting to know his fellow passengers and gradually revealing their personal stories.

Isaacs has a seemingly bottomless curiosity about other people and there’s a sensitivity and generosity in his work which elicits empathy even for people you might be inclined to shy away from – the wealthy businessmen in Men of the City (2009), the racist residents of an area of London with a large immigrant population in All White In Barking (2007).

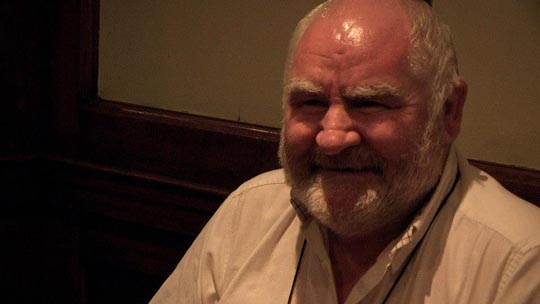

Immigration, or perhaps more precisely dislocation, is the subject of The Road: A Story of Life and Death (2012, Drakes Avenue, region 2), in which he sets out to get to know various people in his own area of London. A young Irish woman looking for a better life; an elderly Irish man who has lived and worked in exile for most of his life and is now lost in alcoholism. A widowed survivor of the Holocaust, now in her 90s and happy to be free of the husband she didn’t much like; a man from Kashmir, working at a big hotel, as he waits to be able to bring his wife to England. A retired German air hostess who lives with her estranged husband; a Burmese Buddhist who decides to abandon his wife back home and become a monk.

Isaacs lets these people talk about their lives, their pasts, their hopes and fears, capturing the flow of life in a big city which in many ways never becomes home. In a world where many people are unable or don’t want to remain where they’re from, this experience of transience and dislocation reflects a widespread existential condition, and the film reminds us of just how fragile life and a sense of identity can be.

*

Having said that, I must admit that I was troubled by comments made about The Road by Jerry Whyte at Cine Outsider, in which he goes into some detail about the ways in which, through dramatic construction and the omission of important details, Isaacs misleads the audience about the people he films. If accurate, Whyte’s assertions indicate far more than a simple selectivity with regard to details; he accuses Isaacs of distortions and falsifications which actually do a disservice to the lives of the people portrayed in the film, which seems really unfortunate because those people nonetheless remain fascinating characters who would have engaged our interest even if honestly portrayed.

Comments