The Fabulous World of Karel Zeman

One of the best things about Glenn Erickson’s DVD Savant column over at DVD Talk is his habit of posting, along with his knowledgeable reviews, interesting and useful links. A little while back, he alerted his readers to the website of a museum in the Czech Republic devoted to the work of filmmaker and animator Karel Zeman. Although there’s no chance of me visiting the museum itself, I was excited to see that they offer DVDs of three of Zeman’s features – Journey to the Beginning of Time, The Fabulous World of Jules Verne, and The Fabulous Baron Munchausen. Since they accept Paypal, I ordered all three for the insanely low price (including shipping) of $35 and they arrived four weeks later.

I knew very little about Zeman, although I’d first read about him some 40 years ago. In fact, a still from Jules Verne appears as the first image in John Baxter’s Science Fiction in the Cinema (1970), one of the key books in my early education in film, which introduced me to many titles long before I had a chance to see them. Over the years, I encountered other images, again mostly from Jules Verne, which appeared to be his best-known work in the West. These images were intriguing, but I found it difficult to imagine how the film would actually work – they looked like woodcuts from an old book, which is exactly what Zeman intended.

Zeman was a remarkable filmmaker who should be far better known than he is. Born in 1910, just a decade and a half after the birth of cinema, he arrived at his eventual career by way of advertising and window display design. Trapped in Czechoslovakia during the Nazi occupation, he came to the attention of filmmaker Elmar Klos (eventually co-director with Jan Kadar of the 1965 masterpiece The Shop On Main Street) who lured him away in 1943 from teaching at Bata’s window-dressing school to work at an animation studio, where he became director of the stop-motion department in 1945. There Zeman embarked on a career of experimentation with animation techniques, initially in shorts and a 1952 feature which combined puppets and two-dimensional animation, but then starting in 1955 in a series of six features which combined animation with live action.

The disks from the Muzeum Karla Zemana (nicely produced in English-friendly versions, with attractively colourful packaging) contain the first three of these films, along with a handful of very brief featurettes giving glimpses of how the work was done.

Journey to the Beginning of Time (1955)

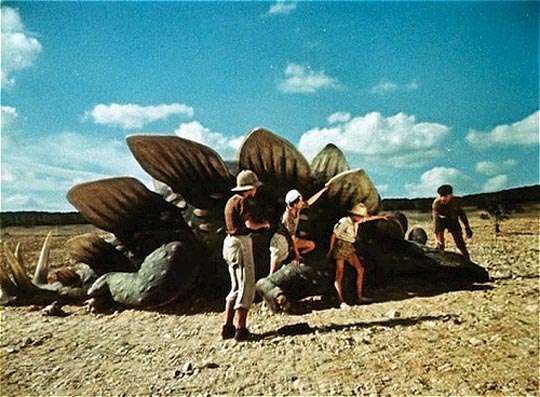

The first film, Journey to the Beginning of Time, is a terrific kids’ adventure which contains its educational purpose within the story of four boys who set out one summer to paddle upstream on a river which turns out to be a path back through time, eventually to the origins of life itself. Influenced by Jules Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth and the paintings of Zdenek Burian (I still have two large volumes of colour plates of his work that I bought at Expo 67 in Montreal), the film substitutes a sense of wonder and the excitement of discovery for more conventional dramatic elements.

The boys travel back in time, past the origins of the human species, through the various major ages of paleontology, where they encounter evolution in reverse. Zeman’s stop-motion animated mammoths and dinosaurs are as impressive as Ray Harryhausen’s in One Million Years BC (1966), but they’re used for different purposes. This film is intended to teach kids about the theory of evolution, going back to the primordial ocean from which all life emerged, and as such it stirs a sense of excitement about science rather than aiming for the horror of monsters more typical of western movies.

The Fabulous World of Jules Verne (1958)

The next film is something completely different, though the sense of wonder is, if anything, exponentially increased. It’s almost impossible to convey in words what Zeman did in The Fabulous World of Jules Verne – although I’d read about the film on and off for four decades, I was completely unprepared for the experience of watching it. I’ve never seen anything like it before and imagine that it remains totally unique. The story itself is fairly similar to Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954); Count Artigas, a Captain Nemo-like figure, kidnaps Professor Roch, a scientist who is working on a powerful new source of energy (i.e. atomic), in order to obtain the secret which will enable him to subdue the war-prone human race. The professor’s assistant, Simon Hart, sets out to stop these plans, tracking Artigas to a remote volcanic island where the powerful new weapon is being built by Roch, whose scientific determination blinds him to the consequences of his work.

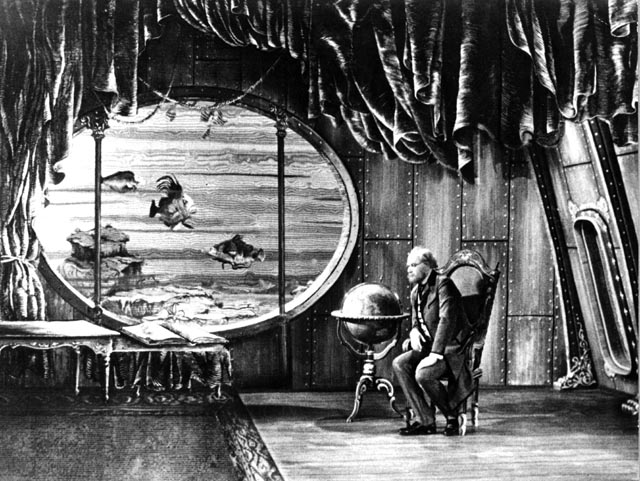

But it’s not the story (as entertaining as it is) which gives the film its unique qualities. Zeman set out to emulate the 19th Century woodcut illustrations of Verne’s novels, shooting in black-and-white, and painting every set with patterns of cross-hatched lines which give the impression of those illustrations come to life. The live action is combined with drawn animation, stop motion, models and pretty much every trick which has been discovered since Melies started creating his fantasies in the 1890s. I watched this film with a childlike sense of wonder, carried by its fairly simple story of adventure, but enthralled by the seemingly impossible life instilled in its images. The underwater sequences in particular are breathtaking with their elaborate layering of painted backgrounds, foreground mattes, working model submarines and strange sea creatures, all appearing to be actually under water. As always with the best kind of special effects, it’s the resulting effect itself which matters and perhaps only afterwards do we pause to try to figure out how the heck it was done.

The Fabulous Baron Munchausen (Baron Prasil, 1962)

If Jules Verne harks back to a pre-cinematic style of visual storytelling – and in the process redefines just what “cinematic” might mean – Zeman’s next feature attempts to create a bridge between the present (that is, the 1960s) and the very origins of cinema, linking the grand new technological age of the space race to the limitless potential offered by the first machines that made images appear to move. It’s probably impossible for anybody who wasn’t around at the time (and perhaps of a certain age) to understand just how much the first moon landing altered our perception of the world. Reality had caught up with fantasy and in the process, to some degree, seemed poised to end fantasy altogether. In our living rooms, we watched as two men walked about on the surface of the moon, something we had read about in science fiction and seen portrayed in movies as a future just beyond tomorrow. We had dreamed of reaching that future and all its possibilities, and now here it was … but, paradoxically, it abruptly lost its sense of magic. The real thing seemed strangely prosaic, a technocratic event accomplished in the emotionless tones of engineering rather than the poetry of imagination.

Karel Zeman seems to have anticipated this strange dichotomy seven years before Neil Armstrong took that first step. His adaptation of the story of Baron Munchausen – in Czech, renamed Baron Prasil (1962) – begins (like Ray Harryhausen’s First Men In the Moon two years later) with an astronaut landing on our near neighbour only to discover signs of the past. But unlike that later adaptation of Wells, here it’s not an earlier technological past, but rather a literary, imaginative past. The astronaut finds himself in the company of the characters from Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon along with Baron Munchausen, the group inviting him to dinner where they treat him with condescension in the belief that he’s a native inhabitant of the moon.

The Baron decides to introduce this supposedly alien character to Earth and flies him there in a ship powered by winged horses, landing in 18th Century Turkey where the spaceman not only commits social faux pas because customs of the time are completely alien to him, but more dangerously falls in love with a Princess imprisoned by the Sultan, triggering battles and adventures in which the astronaut becomes as much of an outsized figure as the Baron himself.

All of this is rendered visually in terms of the kinds of camera tricks and sets which Melies used to create his fantasies, drawing the science and technology of the ’60s back into a lively realm of imagination where once again anything becomes possible.

Zeman was a unique talent who, in a handful of features, pushed the visual and expressive possibilities of film into new areas by returning to the past and, to some degree, forgotten modes of expression. As I said above: he deserves to be far better known in the West than he is.

Comments

I just found the fabulous world. It is mesmerizing. Has anyone tried to duplicate this work of art?