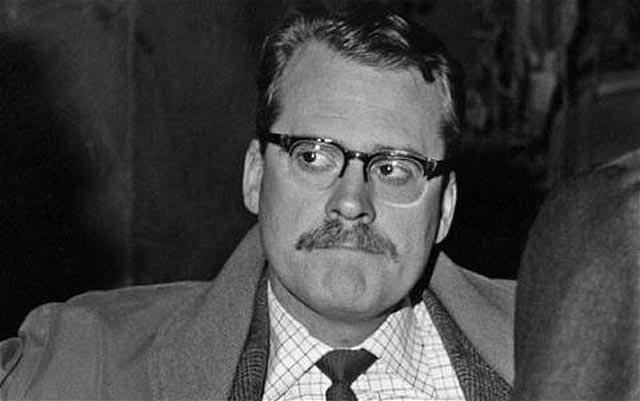

Anthony Hinds 1922-2013

I just learned that Anthony Hinds died three weeks ago, aged 91. Although perhaps not a household name, Hinds was one of the most influential post-war producers not just in British film, but in world cinema in general. And this despite the fact that he apparently wasn’t enamoured of the business; a quiet man, he disliked conflict and the rough politics of making movies.

Hinds’ father William was co-founder in 1934, with Enrique Carreras, of a small production company called Hammer Films. For a few years it produced quota quickies before becoming dormant in the late ’30s. When a decision was made to revive the company after the war, Hinds was delegated by his father to run it and Hammer became a fairly prolific producer of B-movies, mostly thrillers and mysteries.

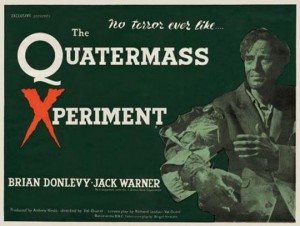

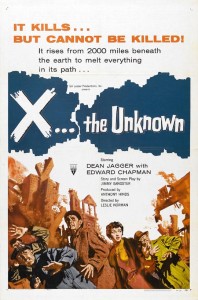

Then in the mid-’50s, Hinds made the fateful decision to produce a feature adaptation of Nigel Kneale’s hugely popular BBC science fiction serial The Quatermass Experiment (directed by Val Guest and retitled The Quatermass Xperiment to emphasize a provocative embrace of the British Board of Film Censors’ most restrictive X rating). The film was a big hit, not just in England but also in export to the States as The Creeping Unknown. The transformation wrought by this production didn’t take hold immediately, however; Hammer continued to produce its mysteries and thrillers for another year or so, revisiting just once the lucrative SF genre with what was essentially an unauthorized sequel to the Quatermass film, X the Unknown (Leslie Norman, 1956). Although merely an enjoyable minor work, the real significance of X the Unknown was that it brought a young writer named Jimmy Sangster to Hinds’ attention.

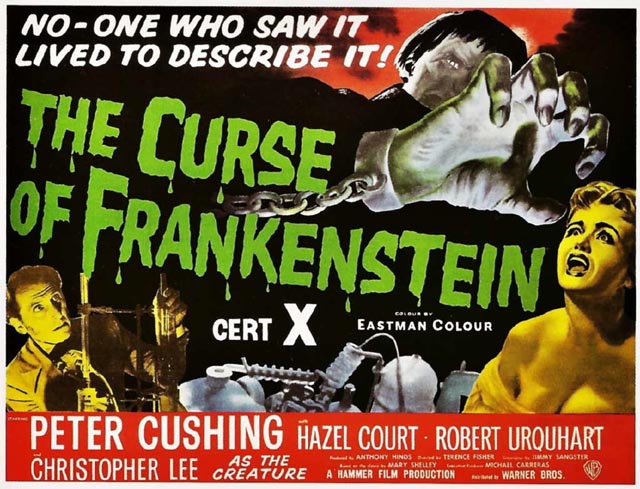

Whether he was aware of the full implications of his decision or not, Hinds asked Sangster to write a script based on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein – but not as a traditional tasteful literary adaptation; he wanted sex and violence, as much as the slightly loosened post-war censorship would allow. The result was The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), the film which changed everything. Despite its low budget, the film was shot in colour, giving director Terence Fisher an opportunity to break out of his well-established niche as an efficient maker of sometimes emotionally charged B movies, with an occasional gem like So Long at the Fair (1950) to his credit.

What’s remarkable about The Curse of Frankenstein is that something brand new seems to have flowered without any prior notice. Hammer is now known for its flamboyant, colourful period horrors, but before this film there was no real indication of such a tendency. It was one of those almost mystical confluences which result in something entirely new: with Hinds producing, Sangster writing, Fisher directing and, crucially, Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee starring, the film marks a sharp dividing line between what was and what was coming to be. Nothing would be the same afterwards, and the film’s influence extended to Europe and the States. Would Mario Bava have had quite the career he did if this film had never been made? Would Roger Corman have managed to persuade AIP to finance his great, colourful Poe adaptations?

This time Hinds knew what he had; he quickly reassembled the team for a follow-up adaptation of Dracula, with Sangster’s script doing an excellent job of wrestling Stoker’s unwieldy novel into a fast-paced coherent narrative which consolidated Lee’s and Cushing’s status as the Hammer stars and Fisher as director of choice for what would become the studio’s signature Gothic horrors.

This time Hinds knew what he had; he quickly reassembled the team for a follow-up adaptation of Dracula, with Sangster’s script doing an excellent job of wrestling Stoker’s unwieldy novel into a fast-paced coherent narrative which consolidated Lee’s and Cushing’s status as the Hammer stars and Fisher as director of choice for what would become the studio’s signature Gothic horrors.

But beyond securing the company’s fortunes (at least for the next decade), these productions changed the face of British film. Although greeted with howls of protest from critics and more conservative elements of society, people who viewed them as tasteless and offensive, they were hugely popular with audiences (and frustrating for a kid like me who wasn’t allowed in to see them because of the X rating) and set in motion the gradual loosening of the British censors’ grip on popular movies, a process which eventually led to the release of films like A Clockwork Orange, Straw Dogs and The Devils (yes, such films were often still clipped by the censors, but now the gates were open for filmmakers to deal with virtually any subject matter, and confrontational and potentially offensive material was now permissible on British screens).

Anthony Hinds, always a reluctant figure in the industry, finally quit in 1969 and went on to other pursuits. Hammer, which had continued to combine science fiction and thrillers with its period horrors, was already beginning its decline by then as it was being left behind by the world it had helped to create. There were still a few good films to come, but without the pressures of censorship to push against, many of the company’s productions descended into tired titillation and embarrassing attempts to mix the now over-worked Gothic with trendy ’60s attitudes.

Anthony Hinds, always a reluctant figure in the industry, finally quit in 1969 and went on to other pursuits. Hammer, which had continued to combine science fiction and thrillers with its period horrors, was already beginning its decline by then as it was being left behind by the world it had helped to create. There were still a few good films to come, but without the pressures of censorship to push against, many of the company’s productions descended into tired titillation and embarrassing attempts to mix the now over-worked Gothic with trendy ’60s attitudes.

But even as a newly revived Hammer Films tries to re-establish itself as a significant producer of horror (the promising Wake Wood, the dire remake of Let the Right One In, best of all The Woman In Black), it’s still the ground-breaking films of that decade between The Curse of Frankenstein and The Devil Rides Out (1968) which define the company for fans. And those fans remain passionate (look at the furious on-line debates about the restorations being done for new Blu-Ray releases). Although Anthony Hinds ended his involvement in the movies more than thirty years ago (having written a number of scripts throughout the ’70s under his pseudonym John Elder), hopefully he was gratified to know that the work he did five and six decades ago remains as vital today as it was when it was new and changing the cultural landscape.

Anthony Hinds: 19 September, 1932, to 30 September, 2013.

Comments