October 30, 1938: When Welles Unleashed Wells

Although radio broadcasting arrived more than two decades after the birth of cinema – and movies were the dominant form of entertainment in North America for the first half of the century – radio was in some ways a far more important and influential medium. Looking back from the perspective of our wired (and wireless) world, it’s difficult to comprehend just what a powerful change the new medium brought about as it took hold in the 1920s. People then still lived within their own communities, their lives circumscribed by the limits of geography, news from afar arriving days or even weeks after the event in the form of print reports.

While movies were an escape from daily life, radio was rooted in it. It shrank distances and created connections where none had previously existed. Certainly it was a major source of entertainment, of music, drama and comedy, and it brought these things directly into people’s homes, absorbed into the rhythms of life instead of being something sought outside. But more importantly, it introduced an immediacy to reports of what was happening in the world. No longer could people comfortably exist in isolation; the world suddenly shrank and everyone became aware of larger forces in the face of which they found themselves relatively powerless. When the world seemingly collapsed in 1929 and the Great Depression took hold, radio reported every blow. But at the same time, it also provided a sense of shared struggle – the entire nation was in the same boat and, after 1932, the soothing voice of FDR offered hope and consolation in his weekly fireside chats over the radio.

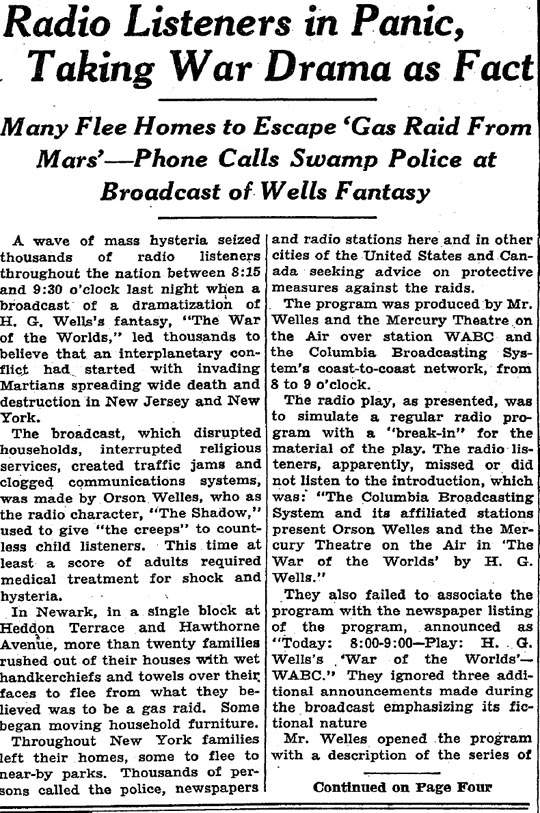

For millions of people, radio had become a powerful connection with the world, a source of information and knowledge which they implicitly trusted. Naturally, it would take a brash young genius to see how that trust could be exploited for maximum dramatic impact and on October 30, 1938, 23-year-old theatre wunderkind Orson Welles led his Mercury Theater on the Air in a one-hour adaptation of H.G. Wells’ 1898 novel The War of the Worlds.

The famous pre-Halloween broadcast marked what may have been the first full-scale earthquake to hit the mass media of the 20th Century. The story has been examined in countless articles and books, and even a made-for-TV movie (The Night That Panicked America, 1975), and now to mark the 75th anniversary American Experience offers a one-hour documentary (debuting both on PBS and DVD/Blu-ray on October 29) which delves into not only what happened but why and how. From our supposedly media-savvy perspective we tend to feel a certain superiority to all the gullible people who heard the broadcast, believed it was really happening, and panicked – there were even reports of heart attacks and attempted suicides. (Although given how easily swayed many people are by hyper-ventilating cable news coverage of events today, we don’t seem to have come very far after all.)

Using interviews with historians Susan Douglas and T.J. Jackson Lears, media historian Paul Heyer, writers Eric Rabkin and Robert Crossley, journalist David Ropeik, filmmaker and Welles protege Peter Bogdanovich, and Welles’ daughter Chris Welles Feder, the documentary quickly fills in the context of the broadcast. Coming a decade after the onset of the Depression, a year-and-a-half after perhaps the most powerful media event to date – the Hindenberg disaster of May 6, 1937 – and just one month after Neville Chamberlain’s capitulation to Hitler in Munich, the Mercury broadcast went out to an audience already highly stressed and fearful of a new war. But none of this would have mattered if Welles hadn’t made a radical creative decision just days before the broadcast.

Having commissioned a script from writer Howard Koch, Welles didn’t actually see it until the middle of the week before the scheduled live Sunday air date and he found it extremely dull. Casting around for a solution, he came up with the idea of reshaping it as a live broadcast of events as they happened, framing the invasion as an interruption of regularly scheduled programming. Once he had this idea, everything fell into place and the script became a breathless account of catastrophic on-going events. (Frank Readick, who played the show’s reporter character, Carl Phillips, reportedly listened to a recording of the Hindenberg explosion over and over again to get the tone just right, and when the play’s report of the first Martian attack is presented beside that Hindenberg broadcast it sounds virtually identical.)

Although the play was advertised as part of the network schedule and announced at the beginning as a Mercury production, many people scanning their radio dials came across it in progress and had no way of telling that it was merely a drama. And so anxiety was easily triggered; and pre-existing fears caused people to hear not necessarily what was actually being broadcast but rather what they were expecting to hear – that this was a German invasion and the new war was beginning. Naturally, many didn’t stick around to hear more … they called friends and relatives with warnings, they called the police, they jumped in their cars and headed for what they hoped was safety …

Very early in the broadcast, the CBS switchboard began to be flooded with calls from concerned listeners and the network realized that they had a problem on their hands. They sent word to the studio insisting that a station identification be inserted immediately, with an assurance that this was merely a drama. Welles, also realizing that he was creating an event, held off as long as he could, finally allowing the station break at around the half-hour mark. But by then the panic was in full sway and many of the listeners who needed the reassurance had already stopped listening and started running.

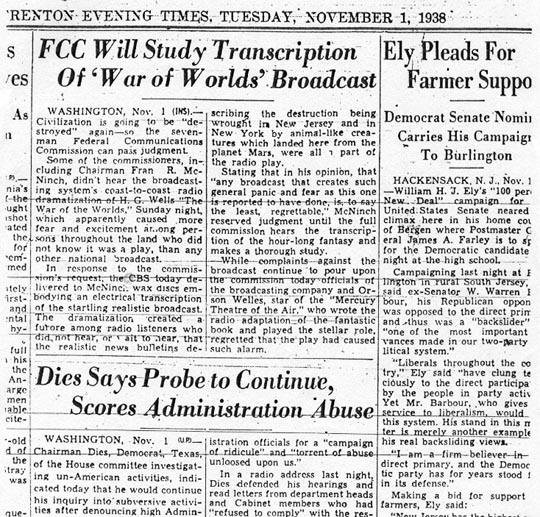

In the aftermath, with calls for enquiries and some people demanding criminal charges against Welles and the network, it became apparent that the actor-director had managed to shatter what in retrospect looks like a naive trust in the integrity of the media. While some saw it as exposing the gullibility of the public, others realized that it was a chilling demonstration of the power of propaganda such as the Nazis were pouring out in Europe at the time to pave the way for the coming war.

Welles, in one of the finest performances of his career, appeared at a press conference the following day to express his shock at the reaction to his trifling play and to apologize for the distress he had caused – all the while basking in his vastly expanded fame (and notoriety), which would lead directly to the remarkable Hollywood contract which would result in his groundbreaking film Citizen Kane.

The American Experience documentary, produced and directed by Cathleen O’Connell, presents a clear and vivid account of these events, managing to make the panicked audience’s reaction comprehensible, without a trace of condescending hindsight. But, perhaps without conscious irony, this account of the mass media’s first full-blown fake-umentary, incorporates a collection of interviews with people who were caught up in that panic, ordinary Americans recounting their own fear and anger. Based on thousands of letters sent to Welles and CBS after the broadcast, these “recreations” are shown in black-and-white with the look of ’50s video recordings to indicate their age and authenticity … although they’re actually actors performing a script based on those letters. Directed by Josh Seftel, these clips edge towards caricature and instead of providing another layer of immediacy become an annoyingly artificial device where perhaps simple readings from the original letters might have had more impact.

Although the official DVD release reportedly contains several extras – a making-of, a featurette about those letters to Welles, and some outtakes – the disk provided for review contained only the program itself and so we can’t comment on those special features. But the show itself is well-worth a look and at just one hour feels almost too short to do the subject full justice.

Comments

A few days ago on CBC radio (perhaps The Current) a historian claimed the reaction/panic to Welles’ broadcast had been greatly exaggerated. It was suggested the panic was, in fact, largely itself a fabrication by Newspapers attempting to discredit Radio, which Newspapers considered a serious new threat to their existence.

Perhaps the panic has become accepted as fact at least in part because we like to think how naïve people were ‘back then’.

I feel this is supported by the staged clips performed by actors in The American Experience.

Perhaps for every panicked reaction there were 50 or 100 people smirking and/or rolling their eyes…but that wouldn’t satisfy our view of the American experience, would it.

What do you think?

Hi Grant

I didn’t hear the interview, so can’t say anything about the data that historian may have presented. But whatever the scale of the event, I think it’s undeniable that the broadcast had sufficient impact to shake the network and require some very fast damage control. And whether or not the print media blew it out of proportion for their own ends, the whole thing did serve to shake public confidence in the trustworthiness of the media in general … people tend to resent being fooled and will either strike out angrily against whoever duped them, or actually embrace the lies and make them “true” in order not to feel like idiots (the way so many, all these years later, cling to the lies that led to the Iraq invasion despite all the evidence that’s since come out – and in fact came out very quickly – to expose them; there are many Americans who still believe Saddam was behind 9/11, that the hijackers entered the US illegally from Canada, that all those weapons of mass destruction were really there, etc) … so personally, I think the War of the Worlds thing was a real event, though we may argue about the scale of it.

I just read an article in the weekend paper by two academics (Jefferson Pooley and Michael Socolow) making the argument you mention, Grant, and though there’s a slightly smug revisionist tone to it, they do seem to make a convincing case. But as newspaperman Maxwell Scott says in John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”