Art of the Comic Strip: Dear Mr. Watterson

At some time in the process of our transformation into “consumers” – that is, after the fundamental shift in our relationship with the world around us where exchange value superseded all other considerations – a strange confusion arose between artists and the art they created. We somehow came to believe that if we appreciated the art we automatically had a relationship with the artist, that the connection was personal, that artists must acknowledge our appreciation by some strange reciprocal recognition of us. This process eventually became codified in the idea of celebrity. When we worship, we feel that these objects of our adoration owe us something in return. We feel that there’s something wrong with an artist who wants to remain private, who doesn’t appear to want us to have access to their lives as well as their art. People like Stanley Kubrick and (perhaps the prime exemplar of the condition) J.D. Salinger are virtually considered to have some kind of psychological defect because they show no particular interest in our interest in them.

Although first-time documentary filmmaker Joel Allen Schroeder quickly asserts that his interest in Dear Mr. Watterson is not with the elusive creator of the legendary comic strip Calvin and Hobbes, but with the strip itself and the impact it has had on his and others’ lives, the invisibility of Bill Watterson hangs over the project and as a constant subtext prods that strange mixture of admiration and puzzlement which arises from the artist’s withholding of himself from his fans. The title itself suggests an underlying desire that the film will reach and be appreciated by Watterson.

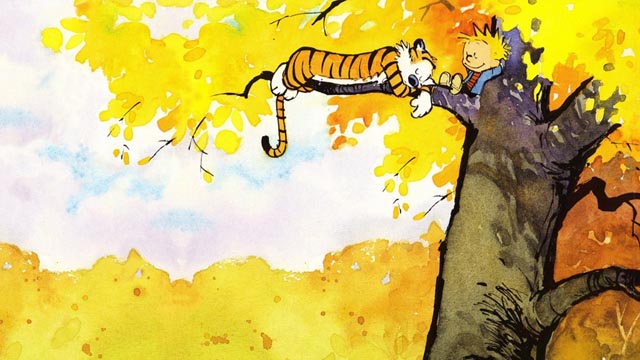

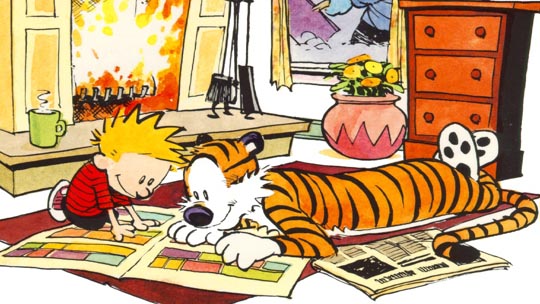

Dear Mr. Watterson is most definitely the work of an admiring fan. Schroeder encountered the comic, to the best of his recollection, somewhere around the mid-point of its ten year run from 1985 to 1995 and, like many kids, found a reflection of himself in the imaginative, adventurous little kid Calvin – or perhaps a reflection of what he would like to be. This boy’s imaginative world seems to have no limits, an endless progression of adventures with his stuffed tiger Hobbes which transform the boundaries of his small-town life into a place full of aliens, monsters and heroic deeds, with Hobbes offering wry commentary on his human pal’s excesses.

Schroeder has sought out fellow fans and admirers as well as a remarkable roster of more than a dozen prominent comic strip artists who talk at length about Watterson’s work – the remarkable qualities of the drawing and writing which, many assert, mark Calvin and Hobbes as perhaps the last great comic strip in a tradition which stretches back a century and includes the innovative work of artists like Winsor McCay (Little Nemo in Slumberland) and George Herriman (Krazy Kat), who introduced sophisticated narrative concepts and surreal visual touches to the readers of daily newspapers. Watterson’s work too expresses a complex view of life within a seemingly simple form.

As Schroeder’s interviewees make clear, this kind of work existed in a problematic arena; the fact that it made its appearance in daily newspapers, the most disposable print medium of all, seemed to suggest that the comics themselves were trivial and disposable. And yet, the fact that they appeared in newspapers meant that they reached a vast audience every day, far beyond the scope of “high” art. At its height, Calvin and Hobbes ran in 2400 papers worldwide; even if only a percentage of readers took the time to look at the strip, that still amounts to tens of millions of readers every day. The pressure on someone like Watterson, who preferred a quiet life and complete control over his own creation, must have been extraordinary.

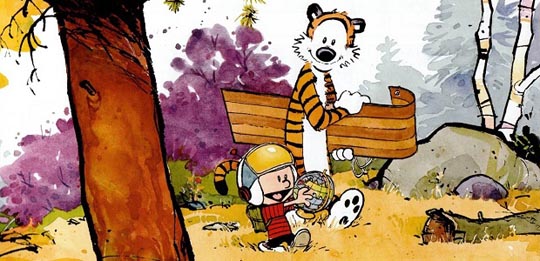

That desire for control drove the artist to do two things which went against the grain of the business he was in. He decided that the strip would have a finite life – ten years – and gave it a poignant conclusion in which Calvin and his pal Hobbes headed off into the empty space of a new page seeking further adventures which their readers would no longer be able to share. And, perhaps most radically, he refused all efforts to merchandise the strip; he and his publishers missed out on millions of extra dollars because there were no movies, no TV shows, no stuffed toys, no cups, no lunch boxes … from a “rational” business perspective this was insane. After all, what harm would it do for some little kid to have his own stuffed tiger named Hobbes?

Stephan Pastis (Pearls Before Swine) addresses this issue in most detail. After asking that simple question about marketing a stuffed animal, he talks about the difficulty of controlling the limits of merchandising once the door has been opened (Peanuts characters selling insurance); but perhaps more importantly, he says, it was about Watterson’s need to control his creation. Once marketing enters the picture, other people start having a say in decisions involving the strip and the characters, and Watterson simply wanted Calvin and Hobbes to remain his own creation.

Although not addressed in the film, another reason might well be that Watterson could see that any efforts to merchandise his characters would have the inevitable effect of limiting kids’ own imaginations. After all, the entire point of the strip was the limitless creativity of Calvin, so why do anything to restrict actual kids to merely reiterating Calvin’s adventures rather than being inspired to invent their own?

While Schroeder’s film explores these issues and others to do with the changing history of comics, their decline in recent decades as newspapers make available less, and more restrictive, space; as the audience for comics has become more fragmented with the scattering of new work across the Internet rather than being contained within that single print delivery system … the heart of the documentary is the strip itself, teeming with humour, energy, an expansive sense of life, all rendered with exquisitely expressive drawings which evoke Watterson’s hometown of Chagrin Falls, Ohio. Schroeder’s affection for the strip is reflected in all the interviews, whether with professional comic artists, curators, publishers or with people who just happen to be fans and admirers, and the film has the power to reignite one’s own forgotten appreciation for Calvin and Hobbes. The limitations Watterson imposed on his own creation not only prevented the strip from dragging on into tedious old age (Blondie? Beetle Bailey? Dennis the Menace? …), it ensured that the saga of this small boy and his wry stuffed tiger exists as a fully formed, self-contained work of art which almost twenty years after its final appearance in newspapers remains as fresh today as when it flowed from the tip of Bill Watterson’s pen.

Comments