Rossellini & Bergman: a collision of life and art

When approaching 3 Films by Roberto Rossellini Starring Ingrid Bergman, Criterion’s new 5-disk DVD edition of the first three collaborations between the Italian filmmaker and the Hollywood star, it’s difficult not to feel a certain degree of trepidation. These three films, critical and commercial failures at the time of release, now stand as something like cinematic monuments, hugely influential (as Rossellini’s neo-realist films had been before them) in transforming the ways in which movies were made in the post-war years and, more importantly, what films were made about.

In the years immediately after World War Two, Rossellini rose to international prominence with his war trilogy – Rome Open City, Paisan and Germany Year Zero – which helped, along with the work of Vittorio De Sica, Luchino Visconti and others, to create a new way of movie-making. These films mixed actors and non-actors on starkly shot real locations to produce a sense of immediacy and realism which went against the grain of polished studio product.

In those same years, Ingrid Bergman was one of the most famous and highly-paid actors in the very polished studio movies of Hollywood. In the ten years following her arrival in the States, the Swedish actress had starred in a string of hits, being nominated four times for an Oscar, winning once in 1945 for Gaslight, and gathering a huge number of fans who viewed her as the epitome of charm and purity. But towards the end of the ’40s, she appeared in several less successful movies and was beginning to feel too constrained by her screen image. That was when she saw Rome Open City and Paisan; she was so impressed that she immediately wrote to Rossellini to offer her services as an actress in any project he cared to name.

The films which resulted from their collaboration are inextricable from the relationship which developed between them; during the shooting of the first, Stromboli, they fell in love and Bergman, although still married to her Swedish husband, with a young daughter back in the States, became pregnant. The explosion of publicity was remarkable, but perhaps inevitable. The affair and the pregnancy were a complete violation of the image the actress had projected for years on screen and this very public discovery that she was actually a woman with strong emotional and sexual drives offended the puritanical heart of America.

Bergman married Rossellini, and in five years together they had three children and made five films. The Criterion set presents the three made in Italy and released between 1950 and 1954. Each of these deals with a marriage in crisis; each is largely viewed through the eyes of the woman (although in both Stromboli and Journey to Italy there is definite empathy shown towards the husband, something entirely absent from Europe ’51). And all three experiment with the image of Bergman as a star as well as exploring new possibilities for cinematic narrative. At the time, their personal and professional relationship was viewed as something like career suicide for both of them; now the resulting films can be seen as a determined attempt to forge a new kind of cinema.

Stromboli (1950)

Stromboli, named after the volcanic island in the Aeolian chain north of Sicily, still has links to the earlier war films, dealing as it does with characters displaced by the conflict and trying to establish some kind of normal post-war life. Like those earlier films, it uses a largely non-professional cast and was shot under arduous conditions on the remote island location, where there wasn’t even any electricity. At the start, Karin (Bergman), a Lithuanian refugee, lives in an Italian camp for displaced persons; she’s waiting to hear whether she’ll get a visa to go to Argentina, when a young Italian soldier named Antonio (Mario Vitale) begins to court her through the barbed wire. When her visa request is rejected, Karin agrees to marry Antonio, despite being unable to communicate with him, and he takes her back to his home on Stromboli.

Karin has for years survived by taking advantage of opportunities as they arose (including a period as the mistress of a German officer), but now it seems that she’s reached a dead end. Life on the island is harsh and unforgiving, as are the inhabitants. The community is grim and strict, shunning any signs of impropriety. Karin quickly offends them with her more open and emotionally expressive northern temperament; although she does make attempts to adapt, she finds life on the island unbearable and begins looking for a way out. She even makes a half-hearted attempt to seduce the local priest who’s sympathetic to her unhappiness.

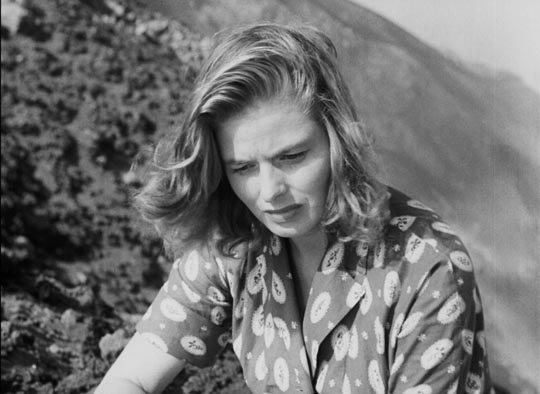

Rossellini makes full use of Bergman’s image as a star to establish the virtual impossibility of her ever being comfortable or happy on the island; but he simultaneously uses that image against her, making her seem at times spoiled and unsympathetic in her fierce resistance to the people around her, a community clinging to the inhospitable soil, risking danger on the sea and from the island itself with its perpetually smoking volcano. There’s a constant tension in the film as viewer sympathy is suspended between the outsider and the simple man who didn’t really understand what he was getting when he married her. A threat of violence simmers just below the surface until the earth itself seems to respond; the volcano erupts, shattering the fragile balance the characters are trying to maintain.

Unable to stay any longer, Karin attempts to escape across the island to the port on the far side, looking for a way back to the mainland, but her arduous climb gradually strips her of the few possessions she takes with her and she reaches the end of her physical endurance before collapsing high on the mountain in despair. The film ends with a tentative sense of epiphany when she wakes in the morning and finds all her fears have left her. It’s by no means clear what she will do now, but she has stopped resisting and in her new openness there’s a suggestion of hope for the future.

One of Rossellini’s main aims as a director was to collapse the distance between actor and role, to remove the artifice of performance by finding ways to get the actors to be themselves as they performed. He worked without scripts, inventing and improvising day by day, even rewriting dialogue in the middle of shooting a scene, a technique guaranteed to provoke vulnerability in an actor used to working in the studio production-line mode. Part of what gives Stromboli its rawness and emotional complexity is the fact that Bergman no longer had all the supports provided by a studio – a finished script, rehearsals, a fixed daily routine on the sound stage; here she was living in primitive conditions, uncertain of what was happening and would happen to Karin. Rossellini even worked Bergman’s own pregnancy into the role, giving added weight to Karin’s flight from her husband, but also to the sudden flowering of calmness and hope with which the film ends …

Europe ’51 (1952)

This hint of a spiritual answer to the harsh problems of life becomes the subject of the next film, Europe ’51, in some ways the most accessible of the three as it makes use of more familiar narrative techniques, specifically those of studio melodrama. Initially, this film seems reminsicent of the work of a director like Raffaello Matarazzo (the object of one of Criterion’s excellent Eclipse sets). Those films make a fetish of a woman’s guilt and suffering in order to intensify the pleasures of redemption. Issues of class are used purely as obstacles to the characters’ happiness, but never seriously questioned on a social or political level.

Europe ’51 draws on these genre elements, putting them under a magnifying glass before embarking on a radical exploration of politics, religion and the state of the post-war world divided between east and west, capitalism and communism, ultimately looking for a spiritual reawakening to escape the crippling existential impasse

Irene (Bergman) and George (Alexander Knox) are a bourgeois couple living in Rome with their sensitive 12-year-old son Michel (Sandro Franchina). Between business concerns and a busy social life, they are barely aware of the boy’s obvious loneliness and despair. During a dinner party one evening, the boy falls to his death in the stairwell outside their apartment and there are suggestions that he actually committed suicide. Irene’s shock and grief cause a rupture in their comfortable life and it doesn’t take long for her husband and mother to become irritated by her inability to come to terms with the loss and resume a “normal” life.

Irene’s realization that Michel in a sense died from her own inability to express love makes her receptive to the influence of family friend Andrea (Ettore Giannini), a communist who awakens her to larger social issues of suffering among the poor and working class. Irene starts to offer what help she can – providing money to help a family with crippling medical bills for their young son; becoming involved with a woman in the slums, Passerotto (Giulietta Masina), who cares for a group of homeless children. But Irene seems unable to establish any boundaries; she even goes to work for a day in a factory to protect Passerotto’s job (a huge, grim place like something out of Lang’s Metropolis, with workers trapped and ground down among vast machines).

Irene’s commitment to the poor, a way for her to act on the love she neglected to give to her son, becomes an embarrassment for her family. She misses dinners and makes them late for the theatre. And finally, encountering a dying prostitute on the street, she disappears for days as she nurses the woman through her final illness, offering a little comfort at the end of her life. When she resurfaces, her family, the police, a psychiatrist all perceive her selfless actions as a sign of madness and she’s committed to a mental hospital where her refusal to renounce her belief in a life devoted to love of others results in permanent imprisonment.

Rossellini started from the idea of exploring what would happen if Christ or the saints were to reappear in the post-war world, and in effect Irene does become a saint as the film progresses, a completely selfless person devoid of ego. And no one likes it. George (representing the Right, capitalism, the West) sees her behaviour as a sentimental embarrassment, a sign of neurotic disease. Andrea (the Left, communism, the East) sees her behaviour as a mistaken diversion from the class struggle. She rejects them both because both Left and Right are rooted in hatred and violence. She believes there’s a third way, a spiritual way. But she even finds herself rejected by the Church. The priest in the hospital essentially tells her that while Christian love is a fine ideal, we all have responsibilities to society’s rules. In short, a genuine compassion and concern for others is perceived as a threat to the stability of a society which is actually maintained by the violent social and political oppositions of the Cold War order.

Journey to Italy (1954)

The third film in the set seems less ambitious than Europe ’51, a small-scale portrait of a troubled marriage (made as Rossellini and Bergman’s own marriage was beginning to disintegrate). Katherine (Bergman) and Alex (George Sanders) are a middle class English couple who drive to Naples to settle the estate of a recently deceased uncle. Stresses are immediately apparent even before they arrive in the city; Alex is a driven businessman who feels anxious and uncomfortable away from work, while Katherine had hoped the holiday might allow them some time to reinvigorate their marriage. But it quickly becomes clear that there is little to revive; their union is a matter of convenience, a business arrangement in which there is little emotional heat, with her role limited to being his social secretary.

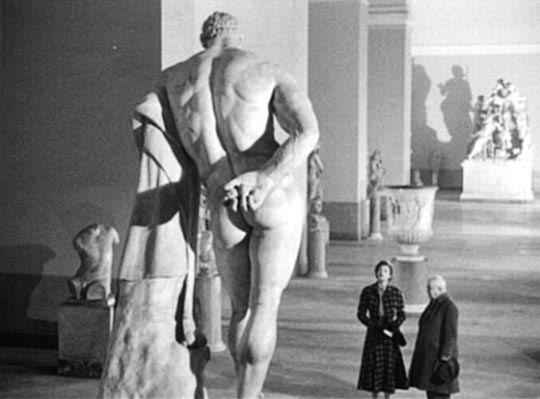

Once installed in the uncle’s villa, waiting for an offer to come in from a potential buyer, the friction sends them off in different directions. While Alex goes to Capri in hopes of having a brief affair with Maria (Maria Mauban), Katherine goes on a series of expeditions which not only explore the city and its surroundings, but actually penetrate layers of human and geological history; at a museum she sees huge statues dating back thousands of years, moments of life frozen in stone; at the temple of the Oracle of Cumae she discovers echoes of a deep and mysterious spiritual past; and on Vesuvius she finds that the earth itself is alive with vital energy. Human life is brief and fragile, but life itself spans eons and still flows though this ancient place.

The crisis in the couple’s marriage comes to a climax during a visit to Pompeii where archeologists are uncovering signs of the people who died during the volcano’s eruption in 79AD. The sight of two bodies, a man and a woman, frozen forever in an embrace at the moment of death, causes Katherine to break down emotionally. But at the moment which seems to confirm the impossible distance between her and Alex, a chance occurrence brings about an abrupt change as startling and seemingly unprepared for as Ethan’s sudden change of heart at the end of Ford’s The Searchers, giving the film what seems like a conventional “happy ending”, but presenting that possibility as a literal miracle.

Journey To Italy is at once the simplest of the films stylistically and the most deceptive conceptually, a narrative which constantly frustrates narrative expectations, in which the film’s meanings lie beyond the characters and their actions (or inactions). While all three of the films in this set explore the idea of a spiritual response to the failures of a materialist view of life, Journey to Italy is perhaps the most oblique.

Rossellini’s improvisational method apparently infuriated George Sanders, an urbane actor who had recently won an Oscar for his role as the suave, world-weary critic Addison DeWitt in that most urbane and polished of studio movies, Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s All About Eve. He went on record as saying that he didn’t have a clue what Journey was about and indeed very little seems to happen on the surface – Alex’s attempts to reassert his masculinity through a casual sexual encounter (first with Maria, later with a depressed prostitute) come to nothing; Katherine seems to serve merely as a device to provide a travelogue of Naples and its surroundings. Everything of substance occurs beneath the surface, intense emotional and psychological forces like the pressures bubbling below the sulphur pits of Vesuvius; and that final, sudden transformation at the end, as unexpected as it is, is like an inevitable eruption of the volcano, a sudden surfacing of everything the characters themselves have been unable to express to one another.

The disks:

Criterion’s 5-disk set presents the three features in variable states of preservation. Stromboli and Europe ’51 show a lot of print wear, with fine scratches throughout and occasional larger instances of damage. Taken from prints rather than original negatives, the transfers exhibit varying contrast levels and occasional image instability. The restoration of Journey to Italy provides a much sharper, cleaner image, with rich blacks and good contrast. Inevitably, the English language tracks are uneven, with the dubbing occasionally a little jarring (everyone in Rome in Europe ’51 sounds like New Yorkers).

The supplements:

Perhaps most significantly, Criterion offers alternate Italian versions of Stromboli and Europe ’51. Given that all the films were created around the presence of Ingrid Bergman, it’s possible to view the English versions as the primary, “official” versions of the films. But the Italian versions are not simply re-dubbed copies of these; they have different lengths and to a degree different content. Film historian Elena Dagrada provides a 40-minute analysis of the differences between the various versions of Europe ’51, which present different emphases on political details.

Each film has a brief introduction by Rossellini from French television broadcasts in the ’60s, and each is accompanied by an interview with film critic Adriano Apra. Journey to Italy has a full-length commentary by Laura Mulvey, in which she makes a forceful case for the film’s being the “birth of modern cinema” with its oblique, allusive technique which proved highly influential on the French New Wave.

Spread across the five disks are a number of documentaries: Rossellini Under the Volcano (1998) about the making of Stromboli; Rossellini Through His Own Eyes (1992), which surveys the director’s entire career and approach to filmmaking; Ingrid Bergman Remembered (1995), a personal reminiscence of the actress by her daughter Pia Lindstrom.

There are visual essays by critic James Quandt (Surprised by Death) and Tag Gallagher (Living and Departed); two short films – The Chicken (1952), a vignette by Rossellini starring Bergman, and My Dad Is 100 Years Old (2005), an impressionistic portrait of the director by his daughter Isabella Rossellini, directed by Guy Maddin; plus new interviews with Martin Scorsese, Ingrid and Isabella Rossellini (the couple’s twin daughters), and G. Fiorella Mariani (Rossellini’s niece), accompanied by Bergman’s home movies.

This dense, demanding set is the kind of thing Criterion was made for and will likely be seen as their finest and most important release of the year.

Comments