Thinking About Genre, part 1

For such a type to be successful means that its conventions have imposed themselves upon the general consciousness and become the accepted vehicles of a particular set of attitudes and a particular aesthetic effect. One goes to any individual example of the type with very definite expectations, and originality is to be welcomed only in the degree that it intensifies the expected experience without fundamentally altering it.

– Robert Warshow

“The Gangster as Tragic Hero” Partisan Review, February 1948

The fundamental concept of genre has existed to some degree since human beings first began to create. Even cave paintings exhibit various conceptual patterns which, although their original purpose may have had magical elements, exhibit an underlying drive to impose order on the world they represent. This same desire for order was manifested in the rules of ancient Greek drama and comedy, in the illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages, Jacobean tragedy and Elizabethan drama …

The particular rules shift and evolve (Shakespeare’s plays definitely don’t adhere to the Greek prescriptions regarding unity of time and place), but always human creativity requires rules and forms of some kind in order for its products to be intelligible. When artists push hard against these boundaries, their work is often met with confusion and even outrage – works we now regard as classics were booed; Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, with choreography by Nijinsky, virtually triggered a riot when it debuted in May 1913. Such works did not conform with their audience’s expectations.

I’ve always remembered a line from Quality Time, a film by Darrell Varga, who shared the job of equipment coordinator for the Winnipeg Film Group when I first got involved with the WFG in the late ’80s: “I know what I like because I only like what I already know.” Particularly in popular culture audiences resist being genuinely surprised, preferring the comforts of the familiar – hence Hollywood’s decades-old obsession with sequels and remakes, many of which continue to make very good profits.

Although I enjoy the familiar pleasures of particular genres, there’s no denying that forms can atrophy to the point of tedium – just try to watch a few western B-movies from the ’30s and ’40s, where the narrative tropes were so formulaic that it’s difficult to tell one from another. But when a filmmaker prods those tropes onto a slightly different tangent, the western can be as stimulating as any good drama – Anthony Mann’s psychological westerns; Nicholas Ray’s sexually-charged, gender twisting Johnny Guitar; Sergio Leone’s reconfiguration of the historical myths which by sheer repetition in American arts and popular culture had by the ’60s taken on the air of actual history. Could Peckinpah have gone so quickly from the classical western (Ride the High Country, 1962), through the chaotic experiment of Major Dundee (1965), to the radical smashing of the genre in The Wild Bunch (1969) if Leone, Sergio Corbucci and others hadn’t already deconstructed the atrophied form?

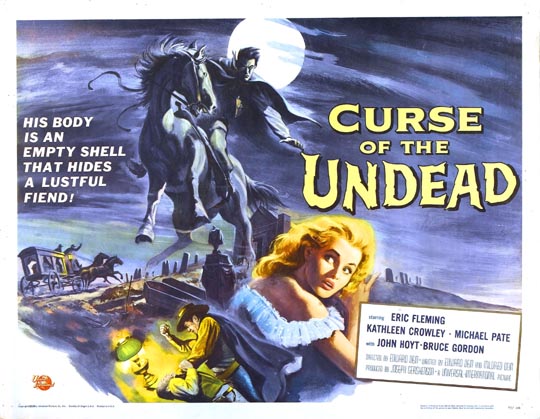

Although I can enjoy a genre movie for its familiar elements (I like Charlie Chan, Mr Moto, Dracula and Frankenstein, among others), I also like films which severely bend their parent forms and even combine two or more genres. I can recall seeing Edward Dein’s Curse of the Undead (1959) on TV sometime in the late ’60s and enjoying the surprise of finding a vampire story in western dress. And I was put into a state of euphoric delight when I discovered W.D. Richter’s The Adventures of Buckeroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension in its brief, generally negatively received theatrical run in 1984. While movies like Buckeroo Banzai and Don Coscarelli’s Bubba Ho-Tep and John Dies At the End often seem to produce confusion in audiences and critics who strive to figure out just where they fit genre-wise, I enjoy the sense of being cut adrift from prior expectations.

Although the critics in general have seemed weary of superhero movies for a few years now (with the occasional exception of numbingly pretentious rubbish like Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy), audiences still can’t seem to get enough, making successes of the nth reiteration of Superman or Spider-Man. It’s hard not to believe that it’s the familiarity of the material itself which draws an audience, because films made with as much if not more enthusiasm and care, and certainly with comparable technical skill, but with less familiar narrative content, often seem to tank at the box office and find themselves quickly buried under ridicule and contempt.

Last year, Andrew Stanton’s rousing adaptation of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Princess of Mars, admittedly hampered by the dull, un-evocative title John Carter, got no respect at all. Yet it captures the essence of its source beautifully. Problem is, that kind of pulp fantasy is no longer familiar to the mainstream and now looks as if it’s derivative of Star Wars and Indiana Jones, where in fact those movies were slick pastiches of the kind of thing Burroughs had been writing sixty years earlier.

The same fate befell Guillermo Del Toro’s Pacific Rim this summer. This epic is rooted in two genres which may be peripherally familiar to a mainstream audience, but are generally viewed with an attitude of superiority, and even contempt. In this age of CGI, the Japanese kaiju (giant monster) movies are perceived as being naive, crude and mostly for kids. To a fan (and Del Toro is a huge fan), these films are cherished, not because they are crude or primitive, but because the level of craft invested in the creation of their fantasy worlds is awe-inspiring. The other genre, mecha, is most often associated with a whole lot of Japanese TV shows involving kids and giant robots, but is also one of the mainstays of anime.

Del Toro and co-writer Travis Beacham set out to take these two genres and create a fresh narrative to explain and justify the existence of both. Then the director and his technical team rendered the movie’s world with a phenomenal attention to detail. But perhaps most importantly, Pacific Rim was made with great affection by someone who was willing to risk looking foolish or naive by not turning it into a parody or, worse, a joke. One of the key factors in great genre fiction and movies is that the creator takes the material seriously – that is, at least for the duration of the story. This is what gives a movie like Ishiro Honda’s Mothra, his most poetic kaiju fantasy, its enduring charm; the giant moth is a ridiculous concept rendered with conviction.

I liked Pacific Rim when I saw it in IMAX 3D, and I found myself liking it even more watching it again in 2D on Blu-ray. And then, surprisingly, I liked it even more when I listened to Del Toro’s passionate and detailed commentary track and watched all the production featurettes included on the disk. Here’s a huge, effects-heavy film made without a trace of cynicism by someone who seems amazed that he was given the means to recreate the pleasure he felt as a child in encountering all those Japanese fantasies (just as Andrew Stanton strove to recreate what he had experienced reading Burroughs as a child). It’s that child-like delight in robots and giant monsters, in heroes and heroic sacrifice (and of course, in seeing some large-scale destruction) which makes Pacific Rim what it is.

And as William Gibson has pointed out, you need to love the movie for what it is, not complain that it isn’t something else that you were expecting. It’s a big kids’ fable made with every resource available to a contemporary filmmaker. Yet there seems to be a much bigger audience for the utterly cynical, emotionally empty Transformers movies that Michael Bay is apparently destined to churn out ad infinitum. Go figure.

To be continued …

Comments