Thinking About Genre, part 2

A lot of my movie viewing is genre based. My appreciation of familiar forms and variations goes back to childhood, when fantasy, horror and science fiction first appealed to me. Mysteries and thrillers came a bit later, for some reason – maybe because they’re at least to some degree rooted more in reality than imagination. I think I was even older when I took any real interest in westerns. A lot of this was, I might say, instinctual; I didn’t make conscious choices, just responded to what I encountered with more or less interest and began seeking out things which triggered the strongest reactions. Who knows why and how particular tastes develop?

And of course our responses are largely a matter of taste. But it seems to me that those responses are also governed by the internal rules of any particular movie, rules which are tied to its generic origins. If there’s a ghost in the story, our first obstacle is to accept the existence of a ghost. Some people won’t go that far and immediately dismiss the story as nonsense. But once we’ve decided to go along with the idea of the ghost, we need to understand the rules of its behaviour … and the story will satisfy or disappoint according to how coherent or arbitrary those rules are. And, of course, depending on one’s individual tolerance, the reactions of the characters to the ghost will play a part … but that aspect is more in line with the simple rules of drama than necessarily with the genre elements of the story.

In terms of personal preference, I’d much rather watch the Paranormal Activity movies than things like Saw or Hostel. What many seem to find boring, I see as subtlety. It’s the incremental accumulation of small details – and the growing sense of uneasiness which makes you carefully explore the films’ static frames for signs of disruption – that generate a sense of fear. That is, in the best Val Lewton tradition, the PA movies get the audience to do the work of conjuring up what each viewer finds most scary. The gross, visceral shocks of Saw and Hostel only have an impact in the moment, while (for me) the creepiness of PA lasts much longer, making me aware of small sounds and shadows in the room around me in a way which recalls childhood fears of the dark – the effect is deeper and more primal.

It’s this interior, under-the-skin effect which makes a good ghost story scarier than a psycho killer/slasher movie. The fears evoked are less tangible, and thus more difficult to reason away. But even within the ghost story there’s room for variation. In the Paranormal Activity movies, there’s a certain literalness to the use of the supernatural; the ghosts and demons serve to make the material security of middle class suburban homes less assured (and they prey on the very real unease surrounding the fact that for some eight hours every day, we lie unconscious and completely vulnerable in our beds). They’re an assault on complacency. But their power has diminished over the duration of the series as the filmmakers have felt the need (not surprisingly) to elaborate on the underlying narrative, with uncertainty being replaced by a malevolent coven of witches which has dragged the most recent film into the realm of B-horror, originality replaced by cliche. Too much explanation undermines the sense of unease (something Japanese filmmakers understand well, which is why so many movies in the first wave of J-horror remain so creepy and disturbing).

More traditional ghost stories exploit the metaphorical possibilities of the supernatural. One of the most common themes found here is guilt, the shadow of some past crime which impinges on the present, seeking redress. This can be found in recent work like Joe Ahearne’s BBC adaptation of James Herbert’s The Secret of Crickley Hall and movies like Peter Medak’s The Changeling and Guillermo Del Toro’s The Devil’s Backbone (which ups the stakes by adding an additional layer of political/historical crime – the Spanish civil war – to the story of personal guilt).

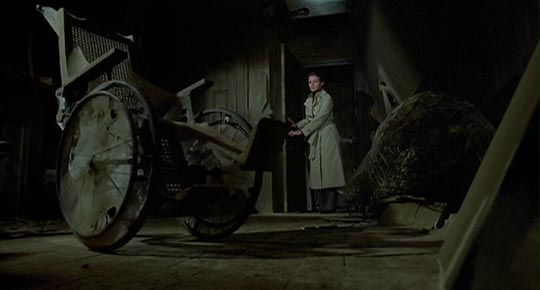

These narratives are about the impact of bad deeds. Other ghost stories focus more on the shadows of individual psychology: in both Jack Clayton’s The Innocents (adapted from Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw) and Robert Wise’s The Haunting (adapted from Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House), the supernatural is highly ambiguous, possibly nothing more than the projection into reality of the two stories’ protagonists’ neurotic fear of and attraction to sex. Both Miss Giddens (The Innocents) and Eleanor (The Haunting) are so frustrated that they become hyper sensitive to the erotic potential of the world around them, perhaps conjuring up ghosts (like the monster from the id in Forbidden Planet) to wreak havoc on the people around them. A similar situation can be found in John Hough’s The Legend of Hell House (adapted from Richard Matheson’s Hell House), although in this case the destructive neurosis resides in the dead Emeric Belasco, a man driven to violence and perversion by a deep sense of physical inadequacy.

All of the films just mentioned scrupulously stick to the narrative rules they set up. This is one of the reasons an audience can find themselves feeling so satisfied even as they experience fear. After all, it doesn’t really seem logical that we’d find fear entertaining; it’s the balance between unease and the paradoxical sense of an ordered world provided by the rules which produce our sense of pleasure … even if those rules might result in a downer ending (tragedies are satisfying because of the rules which determine their narrative structure).

Which is why I’m sometimes puzzled by the popularity and success of movies which lack this kind of coherence, and the failure of others which seem so well constructed to me. A minor work like Nimrod Antal’s Armored, which is a finely wrought heist movie, a modern noir in which the protagonist is caught up in events which threaten his sense of order and morality, which he must navigate not only to save himself physically but also to maintain his moral integrity – such a film often finds itself dismissed by critics and avoided by audiences who seem to think there’s nothing much going on in it. But bloated messes like Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight and The Dark Knight Rises end up with raves from critics and the kind of fan adulation that leads to on-line death threats against anyone who dares to find them lacking.

My chief problem with the Dark Knight movies goes beyond the sheer ponderous joylessness of the filmmaking, an exhausting heaviness which seeks to crush the viewer into submission, to the startling lack of narrative coherence and embarrassingly bad story construction. Superhero movies by their nature are parables about good and evil, sin and responsibility – weighty themes, for sure, but rather simplistic when dressed up in tights and masks – more akin to Medieval morality plays than drama; Nolan’s approach, which strains for some kind of Shakespearean gravitas sucks all the pleasure out of the clash between good guys and bad guys.

Nolan’s trilogy reflects a fairly recent trend in “flawed heroes”, the need to undermine the confidence of good guys which may reflect the very genuine doubts we have about the motives of those who loudly proclaim that they are doing good in the world. But a superhero movie is not about the real world; it’s about archetypes and symbolic examples. They’re stories, not documentaries, and Bruce Wayne’s interminable moping – particularly in the third film, which seems to waste almost an hour with him sitting at the bottom of a hole wallowing in self-pity – ends up being utterly uninspiring.

Worse, Nolan attempts to graft real-world contemporary politics onto his cumbersome action narrative, referring to the current economic situation, the outrageous gulf between rich and poor, and the Occupy movement … but he hasn’t thought it through and as the story plays out, it becomes apparent that it can’t support that reality: no matter how many contortions the script goes through, we end up with the poor (Occupy) being presented as stupid dupes of evil forces, and the wealthy (Bruce Wayne and friends) are left to save the day. The veneer of serious drama grafted onto the comic book narrative proves to be utterly bogus and the film fails either as escapist action-fantasy or as comment on the real world.

Where movies like Buckeroo Banzai and John Dies at the End gleefully mix and match genre elements, eager to see what kind of sparks they can generate with the collisions they cause, Nolan buries his genre under layers of directorial concrete, causing atrophy and lifelessness. Is this because, unlike W.D. Richter and Don Coscarelli, he doesn’t take much pleasure in his chosen genre, perhaps afraid that he won’t be taken seriously if he doesn’t smother it with faux seriousness? Or is it something larger, less personal? Is the mainstream, obsessed with these heavy big budget epics, starting to forget the simple basics of storytelling? – and are audiences, accustomed now to unmotivated movement and noise, starting to forget the simple pleasures of being told a story?

Comments

Good stuff, as usual.