Genre On Disk, part two

As the big distributors increasingly cut back on disk releases of smaller titles, the boutique companies continue to fill some of the gaps – some like Olive Films offering bare-bones disks of often obscure movies, others like Shout! Factory continuing to offer disks loaded with supplements. I seem to have been buying quite a few Blu-rays recently from both these labels.

Shout! Factory

John Carpenter is a director who has devoted his entire career to genre movies (even his Elvis adheres to the rules of the bio-pic). After his auspicious start with the great student film Dark Star (1974, as much the work of eccentric co-writer Dan O’Bannon as of Carpenter himself), Carpenter, a big fan of Ford and Hawks, wanted to make a western. But by the mid-’70s that genre had little commercial weight and budgeting a period action movie was beyond his means. However, genres are nothing if not flexible, so Carpenter went ahead and made his western by transposing the core story of Hawks’ Rio Bravo (1959) to a bleak contemporary urban wasteland, an abandoned area of East Los Angeles where a handful of people trapped in a decommissioned police station undergo a vicious siege by a deadly gang. Assault on Precinct 13 (1976) features a young lieutenant on his first night of duty, a couple of young women support workers, and a couple of prisoners, including Napoleon Wilson, on his way to execution for an unspecified crime. Under attack, this group has to overcome internal conflicts in order to fight together to survive the night, gaining mutual trust and respect before the apocalyptic climax. Even here, at the start of his career, Carpenter showed a great sense of widescreen composition and a willingness to push things beyond the normally accepted limits of commercial movie-making, an advantage of working inexpensively on the fringes of the business (the early shock moment by the ice cream truck signals that the audience can’t comfortably anticipate what’s going to happen based on prior experience).

Despite the huge success two years later of Carpenter’s follow-up feature, Halloween, he has never made the transition to the big-time mainstream – there was that Elvis biopic (1979) made for television; the sentimental Starman (1984), which almost seemed like an atonement for having offended a lot of people with his masterpiece, The Thing, the same summer that Spielberg brought out ET; and the expensive misfire Memoirs of the Invisible Man (1992) – but for the most part he has stayed on the fringes, making horror and fantasy movies, sometimes with great visual flair, sometimes seemingly by rote. Sometimes obvious budgetary limitations hamper an ambitious idea (They Live [1988] being perhaps the prime example); occasionally he has had enough money to realize those ambitions, as in his two best films, The Thing (1982) and Big Trouble In Little China (1986). And at other times, the ambitions themselves seem constrained, resulting in something which hints at interesting ideas but fails to develop them beyond a perfunctory suggestion.

Prince of Darkness (1987) falls into the latter category. Carpenter was obviously a fan of British television writer Nigel Kneale and even hired Kneale to write a franchise-changing script for Halloween III. That didn’t work out so well, with Kneale’s script being jettisoned in favour of director Tommy Lee Wallace’s rewrite (though some typical Kneale ideas still poke through the mediocre surface of the movie). Perhaps Carpenter thought he was making amends for that sorry situation when five years later he wrote the script for Prince of Darkness under the pseudonym Martin Quatermass, a nod to Kneale’s most famous creation, and incorporated some ideas borrowed from Kneale, particularly Quatermass and the Pit (TV, 1959; feature, 1967). The set-up for the film is promising; beneath a seemingly abandoned church, an ancient sect of monks has been keeping watch over a cylinder in which the essence of evil – Satan, in fact – is imprisoned as a seething, primal liquid. People are starting to experience visions in their dreams which are apparently messages from the future warning of the triumph of Satan; a handful of investigators brought in from the university to study the cylinder find themselves in a struggle to prevent the Evil One’s escape. Meanwhile, outside the church a horde of homeless people (led by Alice Cooper) are turning into mindless zombies determined to prevent the team from preventing Satan gaining his freedom. Unfortunately, after setting this up, Carpenter does nothing with the idea except stage a stream of cliched zombie attacks which have the tired familiarity of numerous B-grade movies of the time.

Both Assault on Precinct 13 and Prince of Darkness are given decent transfers by Shout! Factory which reflect the films’ low budget origins, and each disk includes interesting supplements, including commentaries and interviews with various participants in the productions.

As modest as Carpenter’s movies are, they’re monumental compared with Sam Firstenberg’s Ninja III: The Domination (1984), an absurd yet entertaining attempt to drag Asian martial arts into an American milieu. Implausible power company lineman (linewoman?) Christie (Lucinda Dickey) finds her life going to hell after an encounter with a dying ninja in the desert. The evil assassin takes possession of her, giving her awesome fighting powers in spells during which she blacks out, not aware of what she’s doing as the deadly spirit seeks revenge against his enemies. Meanwhile Yamada (Sho Kosugi) arrives from the East on the trail of the assassin. As he fights the evil while simultaneously trying to protect Christie, the film goes through a series of cheesy fights with occasional hints of the philosophy which runs through genuine Asian martial arts movies.

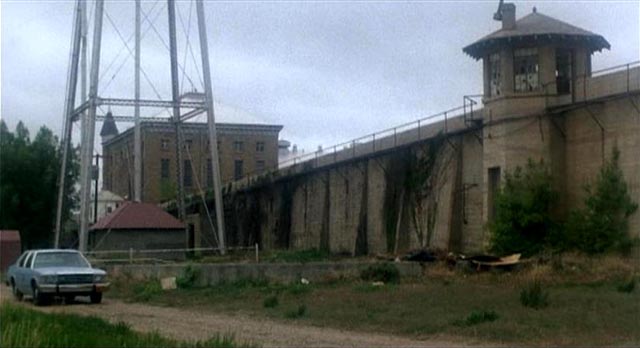

Somewhat more successful on a basic filmmaking level, Renny Harlin’s first American movie (after a single Finnish feature, Born American [1986], made with the obvious aim of attracting interest in the U.S.) is a mix of prison drama and ghost story called, simply, Prison (1988). Starring a young Viggo Mortensen as one of a group of prisoners brought to a previously abandoned penitentiary, reopened because of state budgetary issues, it benefits from its grim, derelict setting (an actual decommissioned prison), which Harlin exploits with an often mobile camera. The story involves the vengeful spirit of a wrongfully executed man reawakened by the arrival of the new prisoners and the return of the corrupt warden responsible for his death. Although Harlin stages the action efficiently, the film could have benefited from a brisker pace. Nonetheless, it illustrates the value of finding ways to combine different genres to create fresh narrative possibilities and revitalize familiar effects.

Also from Shout! Factory, the first really decent home video version of L.Q. Jones’ adaptation of Harlan Ellison’s famous novella A Boy and His Dog (1975) highlights all the strengths and faults of this highly influential movie (godfather to Mad Max and the whole genre of post-apocalyptic survival stories). One of the most faithful transfers from print to screen, it has a stark assurance which shows that Jones had learned a great deal from the directors he’d worked for in a long acting career (including Sam Peckinpah, Don Siegel, Bud Boetticher). The film has an uncluttered feel, scenes pared down to essentials, no time wasted … all of which works very well to evoke a convincing world in which all human action is reduced to the minimum required for survival. Jones trusts his audience to understand what’s going on without belabouring explanations … when we first encounter Vic (a young Don Johnson) scouring the desert wasteland for supplies, we are expected to grasp and accept the fact that he’s in telepathic communication with his dog Blood (voice of Tim McIntire) and, more importantly, that Blood is the brains of the pair. Vic is a horny adolescent given to acting without thinking, no matter how hard Blood tries to educate him.

And it’s that element of Vic’s character which gives rise to the problematic aspects of the film (which also exist in Ellison’s original story); the film takes Vic’s view of this shattered world as its own, giving rise to accusations of misogyny. I’m not sure there’s a clear answer to this problem; does the depiction of unacceptable attitudes imply an endorsement of them? The fact is that one of the tropes of this particular genre tends to be an objectification of women; in popular imagination these survival narratives tend to be “masculine”, with women becoming objects of trade and consumption. This theme, although countered somewhat by the film’s mid-section, remains largely unchallenged at the end with the controversial choice Vic ultimately makes between his loyalty to Blood and whatever connection he has made with Quilla June (Susanne Benton).

That mid-section, beginning with Vic’s being lured underground by the nubile Quilla June, shifts the film’s tone into outright satire with its depiction of a grotesque middle class America surviving after the nuclear holocaust in a re-creation of small-town values pushed to fascist extremes, with conformity enforced by robots designed to look like hick farm workers. Down there in a perpetual subterranean night, this parody of Nixonian America is slowly dying, being killed off by the sterility of the men; girls like Quilla June are used to snare virile surface dwellers who are then “milked” to impregnate all the fertile women and so perpetuate this futile society. The reversal implicit in this, the reduction of the horny Vic to his most useful anatomical feature, to some degree critiques the attitudes visible up on the surface, but in the end the film comes down firmly on the side of that surface world, as stark and unpleasant as it might be, and so finally seems to endorse Vic’s adolescent reduction of women to objects for his own momentary pleasure.

Some of these issues are touched on in the lengthy conversation between Jones and Ellison included on the disk, but it’s never fully explored. The pair are very candid about their conflicts over the adaptation, however, particularly the final spoken line which transforms the deeper implications of Ellison’s original ending into a crude joke which reinforces the more critical interpretation of the story which has led to quite a few negative reviews over the years.

Olive Films

Three very different movies from the eclectic Olive Films label illustrate the range of options even within familiar genres.

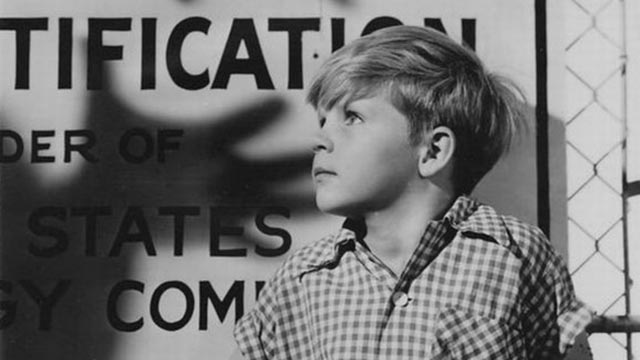

The Atomic City (1952) was the first feature of Jerry Hopper, who quickly followed it with another thirteen features in five years before devoting the next fifteen years almost exclusively to television work. The Atomic City is a family drama and a crime film set against a Cold War background. The script by the prolific Sydney Boehm was nominated for an Oscar, which seems a little odd now because the film has the flavour of a B-movie with a slightly broken structure. It begins with the semi-documentary style common to thrillers of the period, sketching in the life and work of the community of Los Alamos, centre of the U.S. nuclear industry. The Addisons, scientist Frank (Gene Barry), housewife Martha (Lydia Clarke), and young son Tommy (Lee Aaker), seem like a typical middle class suburban family, but Martha is disturbed when Tommy casually says at lunch one day “If I grow up …” She senses that their environment is unhealthy for the boy, but both parents accept the need for the constraints of the national security state which has grown up around nuclear energy.

When Tommy is kidnapped by enemy agents in an effort to pressure Frank to hand over the secrets of the hydrogen bomb, the couple are suddenly presented with an impossible choice: the life of their son or the security of the country. There is a similarity here to Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much, although in both versions of that story the political element is merely the MacGuffin setting the plot in motion. In fact the dilemma for the parents there is not one of choosing between betraying their country and saving the life of their child; they’re called upon to act heroically to prevent an assassination – the peril triggers a rousing display of heroism rather than a murky moral ambiguity.

In The Atomic City, for the authorities who eventually become involved there’s no question of a choice – security comes first and the kid must be sacrificed if necessary for the greater good. But in the second half of the film, Boehm’s script backs away from the implications of the set-up, becoming an extended chase and last-minute rescue with family and authorities defeating the bad guys in a final desert showdown which ultimately leaves intact the idea of the “necessity” for a police state to protect “freedom”. Although it ends happily for the family, the idea that any and every citizen, even the most vulnerable, is ultimately expendable when it comes to protecting the state remains unquestioned. The issues raised and then skirted by The Atomic City have only become more pressing in the decades since it was made, with western governments increasingly exercising their authoritarian muscles against their own populations in the name of “security”.

Hubert Cornfield’s career spans roughly the same period as Jerry Hopper’s, but he only directed a handful of features and, in the ’70s, some television in France. He’s probably best known for his unsettling kidnap movie The Night of the Following Day (1968), starring Marlon Brando and Pamela Franklin. But a decade before that, he made a small, stark heist movie called Plunder Road featuring a cast of character actors and a script with very little dialogue. The tone of Plunder Road (1957) is late noir infused with the fatalism of French existentialism, like a sketch inspired by Clouzot’s The Wages of Fear (1953). After an elaborate, almost wordless opening sequence in which the gang rob a train carrying a shipment of gold, the five men split the take into three parts, hiding each in a different truck, and then setting off on a long drive to the coast where they are scheduled to meet up again for an equally elaborate plan to get the gold out of the country.

In the traditional heist movie, the elaborate planning and mechanics of the job are almost always followed by a breakdown within the group; personality clashes and individual psychological issues undo all the careful plans, leading to the destruction of the gang and the loss of the stolen loot. In contrast to this, Plunder Road isolates the gang members from one another and, although character flaws play a part, it seems more the arbitrary workings of fate which defeat these five men – momentary lapses of judgement, or inattention, expose them one by one to the forces of the law. There’s a tone of hopelessness which echoes Clouzot’s film (and William Friedkin’s still-underrated remake, Sorcerer [1977]), which comes very late in the noir cycle and to some degree prefigures the harsh eruptions of violence and doom in the late ’60s and early ’70s (Bonnie and Clyde, The Wild Bunch, Mean Streets).

Before Robert Altman hit it big with M*A*S*H in 1970, he had served a long apprenticeship in television. In fact his first feature was made for TV in 1964, a tense little thriller called Nightmare In Chicago which inexplicably remains unavailable on home video. His second theatrical feature (after the bleak sci-fi movie Countdown in 1967 – available from Warner Archive), made in Vancouver on a low budget the year before M*A*S*H, is a tense little psycho-drama, essentially a two character piece about loneliness and madness which in some ways is a precursor to Images (1972); in fact, while less ambitious than that later film, That Cold Day In the Park is probably more successfully realized within its own limited terms.

Frances Austen (Sandy Dennis) lives alone in a highrise apartment overlooking a city park. One rainy day, she sees a young man hunched on a park bench in the rain; the man stays there for a very long time, and eventually Frances goes out and offers him temporary shelter. There’s something a bit off about The Boy (Michael Burns), he appears to be homeless, with some undefined mental problems (he refuses to communicate verbally). Frances, who herself has some vague neurotic problems, takes on a mothering role, feeding and clothing The Boy, buying him gifts, allowing him to come and go. It’s fairly late in the film before we step outside the world of the apartment and learn more about The Boy, that he has a troubled home life and that his mentally troubled, homeless persona is an act he puts on, a game he plays.

There are some parallels here to Roy Boulting’s Twisted Nerve (1968) and the movie fits nicely into that decade’s long run of post-Psycho demented horror, but in Altman’s film the roles are reversed as it eventually becomes clear that Frances is the really troubled one and that The Boy has chosen to play his game with the wrong woman. The psycho-sexual complications pile up (Frances, in a truly perverse gesture of “motherly” concern, hires a prostitute and brings her home as a gift, leading to the catastrophic, bloody climax) with a raw sense of discomfort which is more powerful than the artier effects Altman later aimed for in Images. Here we see a skillful director honing the talents he developed through years of work in the conventions of television just before he began exploring a freer, alternative approach to production which eventually resulted in one of the most varied and interesting bodies of work in all of American film; following this, beginning with the over-rated M*A*S*H, he spent much of the next four decades deconstructing genres rather than working within them.

*

I’ll stop here as I have less to say about the war conventions of The Eagle Has Landed (1976) and Force 10 From Navarone (1978); the cheap sci-fi elements of Edgar G. Ulmer’s minor, if sometimes interesting, The Amazing Transparent Man and Beyond the Time Barrier (both 1960); the small pleasures of Jean Yarborough’s The Devil Bat (1940) and Anthony C. Ferrante’s Sharknado (2013), which typically had no chance of living up to its title and concept; and the dismal genre failures of Marc Forster’s World War Z (2013).

Comments