Ghosts of Television Past, part one

The English love ghost stories. There are the classics, of course – Hamlet and Macbeth, for instance – but after the advent of Gothic literature in the late 1700s, spirits, whether harmful or helpful, became less distant, increasingly incorporated into contemporary life. From penny dreadfuls to Dickens, ghosts impinged on the lives of characters not far removed from those of their readers. But in general, as a generic element in Victorian fiction, these ghosts served fairly quotidian purposes. They appeared to offer warnings, to point to concealed treasures, to expose murderers by revealing dead bodies … even, in the hands of someone like Dickens, to provide an allegorical message about social responsibility.

There are numerous writers who specialized to some degree in the ghost story, or at least dabbled in the genre: the novelist and Egyptologist Amelia Edwards; Vernon Lee (the pen name of Violet Paget); Mary Elizabeth Braddon; E.F. Benson; and perhaps most famously M.R. James. James, in fact, virtually came to define the English ghost story with three dozen stories published in the first three-and-a-half decades of the 20th Century. In James’ stories, the supernatural intrudes into an English milieu defined by cosiness and gentility, his protagonists reflecting his own personality, that of a retiring academic and antiquarian whose life is disrupted by something which violates a deeply ingrained sense of certainty about the world. (In this, James was an obvious precursor to H.P. Lovecraft, who seems to offer an almost pathological extension of this central motif into nihilistic despair.)

James’ stories were often written to be read aloud at small gatherings on Christmas Eve and in that spirit, the BBC began to adapt them in the late ’60s as A Ghost Story For Christmas. (Actually, the BBC had first adapted James in 1954, three years before Jacques Tourneur directed Night of the Demon, an adaptation of James’ Casting the Runes; and in the mid-’60s ABC Television included several James’ adaptations in their Mystery and Imagination anthology series – one of my earliest, most indelible memories of television is a moment from that series’ Lost Hearts involving barrels in a wine cellar and the vengeful spirits of murdered children.)

The run of BBC Christmas ghost stories was inspired by Jonathan Miller’s brilliant adaptation of Whistle and I’ll Come To You (1968) for the arts program Omnibus, with Michael Hordern giving a career-best performance as Professor Parkins, a cheerfully self-absorbed academic with a strictly rational view of the world. During a holiday on the Norfolk coast, he spends his days walking briskly along the shore and eating picnic lunches. On one of these jaunts, he finds an odd little flute sticking out of a grave clinging to the eroded edge of a cliff; back in his room, he cleans it and finds a Latin inscription etched into it: “Who is it who is coming?” After blowing the flute, he begins to sense an odd presence, scratching in his room at night, wafting across the beach towards him. The ghost here, if that’s what it is, remains undefined, both in nature and purpose, but when Parkins wakes one night to find this presence in his room, stirring up the covers of the second bed, his inability to grasp something so far outside of his rational view unhinges him completely. Miller’s film is both funny and genuinely creepy, seeming to comment on the absurdity of the very idea of ghosts (the manifestation is literally an animated bedsheet) while acknowledging the unsettling limits of rational certainty.

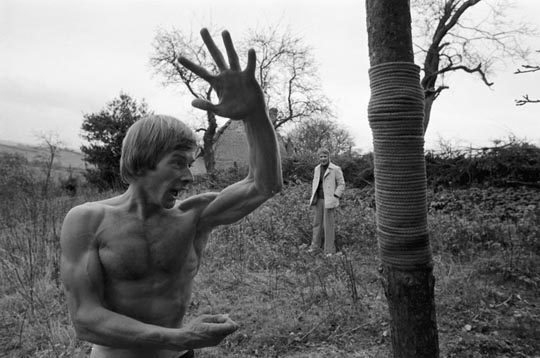

None of the subsequent Christmas stories from the ’60s and ’70s is as rich or disturbing as Miller’s film; seven of the eight were directed by Lawrence Gordon Clark, a competent but uninspired TV director. While there are individual moments which attain a kind of atmospheric dread, none have the cinematic richness of Miller’s work. The weakest is his version of Lost Hearts (1973), in which the promising situation between a creepy “philanthropist” and the orphan he takes in with ulterior motives is undermined by the far-too-prominent presence of the ghosts of two previously murdered children; the excessive makeup and exaggerated expressions of the ghosts come across as silly rather than scary. The most effective overall is A Warning To the Curious (1972), which makes excellent use of its Norfolk locations and benefits from a more generous budget and shooting schedule, making it more film-like than the rest. Strangely, the one which is the most stylistically interesting, The Ash Tree (1975), is referred to by Clark as his “least successful” adaptation (the script was by David Rudkin, who among other things also wrote Penda’s Fen [1974], the legendary Play For Today directed by Alan Clarke); in this story, a young lord moves into the ancestral mansion and finds himself disconcertingly blending with his ancestor who was responsible for the execution of a witch. The editing is at times almost radical as the two time streams are intertwined, and the climax with the lord being attacked by the witch’s “offspring”, a horde of giant spiders with mewling human baby heads, is genuinely nightmarish.

The series of James stories read by Robert Powell and partially dramatized in 1986 and subsequent readings by Christopher Lee in 2000 are less ambitious than the earlier Christmas specials, closer to bedtime stories told around a cozy hearth. All of the James adaptations, plus Dickens’ The Signalman and two original stories (by Clive Exton and John Bowen), are collected in the BFI’s impressive, extras-packed six-disk Ghost Stories For Christmas set.

The set also includes Andy de Emmony’s misguided 2010 version of Whistle and I’ll Come To You. This adaptation manages to conjure a certain amount of atmosphere, but stubbornly limits itself to a dour tone while making its ghost far too literal. John Hurt is Parkins this time, a man crushed by a sense of grief and guilt, having just placed his wife in a nursing home before returning to the hotel where they spent their honeymoon many years ago. A rationalist, he is torn by the idea that although her body is still alive, who she was has simply vanished; he doesn’t believe in survival of the spirit so dementia has left her nothing more than an empty shell. His bleak walks along the shore are a far cry from Horden’s jaunty outings, and his nights are plagued by loud scratchings in the walls and floor of his room, and someone hammering violently on the locked door. He doesn’t find a flute, but rather a gold ring with the same Latin inscription on the inside surface. There are creepy moments, but by the time the ghost reveals itself to be the spirit of his wife insisting on her own continued existence, it all seems rather overwrought and pedestrian in contrast to Miller’s elegant suggestiveness; instead of opening up a mysterious abyss beneath Parkins’ complacent rational certainty, de Emmony’s version shrinks the ghostly manifestation down to a single individual’s troubled psychological state.

The other two recent episodes, from 2005 and 2006, take a more traditional approach. A View From A Hill (dir. Luke Watson) and Number 13 (dir. Pier Wilkie) both present scholars digging into the past and awakening malevolent spirits; both have period settings and excellent, atmospheric locations; and while they may not try to stretch their stories in new and “creative” ways, they’re both much more satisfying than de Emmony’s attempt to graft something more modern onto James.

*

The range displayed in the three surviving episodes of Dead of Night (1972) indicates a series with no overriding theme. Don Taylor’s The Exorcism is a kind of political nightmare in which two complacent middle class couples are confronted by the malevolent spirits of victims of historical injustice; Return Flight is the Twilight-Zone-ish story of an airline pilot haunted by a past he never actually experienced; and A Woman Sobbing is a proto-feminist ghost story reminiscent of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s famous short story The Yellow Wallpaper. Supernatural (1977), on the other hand, harks back to the 19th Century literary tradition of horror, with each story told as a supposedly true narrative by someone wanting to be accepted into the exclusive Club of the Damned, an honour only granted if the teller is capable of genuinely scaring the jaded members (falling short in this results in the teller’s death). All but one episode were written by series creator Robert Muller (the exception being Viktoria, by Sue Lake) and they range from ghosts to werewolves to vampires and possessed dolls. None are particularly frightening, but they all have the comfortable chill of stories told by candlelight in front of a warm fire.

*

Although not a ghost story, Robin Redbreast, written for the Play For Today drama stream by John Bowen (who also wrote A Woman Sobbing) and directed by James MacTaggart, belongs to a related tradition which deals with lingering traces of the pagan past impinging on the lives of modern, rational people (to which, among others, belong Val Lewton’s The Seventh Victim, Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby, Tom Tryon’s Harvest Home, and Robin Hardy and Anthony Shaffer’s The Wicker Man). In this case, as the tradition dictates, Norah Palmer (Anna Cropper), a professional woman from London who moves to a remote country cottage to get over a recently ended relationship, encounters people in the village who seem vaguely hostile to the outsider, and whose habits and beliefs are somewhat alien to her. Mrs Vigo, the housekeeper who comes in to clean the cottage, seems more than intrusive (among other things, insisting on dragging the reluctant Norah to church), and Fisher (Bernard Hepton), a local man who takes an interest in the newcomer, is an amateur archeologist who can frequently be seen observing her. On their first encounter, he asks her if she’s found anything of interest as she digs in her garden; as he tells Norah, “I’m a student of that, in my own time. Old things generally.” And soon after, she finds an object on the windowsill outside her kitchen – a child’s marble cut neatly in half – and, curious, takes it inside.

As is usual with this type of story, there are a series of small, odd portents barely noticed by Norah, if at all, but which create a vague sense of unease in the viewer. This unease becomes erotic in nature when Norah comes across a young man exercising almost naked in the woods; it turns out that Rob (Andrew Bradford) works in the grounds of the local manor and can do little jobs for Norah. She’s attracted to him physically, but when she invites him over for an evening, expecting a bit of casual sex, he bores her to tears with his talk of the Third Reich. Having got rid of him, she’s frightened by an intruder and Rob suddenly turns up again and in her heightened, agitated state they do go to bed together. Disconcertingly, Norah finds herself pregnant, torn between the convenience of an abortion and a tentative desire for the child. What she eventually discovers about the situation she has been drawn into, and the fate of Rob and her unborn child, comes straight from James George Frazer’s The Golden Bough (echoed three years later in The Wicker Man); but the chilling conclusion of the story leaves her stronger and with a renewed sense of purpose and meaning.

The BFI’s region 2 DVD presents the only surviving version of Robin Redbreast, a black and white 16mm record of the originally colour production. Given the nature of colour video recording in 1970, this may not be much of a loss. The early scenes between Norah and her jaded London friends Madge (Amanda Walker) and Jake (Julian Holloway) have the stagey video look typical of British TV drama at the time, but once the story shifts to the country, with its combination of filmed exteriors and taped interiors, it becomes more cinematic. The disk includes a brief interview with John Bowen about the script’s origins – it was actually shot in and around his own country cottage – and a brief documentary on the English village, Around the Village Green, made in 1937 and co-directed by John Grierson’s younger sister Marion; it deals with the survival of older aspects of country life as the modern world encroaches.

Comments