Ghosts of Television Past, part two

While some of the films and plays in the series of disks I wrote about last week, devoted to ghost and horror stories made for British television, reveal the budgetary and technical limitations of their time and medium (low budget sets, somewhat coarse and murky video recording), the BFI has lavished its attention on one particular show from 1979. Leslie Megahey’s Schalcken the Painter, adapted from a story by J.S. LeFanu, was, like Jonathan Miller’s Whistle and I’ll Come To You, made for the BBC arts program Omnibus (and perhaps more justifiably so). Shot by John Hooper on 16mm film rather than videotape, it has a lushly colourful look which deliberately and effectively emulates the use of light, perspective and composition in 17th Century Flemish painting which is so crucial to the story. Although Peter Greenaway had been making experimental shorts since the early ’60s, it’s tempting to see the influence of Schalcken on The Draughtsman’s Contract (1982) and many of his subsequent explorations of art on film.

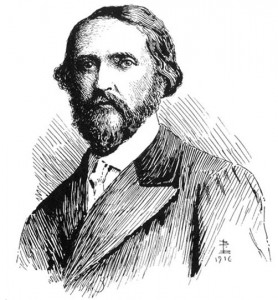

Joseph Sheridan LeFanu

I think I first encountered Joseph Sheridan LeFanu through Dover Books, one of my favourite publishers back in the late ’60s and ’70s. Dover reprinted a lot of classic literature in very sturdily bound softcover editions and I used to mail order stacks of their titles, particularly 19th Century mysteries and ghost stories. Although I never managed to get through them, I still treasure my Dover editions of G.W.M. Reynolds’ Wagner the Wehr-Wolf and James Malcolm Rymer’s Varney the Vampire, with their sometimes crude, often garish period illustrations; two of the best-known Victorian penny-dreadfuls, they were major sources of vampire and werewolf lore in literature. But one of the most important volumes I got from Dover was Best Ghost Stories of J.S. LeFanu, the heart of which is a series of novellas featuring an occult investigator named Dr Hesselius.

The most famous of these is Carmilla, the finest vampire story of the century and an influence on Bram Stoker’s later unwieldy epic, Dracula. The subtle sexual overtones of LeFanu’s narrative have attracted many filmmakers, starting with Carl Th. Dreyer, whose 1932 Vampyr was loosely based on the story. A couple of decades after Dreyer’s artful film, with censorship weakening, more commercially-minded filmmakers couldn’t resist the lure of the story’s underlying lesbianism – Blood and Roses (1960, Roger Vadim); Hammer Films’ Karnstein trilogy – The Vampire Lovers (1970, Roy Ward Baker), Lust For a Vampire (1971, Jimmy Sangster), Twins of Evil (1971, John Hough); Daughters of Darkness (1971, Harry Kumel); The Velvet Vampire (1971, Stephanie Rothman, with a vampire named Diane LeFanu); The Blood-Spattered Bride (1972, Vicente Aranda); Alucarda (1977, Juan Lopez Moctezuma). And yet, despite the obvious appeal of this one story, LeFanu remains much less well-known than his contemporaries Dickens and Wilkie Collins.

Very few of his other works have been filmed; the BBC in particular has always shown a preference for the tales of M.R. James right up to a version of The Tractate Middoth adapted and directed my Mark Gatiss just this past year. There was a 1947 feature based on the novel Uncle Silas (The Inheritance, starring Jean Simmons) and ITV’s Mystery and Imagination series from the mid-’60s did adapt three of LeFanu’s stories; but since then there have been few other attempts.

Schalcken the Painter (Leslie Megahey, 1979)

Below: the painting invented by LeFanu

So I was intrigued when the BFI announced that they would be releasing a Blu-ray edition of Schalcken the Painter as part of their Flipside line. Schalken is a relatively short story about a Flemish painter who loses the woman he loves to a ghostly suitor. What I didn’t know until I got the disk was that LeFanu had based the story on a real painter, Godfried Schalcken (1643-1706), and that the painting at the centre of the story, as described by the author, bears a strong resemblance to many of the actual painter’s canvasses. In the story, Schalcken (Jeremy Clyde) is the student of Gerrit Dou (Maurice Denham), whose niece Rose Velderkaust (Cheryl Kennedy) he falls in love with. But a very wealthy and decidedly sinister nobleman named Vanderhausen (John Justin) appears and makes a deal with Dou for Rose’s hand – and then vanishes with the girl. In LeFanu’s version, the implication is that this figure is a statue from the cathedral in Rotterdam which came to life after seeing the girl one day and has taken her away to some other reality. The painting in the story is an expression of Schalcken’s horror at discovering the fate of the girl he loved.

Megahey’s adaptation sticks very closely to the original in most ways, but I confess that the first time I watched it (having just re-read the story in preparation), I was vaguely disappointed; the director tones down the most distinctly horrific elements of the story – in particular the climactic catastrophe after Rose reappears briefly many years later, a scene which is rendered very briefly in the film. But on a second viewing, it becomes clear that Megahey is using the story for other purposes, that in fact it is a meditation on a particular period of art history in which the ghost story is used to illustrate some harsh truths about the practice of painting in a society which has come to define itself almost exclusively in commercial terms.

Money dominates the story. Dou, who is almost blind after years of painting, spends a lot of time counting his takings by candlelight – fees for paintings, fees from his students. Schalcken, doggedly determined if not inspired, has ambitions to become a wealthy painter himself, but at present he has no money and thus can’t even tell Rose about his feelings for her. When the grim Vanderhausen arrives with his offer of a chest full of gold, Dou can see no way to refuse; the man has the money, the sale must be agreed to. Devastated, Rose pleads with Schalcken to run away with her, to spare her the horrifying prospect of marriage to what looks like an animated corpse. But he has no money; the best he can promise is that after he establishes himself and makes his fortune, he will “buy back the marriage contract” and he leaves her to her fate.

Below: The Temptation of St Anthony

After her disappearance, Rose seems all but forgotten by Dou and Schalcken. The student does become successful (though resentful that he still can’t command the same fees as his master), but even as his art becomes more proficient and he gains wealth, he’s haunted by Rose’s absence and his personal paintings (as opposed to commissions) are full of signs of guilt and regret. Here Megahey pushes LeFanu’s narrative conceit with surprisingly convincing force. Schalcken’s paintings, of which we are shown many, are full of haunted figures, the suggestion of erotic connections always mediated by material considerations – jewels, money – and all cast in dark, candlelit spaces in which shadows crowd around the figures. The artist, motivated so strongly by material desires, embeds finance in every situation. And Schalcken searches endlessly in brothels, in transactions with prostitutes, for some trace of the feeling he once felt for Rose.

Many years later, when she returns one night, terrified, bruised and disheveled, pleading with him not to leave her alone, not to allow death to return and claim her … he fails her again, losing her forever. Visiting the church where she was married he has a vision, a dream, or perhaps a genuine experience of the supernatural, in which he traces her to a crypt where he witnesses her coupling with the lifeless corpse of her husband, sex joined with death in a rebuke of Schalcken’s failure to choose life over money.

Virtually every image in Schalcken the Painter evokes a Flemish painting (one witty moment gives us a brief glimpse of Rembrandt, referencing one of his famous self-portraits – a cameo by Charles Stewart, whom I rented a room from in North London in 1975; strangely, this is the second time in the past year I’ve been surprised by his appearance in a movie, the first being in Alan Birkinshaw’s Killer’s Moon); the film is visually gorgeous … but all those images are framed in terms of commercial intentions and financial transactions; the richness of the art becomes its own critique. The story is narrated in LeFanu’s voice (often using words directly from the text), read by the distinctive Charles Gray with a consistent tone of ironic detachment which grows more chilling as what it calmly describes becomes more horrific. Megahey has managed to achieve a remarkable balance between an illuminating lecture on art history and a depiction of the human failings of the artist whose work can provide such aesthetic pleasure.

It’s interesting to note how much more care the BBC was willing to lavish on arts-related programs like Omnibus (the home not only of this and Miller’s Whistle and I’ll Come To You, but also of several of Ken Russell’s richly idiosyncratic biographies of composers and artists in the ’60s) compared to the more limited resources provided to the Christmas ghost stories. When Megahey first proposed Schalcken to the BBC, the head of music and arts programming actually wanted to give it to Lawrence Gordon Clark (director of all but one of those Christmas stories), but Megahey held onto it until he was put in charge of Omnibus a few years later and immediately commissioned himself to make the film. Perhaps only in the strange environment of the BBC back in those days could such a distinctively odd hybrid of melodrama, horror, biography and history have emerged, seamlessly blending fact and fiction to produce rich insights into the practice of art. And now thanks to the BFI’s Flipside, Schalcken the Painter can be seen not just as a landmark television production, but as a remarkable film in its own right, and one of the finest disk releases of the past year.

The Blu-ray also includes a couple of other ambitious short films – The Pit (1962), an experimental Poe adaptation by Edward Abraham, and The Pledge (1981), Digby Rumsey’s adaptation of a story by Lord Dunsany about a gang of highwaymen rescuing the decaying corpse of their confederate from a gallows on a wind-blown moor.

There’s also an informative 39-minute interview with Megahey and cameraman John Hooper.

Comments