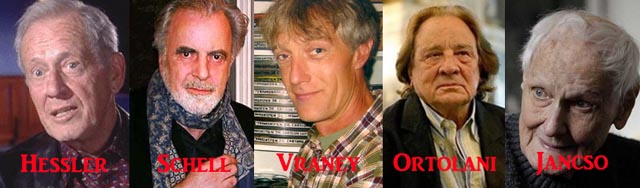

Miklós Jancsó … and others: RIP

Word of Philip Seymour Hoffman’s untimely (and possibly drug related) death earlier today comes quickly after news of the (more timely) deaths of three European giants. Yesterday, award-winning Austrian actor Maximilian Schell died at age 83 in Innsbruck. The day before, the influential Hungarian filmmaker Miklós Jancsó died at 92, and just over a week before that, Italian film composer Riz Ortolani died in Rome. He was 87.

Maximilian Schell, who grew up displaced by the Nazis (his family fled Austria when Germany took over the country in 1938, and took refuge in Switzerland), was an international star, often cast ironically as German military officers – from The Young Lions in 1958 to Cross of Iron and A Bridge Too Far in the late ’70s. But he won his Oscar playing Hans Rolfe, defence attorney for some of the Nazis on trial in Stanley Kramer’s Judgement At Nuremburg, arguing that all Germans shared collective guilt for the Holocaust. He also wrote and/or directed a number of films.

Miklós Jancsó was one of a number of East European directors who mastered the technique of long, complex shots which emphasized the duration of time and the physical presence of location as integral aspects of subjective experience; but where Andrei Tarkovsky used this technique more often to create internal, introspective states, Jancsó’s aim was to embody visually the flow of history and the movement of human beings within that flow. His films eventually became so formally abstract that the question of individual psychology and character became irrelevant, but in his earlier work there’s a fierce examination of the tension between ordinary people’s lives and the relentless social and historical forces which shape and – all too often – destroy them.

Riz Ortolani probably did as much to define the sound and tone of popular Italian cinema as the more widely known Ennio Morricone, but Ortolani approached movies from a different angle. His work is less eccentric than Morricone’s – often lyrical and melodic, jazz inflected, at times falling deeply into a laid-back lounge style. What was strikingly original was the way he would apply this to material which visually contradicted the music. The harsh brutality of films like Ruggero Deodato’s Cannibal Holocaust and House On the Edge of the Park, or Lucio Fulci’s Don’t Torture a Duckling is accompanied by lush, romantic tracks which make the images all the more horrific (the influence of this can be seen in film’s like Alex Cox’s Walker, in which a battle/massacre is accompanied by a light, melodic piece composed by Joe Strummer which is the only sound heard over the bloody visuals). Despite Ortolani’s long and prolific career (between film and television work, he wrote and/or conducted almost three hundred scores), it’s both annoying and illuminating to note the somewhat backhanded obituary by Bruce Weber in the New York Times, which refers to “dozens” of scores rather than hundreds, and overall takes a slightly condescending and dismissive tone: the only work of real significance apparently was More, his theme for Jacopetti and Prosperi’s Mondo Cane which, with lyrics later added, became a much-covered pop song – including a version by Sinatra, accompanied by Count Basie and his orchestra. Despite that track’s success (it was nominated for an Oscar), Ortolani only sporadically worked on English and American movies, the majority of his work being in Italian film and television. This post gathers together a fairly representative selection of tracks available on YouTube.

On a less lofty plane, Gordon Hessler also died a couple of weeks ago at age 83. Hessler got his start working on Alfred Hitchcock Presents in the mid-’50s and eventually started directing in the early ’60s. His credits, a mix of features and television, are generally undistinguished, but for a brief period from 1969 to 1973 he turned out several stylish if somewhat confused horror/fantasy movies, starting with the Corman-Poe imitation The Oblong Box and ending with Ray Harryhausen’s The Golden Voyage of Sinbad. Although Murders In the Rue Morgue and Cry of the Banshee offer some striking visuals, neither rises to the level of Corman’s AIP movies, but the bizarre Scream and Scream Again (1970) is well worth a look; seemingly stitched together from various disparate genre body parts, it combines sci-fi and horror with a paranoid political thriller set against a Swinging Sixties background. The barely coherent, patchwork script by Christopher Wicking (based on a novel by pulp hack Peter Saxon) seems to leave Hessler free to construct scenes with a sense of freedom and energy which is often lacking in his other work.

And finally, on January 2, Mike Vraney, the founder of Something Weird Video, died at 56. Something Weird is something like the anti-Criterion, dedicated to digging up and preserving the least reputable (and often least competent) dregs of exploitation cinema. Most of my Andy Milligan disks are SWV releases. Few companies have dared to offer such vast quantities of over-ripe cheese, but my fondness for Something Weird goes back to a ragged rental copy of John Parker’s brilliant expressionist oddity Daughter of Horror (aka Dementia)[1], first seen sometime in the late ’80s or early ’90s and remaining to this day one of my favourite films.

_______________________________________________________________

(1.) 05-02-2015 Well, this is embarrassing: it turns out that that VHS tape was from Sinister Cinema, not Something Weird … still, SW has fed my appetite for trash over the years.

Comments