Reading Movie History

It’s easy to feel overwhelmed by the sheer amount of writing about film that’s available on the Internet these days. You can instantly find dozens if not hundreds of reviews of any new movie the moment it’s released. Back in the day, of course, the average viewer had much more limited access to reviews; the local paper, weekly news magazines, monthly specialty journals. Paradoxically, this could be more useful to a movie-goer than today’s flood. You’d get to know individual critics, their tastes, the ways in which they formulated their opinions – even people you disagreed with could be useful in helping you decide what to go and see. Now, it’s much harder to judge whether or not a particular review is any use to an individual viewer, so many of us tend to take a quick look at Rotten Tomatoes or Metacritic, skim the brief excerpts and glance at the aggregate score … and as often as not pre-form an opinion based on this very tenuous evidence. It’s a little disturbing to note that a lot of commenters on these sites tend to get hostile or contemptuous of reviewers who disagree with the predominant consensus, as if opinion isn’t a personal, individual thing, but something which is socially defined and imposed.

That said, there is nonetheless a lot of good writing on-line, if not sufficient time to read it all. Being an old guy who evolved in the pre-Internet world, I haven’t fully adapted to the new environment and often find myself retreating back to print, to the primitive hard-copy world of books. As interesting and entertaining as John McElwee’s Greenbriar Picture Shows blog is, I waited until he published Showmen, Sell It Hot! last year before getting a more sustained sense of the breadth and depth of his ongoing examination of the history of movie marketing. And Thomas Doherty’s Hollywood and Hitler provided a fascinating perspective on the intersection of business, politics and morality in a world plunging ever deeper into chaos through his careful analysis of the Hollywood studios’ responses to the rise of fascism throughout the ’30s.

But perhaps more valuably, in the past year I’ve been going back into the history of film criticism, to contemporary reviews of often long-forgotten movies as well as those which eventually evolved into classics despite mixed or negative receptions when they were first released. This is something like delving into primary sources, discovering opinions formed when what we now find so familiar was still fresh and new. It’s a way of opening cracks in received opinion; decades of writing about film from a historical perspective have made the art’s history seem like a coherent movement through various periods of innovation, social pressure, adherence to accepted tastes and aggressive assaults on same … but reading contemporary reviews reveals just how ad hoc that history was much of the time, being built moment by moment under numerous different pressures – largely political and economic, but also the constantly evolving ideas of what was socially acceptable (someone who has grown up on Saw and Hostel would find it incomprehensible that there could have been widespread and heated controversy about the violence of Public Enemy and Little Caesar, or that audiences were genuinely terrified by Tod Browning’s Dracula and James Whale’s Frankenstein).

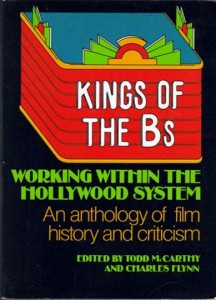

In reading both American Film Criticism and Farber On Film from the Library of America, Stanley Kauffmann’s Figures of Light, and most recently Agee On Film, one of the most interesting things I’ve discovered is that serious critics and reviewers back in the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s frequently treated minor B and genre movies with respect. And yet by the ’70s, when academic film studies had begun to establish themselves, Charles Flynn, in his introduction to the seminal Kings of the Bs (co-edited with Todd McCarthy), worked very strenuously to justify the effort to examine (and take seriously) these kinds of films and the people who made them. In fact, his efforts to justify paying critical attention to “trash” are so strenuous that he becomes irritating; jabs at current critical standards, and the films they support, seem deliberate provocations; his dismissal of Kubrick as both kitsch and morally dangerous seem glib rather than illuminating, and not very helpful in asking that respect be given to Edgar G. Ulmer and Joseph H. Lewis, among many others. This introduction (though not many of the essays, articles and interviews in the book) dates Kings of the Bs. Genre studies and critical attention to obscure/minor filmmakers have since become mainstream and we no longer need to set up dubious either/or comparisons … after all, at their base, critical positions have always rested and still rest ultimately on the individual critic’s taste and personal experience of individual films.

Manny Farber famously set “termite” art (work which established opinion might view as crude, trivial, embarrassing – say, the films of Sam Fuller) against “white elephant” art (bloated works designed to prove the seriousness of an establishment craving respect). Agee repeatedly praised the films of Val Lewton and his collaborators, small B movies seen by their studio (RKO) as program filler – an attitude which worked to Lewton’s advantage because no one in the front office gave a damn what he was up to as long as he turned a profit.

Agee’s method is initially quite disconcerting. He’ll spend the first half of a review praising a film for what it accomplishes and how it accomplishes it, and then abruptly switch to detailing everything that makes it a wretched failure, forcing you to go back and take another look at why you thought he was giving it such a positive review. He gets passionate and often quite angry when he sees a film and its makers falling short of their potential – but the potential he sees is some kind of Platonic ideal of a perfect film. Being far less stringent than Agee, I tend to err on the side of making allowances for those failures of technique and imagination which mar otherwise excellent movies.[1]

What seems common to most of the writers I’ve been reading is a (sometimes gloomy) belief that the best days of the movies are already over, that crudeness of sensibility and an increasing reliance on technical effects and the slickness which can be bought with bigger budgets have cheapened the art and replaced genuine creativity and moral and intellectual depth with clever, facile displays of “style”. (Yes, that means you, Orson Welles, with your Citizen Kane.) In the early ’40s, Agee repeatedly asserted that Hollywood had been in decline for more than a decade (in effect, since the arrival of sound); in the ’60s, Kauffmann was often irritated by the “cleverness” of the generation which emerged from live television in the ’50s (John Frankenheimer, Arthur Penn, et al).

Both Agee and Farber devoted a lot of space to non-fiction films made during the war – “record films” as Agee called them. And both critics praised the films coming out of Britain and Russia (and in Farber’s case, from the National Film Board in Canada) at the expense of the work coming out of the US war department – recognizing an authenticity bred of immediate personal experience of the war, rather than the sanitized propaganda being produced for the American home front. (Although Agee reserves special praise for John Huston’s Battle of San Pietro and Let There Be Light, the latter shamefully suppressed by the government.) For Agee, there was too often a lack of commitment to reality, as opposed to the technique of “realism” – he perceived a poetic sense of genuine realism in, for instance, Val Lewton’s Curse of the Cat People, a film attuned to the rich psychological states of childhood. He responded very positively to the post-war trend of shooting out in the world, on location, as opposed to the studio, no matter how finely detailed the sets might be.

This concept of realism/reality has always been very unstable. Agee had great admiration for Rossellini’s Rome Open City and for the astute use of non-professional actors in the years immediately after the war; Kauffmann had an irritated dislike of “cinema verite” or “direct cinema” in the ’60s, seeing the movement as a bit of a con, filmmakers using sleight-of-hand to conceal their heavily manipulated constructions of supposedly unmediated reality (he included the Maysles Brothers and Frederick Wiseman in this), and yet had undiluted praise for Allan King’s Warrendale for its apparent unmediated presentation of reality … establishing and holding critical precepts can be a tricky business!

While Agee often wrote about a particular film in terms which addressed intent and effect while remaining vague about actual content (in many of his reviews, the reader gets little if any sense of the story or the characters), one thing which stands out in a lot of this older writing is the casual way in which the critic talks openly about important plot details, giving away critical moments, even endings, as they discuss issues arising from the film. We’re so conditioned today with an almost pathological concern with “spoilers” that this can become almost disorienting.

Yet, looking back to my own early experience of film and the development of my own sense of film history, I know that I often read about particular movies long before I ever got to see them, and that this reading sometimes supplied every important detail of stories, themes, characters, style. But it never occurred to me at the time that anything was being “spoiled”. I knew all about Norman Bates and his mother long before I finally got to see Psycho – both from reading about the movie in various books and from having read Robert Bloch’s original novel – but none of this diminished the experience of the movie itself, as I became so caught up in the movement of the story and the carefully constructed atmosphere. And in fact, I can still enjoy and appreciate the film even though I’ve seen it many times (the last time, digitally projected on a big screen, it had a freshness of impact which was all the more surprising because I believed it had become so familiar for me that I was expecting merely a ritual reiteration of an old experience).

Of course, if the concept of “spoilers” were truly rooted in the way we experience art and entertainment, we would never want to see anything more than once. So why has it taken such a firm hold in recent years? Partly, I suspect, because of the sheer volume of chatter that we’re now subjected to. In the past, knowing details of a story might actually pique one’s interest; now the risk is that hearing those details repeated endlessly in the media and on-line has the adverse effect of destroying our interest. (I know I’ve had the experience numerous times of seeing the initial teaser trailer for a new movie and having my interest aroused, only to have that interest crushed by longer and more revealing trailers as the release date approaches, to the point where, when the movie finally opens, I no longer have any desire to see it.)

But still, my interest in a particular movie is unlikely to reside in some singular event in the plot. The pleasures of a film like Psycho don’t reside in the surprise revelation, but in the way the story is constructed and performed. This is true of all lasting movies, ones we turn to repeatedly … so the obsession today with spoilers indicates a shift in our relationship with the movies and perhaps more importantly with the way films are made, the commercial intentions of the corporations, the reduction of mainstream movie-making to sensation rather than substance (and substance doesn’t necessarily mean weighty thematic depths; it can be a richness of story and character that engages the viewer beyond the revelatory plot points – has anybody ever not wanted to see The Maltese Falcon again because they now know [spoiler alert!] the black bird is a fake?).

Kauffmann addressed this point in his generally favourable review of Easy Rider in 1969:

As for that ending, which I had better not reveal, it is a coup de theatre that tries to consummate the sanctification of the two youths, but after the shock is over, it is seen as only a coup de theatre. Which is why I won’t describe it. But when a critic can’t describe an action for fear of spoiling it for a prospective viewer, that is a pretty fair index of the action’s superficiality.

I think this also speaks to the essence of the critic’s role. Too much of what gets written about movies today is absorbed into the process of marketing the industry’s product, the need to sell it to the consumer. This is why ratings have become so ubiquitous, the assigning of one to five stars or whatever, giving the reader all he or she needs to know at a glance (why even bother to read the words when the show only got one star?). But genuine criticism, the kind of writing Agee and Farber and Kauffmann were deeply involved in, forms one side of a dialogue with the reader, demanding an actively engaged response. This is why, back in the day, I could read with pleasure critics whose opinions I often disagreed with completely. But that disagreement would serve to sharpen my own thoughts about a movie. Unlike so many of the commenters on Rotten Tomatoes, I wasn’t just looking for confirmation and reinforcement of my own fixed opinion – I wanted the movies I saw to be alive with the potential to surprise me, and the critics I read were there to keep my responses alert and open to change. (Many of Agee’s sharp criticisms of favourite movies – such as Carol Reed’s Odd Man Out or Powell and Pressburger’s Black Narcissus – are apt and valid. But that doesn’t diminish my feelings about those movies, merely forces me to acknowledge flaws which I was essentially already aware of but perhaps had not been inclined to examine in any depth; after all, perfection would leave no space for us to engage with a movie, but would merely require that we sit back and passively admire it.)

One final, and rather important, thing to note about these critics is that they were all real writers; that is, they were all skillful users of language and their reviews are often a pleasure to read regardless of what they might be writing about. Agee in particular had a devastatingly sharp wit which not infrequently makes me laugh out loud as I read. A few samples at random: In John Ford’s Fort Apache “there is enough Irish comedy to make me wish Cromwell had done a more thorough job.” “Mel Torme reminds me of something in a jar but is, unfortunately, less quiet.” “Wilson is by no means the first film in which one might watch Hollywood hopping around on one foot, trying to put on long pants.” “This is just the same old toothless dog biting the same old legless man.” “The Miracle of the Bells. As pernicious a gobbet of pseudo-religious asafetida as I have been forced to sniff at, man and Sunday-school-boy. I hereby declare myself the founding father of a Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to God.” (Although I should note that the quality of Agee’s reviews for Time is often considerably lower than in those for The Nation; there’s an air of writing down to a more “common” audience, and an irritating use of jargon – in one column alone he uses “cinemice”, “cinemaddict” and “cinemagician” – which is painfully grating.)

Some of the best reviews I’ve read in the past year have been of long-forgotten movies which I’ve never seen and perhaps will never see. But reading about them may sharpen my responses to familiar films which I return to for yet another viewing or to other movies which I will see for the first time in the future.

_____________________________________________________

(1.) There’s a particularly striking example of Agee’s approach in a long piece he wrote for The Nation in September 1948, shortly after the death of D.W. Griffith. He praises Griffith as essentially unequaled in the power of his imagery and as, yes, pretty much the inventor of every facet of the art of film. But then he elaborates on Griffith’s weaknesses, the clinging to elements of 19th Century stage melodrama, a propensity for excessive sentimentality, and so on. Most strikingly, however, Agee mounts an angry defence of Griffith against the charges of racism which had been laid against The Birth of a Nation since its initial release. In so much of his writing, Agee reveals a fierce intelligence about social and political issues in the movies he’s reviewing, but here, in speaking of Griffith’s portrayal of Blacks as marauding rapists and, most egregiously, as gibbering monkeys in the legislature scenes, Agee claims that Griffith was bending over backwards to be fair to Blacks and had succeeded in creating an accurate picture of post-Civil War conditions. For once, it appears that what he liked about a filmmaker had clouded his ability to see clearly what there was not to like in the work. (return)

Comments