Styles of Horror, part two

… et mourir de plaisir (1960)

A few weeks ago Glenn Erickson reviewed a German DVD edition of Roger Vadim’s … et mourir de plaisir (1960, aka Blood and Roses), the first of many modern erotic adaptations of J. Sheridan LeFanu’s Carmilla (the actual first, and most artful, adaptation was Dreyer’s Vampyr [1932]). This is a movie I’ve known about for more than forty years, having read about it and seen stills in numerous books on horror and vampire cinema since the late ’60s. Although it was often written about in negative terms – and Glenn’s review is also fairly conflicted – I had to see it and tracked down a copy at Diabolik DVD, which arrived gratifyingly quickly.

Despite all I’d read over the years, I no doubt had unrealistically high expectations, largely due to those stills I’d seen in books and magazines. And definitely the greatest asset of the film is Claude Renoir’s rich widescreen photography. In fact, the heightened use of colour, particularly in the night scenes of Carmilla, dressed in a flowing white gown, drifting dreamily around the Karnstein estate, are startlingly reminiscent of Mario Bava’s work. Indeed, Vadim’s film is reminiscent of Bava in other ways, not least a storyline with similarities to Bava’s first feature, Black Sunday, which was released just a month before … et mourir de plaisir, and an overall oneiric tone similar to Bava’s Lisa and the Devil.

Vadim maintains ambiguity throughout the film about whether or not events are genuinely supernatural or simply a matter of deranged psychology. Count Leopoldo de Karnstein (Mel Ferrer) is about to marry Georgia Monteverdi (Elsa Martinelli), apparently oblivious of the obvious attraction his cousin Carmilla (Annette Vadim) feels for him. We quickly learn that the Karnsteins were suspected of vampirism in the 1600s, with the family crypt violently desecrated by the locals. In her attraction to Leo and jealousy of Georgia, Carmilla comes to identify with her ancestor Millarca (whose portrait she strongly resembles). When an explosion opens an old family tomb, Carmilla is either possessed by Millarca or believes she’s been possessed. Believing herself to be a vampire, she seeks Georgia as a victim, her jealousy mutating into an erotic attraction. But despite the lush colours of the film’s imagery, the sexual subtext remains muted and the film ends up being a little dull where it could have used some of the overheated excess of Vadim’s Metzengerstein segment of Spirits of the Dead (1967).

Although not entirely successful, … et mourir de plaisir in retrospect seems to have had a fairly strong influence on Euro-horror in the ’60s, with its blend of the Gothic and the modern, its striving for a kind of subtle artiness (as in many of Bava’s films, in Harry Kumel’s Daughters of Darkness, the vampire films of Jean Rollin, even some of the early films of Jess Franco) rather than gross shocks, and the suggestion of eroticism which would explode later in the decade, often in movies based to some degree on LeFanu’s story. (Note: Tim Lucas adds an interesting footnote to the background of Vadim’s movie in a Video WatchBlog post from May 17, 2016, found here.)

In comparison, the Hammer films of the period and the parallel work being done by Roger Corman in the States seem more conventional and old-fashioned.

*

The Vincent Price Collection (1960-72)

The choices made by Shout Factory for their Vincent Price Collection Blu-ray set seem a little random. Instead of providing a complete set of the Corman-Price-Poe films, it omits Tales of Terror, The Raven and Tomb of Ligeia, but supplements four Corman films with Robert Fuest’s The Abominable Dr Phibes (but not the sequel) and Michael Reeves’ Witchfinder General, the latter two tonally very different from the Corman films – Fuest’s is much campier, Reeves’ much grimmer.

But the set does provide attractive transfers of all six films and an array of extras which offer an appreciative overview of Price’s mid-career success as a horror icon, acknowledging the element of camp which often crept into his work while also honouring the strength and range of his performances in many of these movies. In Fall of the House of Usher (which appears to be the same transfer as Arrow’s excellent region B edition), Price takes full advantage of the opportunity given to him by Corman and scriptwriter Richard Matheson, perhaps presenting American teens with their first glimpse of a kind of perverse decadence which Hollywood might not have been able to convey in anything other than the adaptation of a literary classic. The immediate follow-up to Usher, The Pit and the Pendulum, attempted to repeat a successful formula, but seems less fresh, with Matheson overloading the narrative with complications – premature burial once again, scheming wives, hereditary evil and madness – to fill in the time before getting to the title horrors.

In the three years after Usher, Corman made thirteen features, four of which were at least nominally adapted from Poe, and he was feeling rather bored with the famous author (The Raven was played as broad comedy), so in 1963 he convinced Sam Arkoff and James Nicholson at American-International to back the first ever adaptation of an H.P. Lovecraft story. The Haunted Palace was based on one of the author’s longer pieces, The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, but by the time it was released AIP had tagged it as another Poe adaptation (including a brief quote from one of Poe’s poems as justification). The Haunted Palace has obvious affinities with the Poe films – the period setting, the Gothic atmosphere – but it has a darker tone with its small New England town beset by a century-old curse which leaves many of the children born there as pathetic and occasionally murderous mutants. Price’s Charles Dexter Ward is possessed by the spirit of his warlock ancestor Joseph Curwen, who having been burned alive by the townsfolk is somewhat ill-tempered and determined to awaken Lovecraft’s Elder Gods to lay waste to the world. Much of the film deals with the decay of Ward’s marriage as he swings back and forth between himself and his evil ancestor. The strongest element of the film is the struggle of Ward’s wife Ann (Debra Paget) to comprehend the increasingly radical and violent changes in her husband – and all this was invented by scriptwriter Charles Beaumont (there’s no wife in the story) – making Haunted Palace one of the strongest collaborations between Corman and Price.

It was immediately after The Haunted Palace that Corman relocated to England, where his budgets seemed to stretch a little further, permitting a larger scale for his final two Poe films. The best known is The Masque of the Red Death (1964), essentially a medieval morality play about a sadistic, debauched count (Price, of course) who retreats into his castle with his sycophantic hangers-on when plague spreads across the countryside. In some ways, this is Corman’s most pretentious film, borrowing heavily from Bergman and dressing the horror with various layers of symbolism. Working with cinematographer Nicolas Roeg, Corman went all out with the rich colour scheme of the film (though to my eye, Shout! Factory’s transfer is far too bright, stripping the visuals of any nuance, and for the most part giving the large sets a flat television-like look). Prince Prospero’s perverse games are like a restrained dress rehearsal for Pasolini’s Salo, with a similar sense of disgust about what people are capable of doing to each other.

It’s a pity that the set omits Corman’s final Poe film, The Tomb of Ligeia, which at least for my taste is a better film than Masque. But in lieu of that, we get Dr. Phibes, a deliberately campy art deco black comedy about a disfigured madman who sets out to kill the medical team he holds responsible for his wife’s death, his chosen method the Biblical plagues which were inflicted on Egypt. The film has a rich look and a certain amount of invention in the methods of murder, but Price is masked throughout and stripped of his voice, and the set-pieces have a rather mechanical air of repetition. The plot was essentially used again in Douglas Hickox’s much more successful Theatre of Blood two years later.

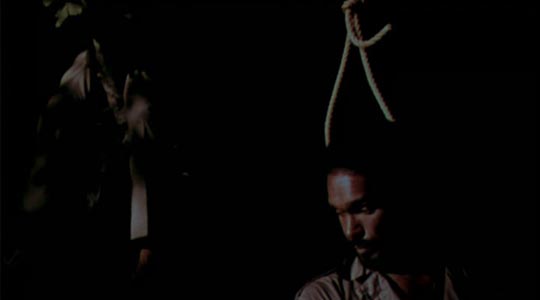

It took me years and multiple viewings to come around to the generally held view that Michael Reeves’ third and final film, Witchfinder General, is something of a minor masterpiece. I’m not sure now why I was initially so resistant to it. A bleak story based on some historical reality, it follows with relentless logic the spread of violent madness through a society which has lost all stability (in this case, England during the civil war), which permits criminal opportunists to wreak havoc for their own profit. Shot in rural Norfolk, the film makes fine use of the picturesque countryside as a backdrop for torture, murder, hangings and burnings, eventually driving its pair of young lovers to the brink of madness and over… The tension between Reeves and Price is now legendary, but there’s no denying that the young director (he was only 25 when he made the film, just before his death) managed to torment the camp tendencies out of his star, making this Price’s grimmest and most realistic performance in a horror film.

*

Ganja & Hess (Bill Gunn, 1973)

Bill Gunn was a writer and actor who worked hard to change the ways African-Americans were portrayed in popular culture. The same year (1970) that he scripted Hal Ashby’s first feature, The Landlord, and a Bernard Malamud adaptation for Czech director Jan Kadar, he wrote and directed his own first feature, Stop, a story of marital stress and wife-swapping. But it was three years later that he made his second and most famous film, Ganja & Hess (1973). Given money by a company called Kelly/Jordan Enterprises to make a blaxploitation vampire movie, Gunn came up with something very different. Which apparently didn’t please his backers; they radically re-cut the film into a more linear, exploitable horror movie called Blood Couple and Ganja & Hess sank out of sight, becoming one of the most sought-after “lost” films. In 1998, David Kalat’s All Day Entertainment managed to piece together most of the original cut for release on DVD – the original negative had been cut for the producer’s version, so the transfer used a number of 35mm prints. In 2006, All Day released a “complete” version which reinserted a three-minute sequence sourced from a 16mm print; needless to say, the DVD didn’t supply a pristine image and the soundtrack was somewhat noisy. The new Kino Blu-ray is cleaner and brighter, but still very grainy, with a fairly weak soundtrack.

Gunn’s original script (included on both DVD and BD versions as a PDF) was quite linear, with an opening section heavy on exposition. This material was shot (and apparently used in the producer’s cut), but in the editing (by Gunn and Victor Kanefsky) it was all jettisoned. Gunn’s version opens with an elliptical, allusive, fractured montage of images and sounds which are on first viewing (and even on subsequent viewings) confusing. In a feature on the All Day DVD, David Kalat parses this opening to reveal how Gunn actually laid in all the backstory quickly, but in ways not easily graspable by a casual viewer; crucial information is imparted by two song fragments by Sam Waymon, who wrote the score as well as playing the Reverend Luther Williams, who works part time for Dr. Hess Green (Duane Jones, star of Night of the Living Dead). We get glimpses of the reverend preaching at his gospel church while in a voice over he explains Hess Green’s affliction – immortality and an addiction to blood (the word vampire is never mentioned in the film). The source of this addiction is an ancient curse (tied in the song fragments to pre-Christian Africa as well as to Christianity itself with Christ’s exhortation to his followers to eat his flesh and drink his blood [communion]). The curse, however, stems from Hess’ being stabbed with an ancient Myrthian ritual knife … but that event takes place about a third of the way through the film, so the reverend’s narration is completely displaced in narrative time. This refusal to play by standard rules is what gives Ganja & Hess its distinctive oneiric tone, and makes watching the film both exhilarating and frustrating.

A further point which separates Gunn’s film from the mainstream of ’70s blaxploitation is that the characters are wealthy, educated, erudite professionals – Hess lives in a mansion in the country, not in the inner city; at a garden party Hess converses with his young son in French. The only time issues of race intrude into the film is during a night scene in which Hess’ new assistant Meda (played by Gunn himself) is drunk and contemplating suicide in the grounds of the mansion; Hess points out that a dead black man on the property would cause him a great deal of trouble with his white neighbours and the police. It’s not long after this that Meda stabs Hess with the knife and then commits suicide – this act of violence is what transforms Hess, injecting a wild primitive element into his tightly buttoned-down personality.

Hess struggles with his addiction, something which disgusts him, and eventually seeks some kind of salvation in the gospel church. What this all means in terms of history, religion, and personal psychology remains somewhat obscure, but the film works on an almost subliminal level to create an aura of meaning, a suggestion of the weight of ancient cultural, racial and spiritual forces bearing down on contemporary characters. And the images are often strikingly beautiful, while the performances of Jones, Gunn and Marlene Clark (as Meda’s widow Ganja, who initially imposes on Hess and eventually marries him) are far richer and more authentic than you’d find in the kind of genre film Gunn was working against (and which his producers thought they were paying for).

The Blu-ray carries over all the extras from the All Day DVD except for that discussion of the opening by Kalat. These features include an excellent group commentary by Marlene Clark, cinematographer James Hinton, producer Chis Schultz and Sam Waymon; a half-hour documentary of a post-screening Q&A, intercut with interview clips with Schultz and editor Victor Kanefsky from the time of the original DVD release; and PDFs of the script and an article by Tim Lucas and David Walker about the history of the film.

Comments