Criterion Blu-ray review: Hearts and Minds (1973)

Three things are immediately apparent when re-watching Peter Davis’ documentary Hearts and Minds some forty years after it was made. One, it retains the power to evoke a strong sense of anger and outrage in the viewer. Two, despite having been made during the final stages of the U.S. war in Vietnam, it has a remarkable clarity about the history and conduct of that misbegotten adventure and its perspective remains undated. And three, it is chilling to realize that the lessons so sharply drawn in the film have been discarded and forgotten by a nation which seems prone to make those bad decisions over and over again.

And yet, in some ways, Hearts and Minds is a difficult film to write about as film. It’s exceedingly well-made, dense with information, rich in emotional experience, and constructed with such assurance that the viewer takes it in without necessarily being consciously aware of the craft which went into its making. But to speak of the powerful photography (largely the work of Richard Pearce), the resonant and nuanced editing (Lynzee Klingman and Susan Martin) and the revealing interviews (Davis’ extensive experience in television news having prepared him for getting the most out of his subjects, even when they might have been suspicious of his motives), while all deserve praise, risks diverting attention from the subject of the documentary itself. This is one of those cases where content becomes paramount and the craft involved serves the experience being dissected by the filmmaker; which is to say, that as fine as the film is, the viewer is engaged more by the material than the aesthetic accomplishment.

And so, in writing about Hearts and Minds, one finds oneself writing about Vietnam and the history of the war rather than about the film as film.

Although Davis began the project with a rather broad idea of where he was going, he eventually chose to focus on U.S. participants both at a policy level and in the military, some of whom eventually turned against the war while others remained committed to it. The title comes from a speech by President Johnson about the necessity of winning the “hearts and minds” of the Vietnamese people, but Davis’ subject is the hearts and minds of Americans, an investigation into not simply what happened, but how it had come about and what the consequences were for those involved.

He quickly sketches in the origins of the war in the calamity of France’s post-WW2 attempt to reassert colonial power in Southeast Asia. A French diplomat asserts that John Foster Dulles had actually offered France a couple of atomic bombs to put an end to their war, which was clearly an anti-colonial war of independence. President Eisenhower was surprisingly blunt in stating that what was at stake was western access to valuable natural resources which might be endangered by an independent state. By the time the French were ignominiously defeated at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, the U.S. was paying most of the costs of that war. Following French defeat, free elections were scheduled, but the U.S. wasn’t confident that the “right” people would win, and thus set in power the first of a series of puppet dictators who would serve U.S. interests.

With Vietnamese nationalism balking at U.S. dominance as much as it previously had at the French (and as it had for more than a thousand years against various powerful neighbours, particularly China), resistance to U.S. interests wouldn’t go away and gradually America was sucked deeper into a hopeless situation. Apart from business interests, with the Cold War in full swing the “domino principle” was subscribed to by most of those in charge in the States, the idea that if Vietnam fell to a communist government (which current doctrine insisted must be imposed from outside and not a genuinely indigenous force), then the rest of Asia would be “lost” to the West. The irony is that during the ’50s, the nationalist leader Ho Chi Minh had written repeatedly to the American government asking for assistance because he believed that a nation which had won its own independence from a despotic foreign government must be on the side of the Vietnamese people with their own aspirations to independence. As more than one of Davis’ interview subjects points out, the U.S. found itself fighting on the wrong side.

What was clear in retrospect was that the U.S. enterprise was doomed to fail. And the more that fact became obvious, the more ferocious the American assault became in a futile attempt to prove U.S. superiority to this backward peasant country. Ultimately, the U.S. dropped more bombs on Vietnam than every country in every theatre of World War 2 combined, and sprayed 100 million pounds of toxic chemicals which destroyed vast swathes of forest and agricultural land, poisoning countless Vietnamese civilians (and U.S. soldiers) in what remains the worst instance of chemical warfare in history. But none of this succeeded in fulfilling either the overt purpose of “defeating” the Vietnamese or the implicit purpose of proving U.S. military superiority over any potential enemies.

With all of this as background, Hearts and Minds concentrates on the personal experiences and opinions of a wide range of people – politicians, high-ranking military figures, soldiers and pilots and prisoners of war – who delineate all the moral and psychological conflicts engendered by the war in Americans who had grown up (during and after World War 2) in the sure and certain knowledge that they lived in the best country in the world, a country predicated on freedom and justice, a country whose intentions were always open and honest as it fought against the evils of totalitarianism. Some of these interview subjects were driven more deeply into their certainties by the war, while others found their most fundamental beliefs shattered.

But Davis is careful not to turn the film into nothing but a lament for American suffering. Throughout, he provides glimpses of the Vietnamese and what they went through under the American assault, speaking to ordinary people whose lives were destroyed by American bombs, who were tortured by the puppet governments imposed by the U.S., and who speak eloquently about themselves and their country, giving the lie to the blatantly racist attitudes underlying U.S. behaviour, which dismissed these people as primitive and savage and so much less than those who had come to “civilize” them.

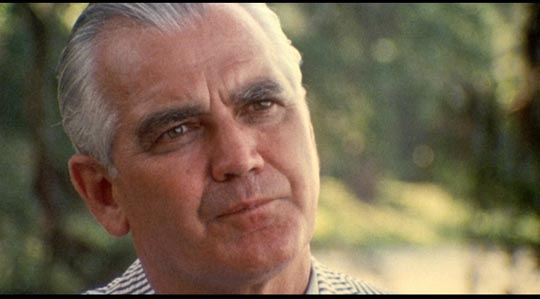

These strands of the film come together in the most chilling (and controversial) moment in which General William Westmoreland, commander of U.S. forces from 1964 to 1968, states with calm certainty that Asians “don’t value human life” the way we civilized westerners do, a comment juxtaposed with the terrible emotional pain of Vietnamese civilians burying their own war dead. This institutional dehumanization is what enabled the U.S. to continue its ultimately futile war for so long.

Westmoreland eventually sought a court injunction to prevent release of the film because, he said, he had been “misrepresented”. However, it’s hard to imagine in what context his calm dismissal of the humanity of “Asians” would seem reasonable. In fact, that attitude was widely held both among the military stationed in Vietnam and by people back home in the States. At one point, Davis shows an American Independence celebration in which a man in Revolutionary era costume proudly talks about the fight to throw off British oppression, and then angrily dismisses the idea that the Vietnamese could in any way be compared with that noble history.

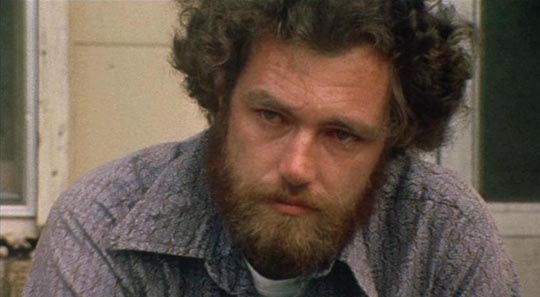

One of the great strengths of Hearts and Minds lies in its ability to reveal the full humanity of the Vietnamese through moving interviews with civilians who put themselves at risk by speaking to the camera: among them Mui Duc Giang, a man making coffins for children killed in raids; Nguyen Thi Sau, a woman almost crippled and blinded in a South Vietnamese prison for merely expressing opposition to the war – and in the eloquence of former soldiers like Captain Randy Floyd who, having flown 98 missions without seeing or thinking about the people he was dropping bombs on, finally realized the awful human cost of what had seemed a proud technical achievement. Late in the film he breaks down as he talks about thinking of his own children on the receiving end of those missions and the sense of identity he had come to feel for the civilians on the ground.

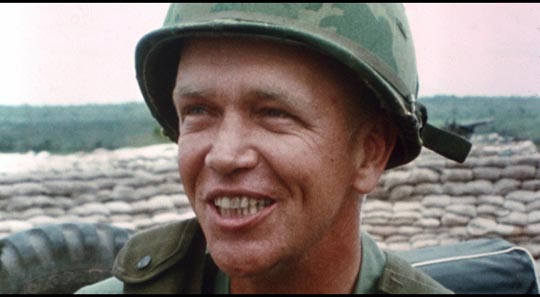

But Davis is careful to allow the expression of opposite opinions, not in some mechanical attempt to provide “balance”, but rather to present a richer and more disturbing picture of the country’s state of mind. Woven through the film is the story of Lieutenant George Coker, who returns to the States after seven years as a prisoner of war, his mindset remaining where it was when he first went to fight, his years of isolation leaving him untouched by all the social turmoil resulting from the anti-war movement. He speaks to a large welcoming crowd in his hometown, to a group of grade school kids, and finally to a group of mothers, to whom he gives credit for the spirit of the American fighting man. Unlike Randy Floyd and the seriously injured Robert Muller, Coker doesn’t question the rightness of the war; he’s proud of what he did to help his country “fight communism”. When asked by one of the schoolkids what Vietnam was like, he replies that it’s a beautiful country except for the people. He describes flying bombing missions as an exhilarating technical exercise and unlike Floyd has never seen the effects of his work on the people far below his plane. And yet he’s a quiet-spoken, thoughtful man who can’t even find it in himself to be angry at anti-war protesters or even deserters and draft-dodgers.

Davis’ film is consistently nuanced throughout, made without didactic insistence, and continually encouraging viewers to think and form opinions of their own. Although it was accused of being anti-American, it actually finds things to admire in many of its subjects; but it is unequivocally anti-war, or perhaps more accurately pro-humanity. Whatever else has been learned in the decades since the end of the Vietnam War, Hearts and Minds remains the single clearest depiction of the nature of that conflict and Criterion’s Blu-ray edition offers a superb presentation of the film itself and a rich collection of supplements which expand on the production as well as the context of the war.

*

The disk

Criterion has released Hearts and Minds in a dual-format edition (a practice they are unfortunately discontinuing in September), with the film and all supplements available in both formats. The 1.85:1 image has been transferred from a restored 35mm interpositive and, despite the mix of original footage and archival material, the picture is consistently bright and finely detailed, belying the conditions under which much of it was shot. The original mono soundtrack, also restored and cleaned up, is also excellent.

The supplements

In terms of the film’s production, the key supplement is the commentary track originally recorded for the 2001 DVD release. Davis fills in a lot of detail about how the film came about, and the importance of support from Bert Schneider, one of the partners at BBS, the production company responsible for Easy Rider, Five Easy Pieces and so on. Davis also gives full credit to the work of cinematographer Richard Pearce and editors Lynzee Klingman and Susan Martin. Given that the track was recorded in 2001, before 9/11 and the subsequent wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, Davis’ final words about the American tendency to get into conflicts for confused reasons, without understanding the places the nation chooses to attack, seem doubly chilling now.

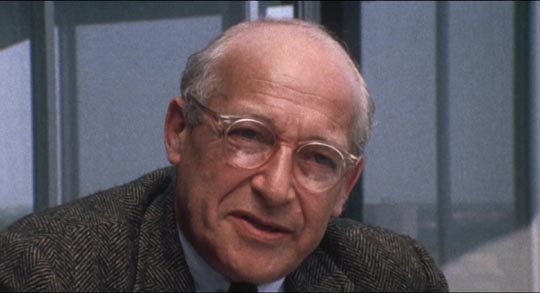

In addition to the commentary, the disk includes two-and-a-half hours of unused interview material drawn from the 200 hours of footage shot for the production. Four of these segments are with people not in the film itself, who were consistently against the war at the time (and so ultimately didn’t fit into the film’s scheme); the other two are additional clips from General Westmoreland (26:14) and former presidential adviser (JFK and LBJ) Walt Rostow (24:22), who remained confirmed hawks who considered that the U.S. could have won if only it had been willing to commit fully to the war rather than holding back(!).

The four anti-war voices are: French journalist and historian Philippe Devillers (10:53), who points out that both France and the U.S. never came to terms with the fact that Vietnamese nationalism was a struggle against colonial oppression. Former Undersecretary of State (JFK and LBJ) George Ball (19:30), who consistently argued against U.S. involvement in Vietnam, but refers to the war as a “mistake” and asserts that LBJ was intensely concerned about sparing civilians; he adds that the U.S. had no territorial ambitions and was simply trying to stop aggression by the communists. Tony Russo (34:21) was a RAND Corporation researcher whose experience interrogating Vietnamese prisoners led him to the conviction that “the enemy” were in fact fighting for their own independence, that the U.S. was on the wrong side; realizing that his country couldn’t admit a mistake and change course voluntarily, he joined with his colleague Daniel Ellsberg to release the Pentagon Papers, which went a long way towards finally turning public opinion decisively against the war. David Brinkley (23:49), network news anchor, talks about the impact of televising the war in a relatively uncensored way and the shock that seeing the grim details on the nightly news had on a population for whom war had always been a distant and sanitized thing.

In addition, there are two brief deleted sequences, a funeral in a South Vietnamese village accidentally bombed by U.S. planes (5:23) and raw footage of severely injured South Vietnamese soldiers in Cong Hoa Hospital (2:52).

The thick booklet included in the dual-format set contains five essays, four of which were originally included with the 2001 DVD edition, by critic Judith Crist and historians Robert K. Brigham, George C. Herring and Ngo Vinh Long. Finally, the booklet reprints an essay by Peter Davis originally written in 2000 (and updated here) in which he talks about the political and psychological consequences of the defeat in Vietnam.

Comments