Jodorowsky’s Dune: the triumph of imagination

Alejandro Jodorowsky’s adaptation of Dune has one significant advantage over David Lynch’s attempt to tame Frank Herbert’s large and unwieldy novel: it never got made. It was never undone by studio interference, by almost impossible logistical problems, by the sheer difficulty of transferring a complex text from page to screen. And thus, Jodo’s Dune remains a wonder of the filmmaker’s imagination and survives now as possibly the most amazing film which never got made.

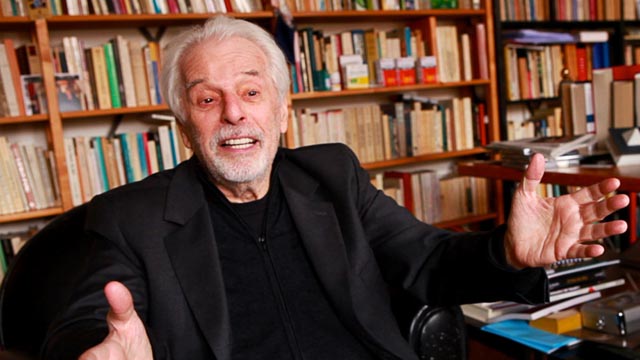

That film, or rather its conception, is the subject of Frank Pavich’s remarkable documentary Jodorowsky’s Dune; this tightly constructed film, built around wonderful interviews with the 84-year-old Jodorowsky and supported by other interviews with key people involved in the project, not only provides a lively account of the three years in the mid-’70s when the director and his French producer, Michel Seydoux, put together one of the most ambitious and original productions of its era; it also, through the use of elaborate storyboards and production art, gives us a glimpse of the film Jodorowsky had in his head …

Even four decades later, it’s easy to see how Jodorowsky gathered such a remarkable team around himself – he sparkles with wit and humour and a passion for creative work. By his account, he approached the project by instinct (he hadn’t even read the book when he proposed making the film) and various key personnel crossed his path through uncanny synchronicity as the project gathered momentum. There was French graphic artist Moebius (Jean Giraud), who undertook the monumental task of creating a detailed storyboard for the entire film. Then English illustrator Chris Foss was roped in after Jodorowsky saw a number of his covers for science fiction novels. The Swiss artist H.R. Giger was drawn in and, after Jodorowsky had an unsatisfactory meeting with Douglas Trumbull in Los Angeles, Dan O’Bannon was tapped as special effects supervisor on the strength of the ultra-low-budget Dark Star. Foss, Giger and (in an archival audio interview) O’Bannon all attest to Jodorowsky’s infectious energy and the way in which he tapped into each of his collaborators’ strengths.

The planning resulted in a remarkably detailed film-on-paper; the massive book which the producers put together with storyboards and designs to present to various studios as they looked for funding, of which apparently only two copies now exist, is the source of the animated visuals Pavich uses to show us various scenes from the film (anyone seeing this documentary will long to lay hands on the volume … it looks like an ideal object for someone like Taschen to publish, a perfect companion for their exhaustive edition of Kubrick’s unfilmed Napoleon). By all accounts, those Hollywood executives were all hugely impressed by the presentation … and yet all of them turned the project down (Seydoux claims that the team just needed an additional $5,000,000 to complete the budget).

But, given the nature of the business, it’s hardly surprising that the suits balked. They liked the presentation … but not the director. Despite the fact that he was the one who had pulled it all together. From their perspective, here was a driven man, a madman in fact, who clearly risked being uncontrollable. A man who viewed his mission as the creation of a work of art, a man who would not warp that work to suit the demands of less creative businessmen who, because of their positions in the corporate structure, were compelled to demand a degree of subservience from the filmmakers they backed.

(I clearly recall Universal sending people down to Mexico to start stripping pages out of Lynch’s script in an attempt to rein in the schedule and budget, while Lynch was surreptitiously writing new scenes to add in – perhaps a subversive way to counter the oppressive interference of head office, but already a sign of defeat …)

The key distinguishing characteristic of Jodorowsky’s Dune, taking its cue from the tone of Jodorowsky’s interviews, is a sense of humour, an appreciation of details which are often almost absurd (Jodorowsky’s strategies for getting Salvador Dali to play the Emperor and Orson Welles to play Baron Harkonnen). Jodorowsky seems to take a great deal of pleasure from contemplating the creative effort he put into the project, and only towards the end does a suggestion of bitterness enter in when he talks about darker feelings towards those who want to tether creativity and rein in vision.

There are three main stages to the making of a movie: pre-production, shooting, and post-production. Pre-production in turn has two phases – planning and conceptualization, and the physical process of building sets, creating wardrobe and props, and so on. Jodorowsky’s Dune remained at the purest stage, conceptualization, and thus escaped all the infinite compromises which are the practical burden of filmmaking. Without the inevitable interference of the studio executives and their minions, this movie exists now only as a kind of Platonic ideal.

Jodorowsky speaks of some resentment towards the De Laurentiis production which superseded his, and finally went to see Lynch’s film only after his son Brontis (whom he had cast as Paul Atreides) insisted. As if reliving the experience, Jodorowsky’s features become lighter and happier as he speaks of his growing awareness that Lynch’s film was a disaster[1], that the people who had taken his dream away from him had failed. But he doesn’t blame Lynch. What he saw on screen was the effect of those studio suits crushing an artist’s vision.

Would Jodorowsky’s Dune have been the radical, paradigm-shifting movie its would-be makers envisioned? With Dali as the Emperor, Welles as the Baron, David Carradine as Duke Leto, Mick Jagger as Feyd … would it have been a vast, hallucinatory experience or a gigantic folly? An irrelevant question, because it now exists only on the level of imagination and there it remains as a masterpiece, a work of such originality and imaginative power that it has, paradoxically, influenced countless movies since. After all, it was Jodorowsky who introduced designer Chris Foss and artists Moebius and Giger to filmmaking – all of whom went on to transform the science fiction genre through their work on Alien and numerous other films.

Frank Pavich’s documentary is a unique depiction of the creative process which lies behind movie-making. Its sense of Jodorowsky’s conception is so strong, and so skillfully pieced together, that it enables the audience to see in their imagination the film that Dune might have been, rather than (as in, say, Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe’s Lost In La Mancha [2002]) the sad wreckage of a director’s failed intentions. In the end, Jodorowsky’s Dune is an exhilarating and inspiring ode to the fundamental drive which underlies all movie-making, the need to express and create, which so often falls short in the execution and yet so often also bounces back for another try. In the making of the documentary, Jodorowsky and Seydoux reconnected after many years and together have now made the director’s first feature in twenty-three years – the well-received autobiographical La danza de la realidad, a phantasmagoric account of Jodo’s own childhood and the roots of his filmmaking.

_________________________________________________________________

(1.) I, of course, have a less harsh opinion about Lynch’s Dune. (return)

Comments