Arrow Video, part three: Runaway Train (1985)

This is my 300th post in 45 months, something which I find both surprising and daunting. Looking back, I’m not sure how I’ve kept up this kind of schedule … and I must confess that I’m not sure that I’ll be able to maintain such an output: I recently started a full-time job, while still trying to complete a one-hour documentary I’ve been working on since January, so the past few weeks it’s been more difficult to find the time and energy to write (and I’ve been a bit discouraged by the tapering off of review copies since the spring, particularly the non-appearance of several titles I’d really been looking forward to). But after almost four continuously productive years, I’ve become somewhat addicted – the idea of slacking off makes me feel anxious – so while I may have to slow down a bit, I can’t imagine stopping altogether …

Donald Cammell was just one of many filmmakers who made their way to Hollywood throughout the movies’ first century. Producers, directors, writers, technicians and actors too numerous to count, from England and various parts of Europe (in particular Germany), helped to build the place and shape what global audiences expected from the movies. Some were more successful than others; some stayed, others merely passed through, although the decision to remain was not necessarily rooted in success. While figures like Alfred Hitchcock and Billy Wilder were central to Hollywood’s identity and sense of itself, others like Edgar G. Ulmer toiled at the fringes, eking out a precarious existence while doing the thing they loved to do with little recognition (at least, at the time they were doing it). But Hollywood, despite its twin temptations of industrial infrastructure and seemingly endless supplies of money, was not always a good fit, even for filmmakers who were already successful before they arrived – just look at the way John Woo was unable to make anything there like his great Hong Kong thrillers, with their excess of operatic visual style and theatrical emotions; American naturalism reined him in and whenever he tossed in a visual note like a melancholy memory of his Chinese work (all those shots of doves) western audiences tended to laugh rather than see poetry.

Five years after the release of his four-and-a-half hour epic meditation on his homeland, Siberiade (1979), Russian filmmaker Andrei Konchalovsky made a movie in Pennsylvania starring Nastassja Kinski and John Savage called Maria’s Lovers, about two people dealing with the emotional and psychological consequences of wartime trauma. Five years later, he made Homer and Eddie (a comedy about a mentally handicapped man and a sociopathic woman, starring Whoopi Goldberg and James Belushi) and the Sylvester Stallone/Kurt Russell cop buddy movie Tango and Cash. In between, there were three other movies, one of which was a masterpiece (ironically financed by Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus’ notoriously crass Cannon Group).

Runaway Train (1985)

Runaway Train was based on a screenplay originally written by Akira Kurosawa, rewritten by Paul Zindel and Edward Bunker, and although it might at first seem to threaten to topple over into allegory about out-of-control lives, Konchalovsky’s direction, Alan Hume’s cinematography, and especially the three key performances by Jon Voight, Eric Roberts and Rebecca De Mornay, keep it grounded, the sheer physical presence of the film (reminiscent of Friedkin’s Sorcerer) providing a fertile base for its exploration of character within a style of poetic realism.

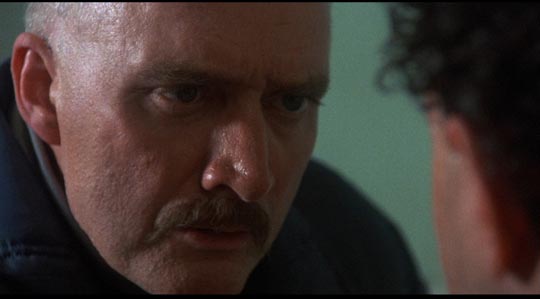

The film begins in an archetypally brutal prison in the wilds of Alaska where lifer Manny (Jon Voight) is the special target of sadistic Warden Ranken (John P. Ryan). Freed by the courts after three years welded into a solitary cell, Manny knows that it’s only a matter of time before Ranken finds a way to kill him. With the help of his friend Jonah (co-writer Edward Bunker, himself a former convict), Manny escapes through the prison sewers with younger, hero-worshipping prisoner Buck (Eric Roberts) tagging along. Manny has no patience for Buck, who can barely keep up with him as they cross a snowy wasteland and make their way to some rail yards. Manny chooses the train he wants to escape on; but as it starts to roll the driver dies of a heart attack, leaving the throttle wide open. As the railroad controllers try to figure out a way to stop the runaway, the antagonism between Manny and Buck gradually evolves, with Manny’s anger and contempt gradually turning to a kind of weary pity as he sees his younger self in Buck, knowing the hopeless future the younger man faces.

That’s when a young female railway worker, Sara (Rebecca De Mornay), turns up. She’d been napping when the engine started to roll and is the only one to realize just how dire their situation is. Her presence shifts the terms of the relationship between Manny and Buck yet again. With the train heading onto a dead-end spur as Ranken closes in in a search helicopter, Manny sees the possibility of some kind of redemption in sacrificing himself for Buck’s survival …

Runaway Train is raw and intense, the physical danger on the train (superbly evoked in a seamless mix of location shooting and remarkable studio work) paralleling the almost uncontrollable violence in the two men. Both Voight and Roberts were nominated for Academy Awards for what was the best work of both actors’ careers. Rebecca De Mornay, also never better, remarkably holds her own against the two stars, providing a human counterpoint to their savage animalistic energy.

It’s interesting to compare Runaway Train with a more recent movie which shares a surprising number of narrative details with it. Tony Scott’s rousing Unstoppable, the late director’s final movie and one of his best, is also about a runaway train and two men who begin at odds with one another but gain mutual respect as they undergo their ordeal. There are numerous moments which seem undeniably influenced by the earlier film – the other train forced onto a siding as the runaway races towards it, smashing the final few wagons; the attempt to land a man on the engine by helicopter which goes terribly wrong; the harrowing attempt to climb along the outside of the speeding engine – but the decent working class guys of Unstoppable are more conventional protagonists with conventional backstories used to draw on audience sympathies.[1]

Manny and Buck are something more primal, more archetypal; men stripped of social connections, reduced to the level of pure animal survival. They have no ties, nothing to easily evoke those viewer sympathies. But as the film progresses and we come to understand the pain and hopelessness that drives them, that makes them strike out furiously at a world which has discarded them as worthless, and as Manny gradually comes to feel something for Buck, this monster of rage becomes more recognizably human and the final image of him facing the cold unsympathetic universe gives him a dignity and stature that’s paradoxically exhilarating.

Everything about Runaway Train – the look, the narrative tone, the treatment of character – seems to cut against the grain of mainstream Hollywood entertainment. Most of the negative comments about the film on IMDb complain about “bad acting”, unsympathetic characters, “stupid story” – that is, about all the elements that deviate from the Hollywood standard; comments by people who have accepted those standards as the norm, who expect a movie to reflect a particular definition of narrative reality, people who – sadly, it seems to me – don’t see that this is about storytelling and that stories don’t need to be slavishly bound by some common definition of “realism”. (Realism as a set of stylistic tropes is no more valid as a storytelling choice than fantasy or surrealism or whatever other set of rules an artist might decide to use; what really matters is the internal dynamics of a particular work, whether it plays honestly and effectively by its own rules.) Runaway Train might be better compared to ancient sagas with their heightened emotions and the larger-than-life actions of flawed heroes. And somehow Konchalovsky managed to use the resources of the Hollywood machine to create this, a movie which possesses a distinct and powerful Russian flavour. It’s no wonder the people at Cannon couldn’t figure out how to sell the film effectively; they were used to Chuck Norris action movies and here was this magnificently bleak existential parable built around fierce and broken characters. Despite the Oscar nominations (three, including one for editing), the film grossed less than its $9-million budget in the States.

Arrow’s Blu-ray (in a dual-format edition) is a spectacular improvement over the old MGM DVD from 1998; the hi-def transfer faithfully captures the textures of the wintry landscapes and the train itself. Although there’s no making-of documentary on the disk, there are four interview featurettes which provide interesting insights into the production, starting with Konchalovsky himself (15:57), who speaks of being pretty much left alone by Cannon to do whatever he wanted. Jon Voight (37:49) and Eric Roberts (16:02) speak of their different experiences with the Russian filmmaker (reflected in Konchalovsky’s remarks about the two actors); Voight apparently got along really well with the director, with shared creative and intellectual perspectives on the material, while Roberts was more antagonistic, finding the Russian difficult and pretentious. The final interview is with Kyle T. Heffner (17:04), who played the technician who had installed the control system which is used to try to manage and stop the train’s progress.

The accompanying booklet includes not only a fine essay by Michael Brooke and an interview with production designer Stephen Marsh, but also a reprint of the 1963 Life magazine article which formed the basis of Kurosawa’s original script.

__________________________________________________________________

(1.) There are also strong visual echoes of Runaway Train in Bong Joon-ho’s recent sci-fi movie Snowpiercer (2013). (return)

Comments

6 2/3 a month…one every 4.5 days.

If you want to be really pedantic, you could say that works out to one post every 108 hours!