Arrow Video, part two: White of the Eye (1987)

In retrospect, the strange career of Scottish director Donald Cammell seems to hinge on an inexplicable decision to relocate to Hollywood in the 1970s. Beginning as an artist in full ’50s-’60s Bohemian mode in Paris and London, he turned to film first as a writer – though it’s difficult to gauge his talents from the initial results: Duffy (Robert Parrish, 1968) and The Touchables (Robert Freeman, also 1968). With his next project, Cammell decided he wanted to direct it himself, but when the brilliant cinematographer Nic Roeg, who was approached to photograph the film, said that he was now more interested in directing than shooting, Cammell suggested they direct it together. The result, Performance (1970), had a very troubled gestation which dragged on for a couple of years, with Roeg moving on to other things as Cammell struggled to complete the film his way against resistance and even hostility from his backers.

One of the key British films of the ’60s, Performance embodies both the liberating social and cultural changes of the time and the collapse which inevitably followed the dismantling of the moribund remnants of Imperial Britain. Stylistically, the film remains quite radical, although its rapid hallucinatory editing style has long since been absorbed into the mainstream; what remains fresh is its polymorphously perverse view of the social and aesthetic construction of identity and its implications for the unstable foundations of capitalist consumer society.

Despite the fact that Roeg left the project long before completion, following disagreements with Cammell about the direction the film had taken, as time passed it became generally assumed that Roeg was the true director – largely because Roeg, ironically, absorbed so many of Cammell’s editing techniques into his own subsequent work. The fragmentary, allusive, non-linear style pretty much defined Roeg’s work throughout the ’70s and ’80s, from Walkabout (1971) to Track 29 (1988). This misapprehension is no doubt rooted in the fact that Roeg’s work is so well known, while Cammell struggled to get anything made at all, with only three more features in the quarter century following Performance, before he committed suicide in Hollywood in 1996 at age 62.

Although I had read about Performance for years I didn’t finally see it (on home video) until sometime in the ’80s, so my first encounter with Cammell was Demon Seed in 1977, a film which apparently was compromised by producer interference and was definitely not well received at the time. Despite the reviews, I loved it. I was predisposed to like pretty much anything science fictional back then (this was on the cusp before George Lucas did so much to return the genre to kids’ amusement with Star Wars [released seven weeks after Cammell’s film]), and Demon Seed was visually imaginative, with a story strongly rooted in character. The idea of artificial intelligence has a long history in the genre, most often focused on power-mad computers bent on taking control of their human creators. Of course, a lot of those movies were cheesy B-movie fun, but the theme had previously been treated seriously by Kubrick in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Joseph Sargent in Colossus: The Forbin Project (1970).

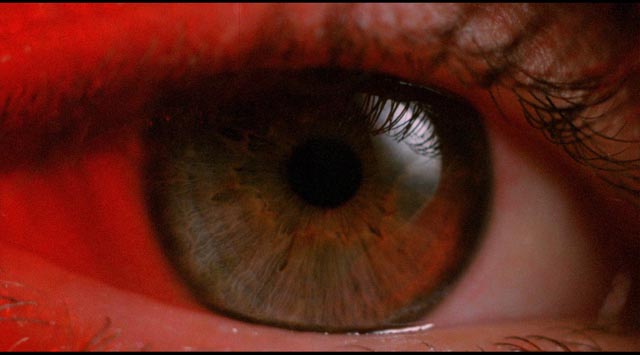

Demon Seed, adapted by Robert Jaffe and Roger O. Hirson from a potboiler paperback by the prolific Dean R. Koontz, was different from those earlier iterations, however. While the story was conceived as a slice of horror-porn about a computer which commits rape, Cammell kept elements of the horror, but turned it into something more intelligent and thoughtful. Yes, it’s about a super computer which achieves sentience and traps its creator’s wife in her fully automated house in order to impregnate her; but ultimately it’s about the imperative of an intelligent being to achieve life and, despite the harrowing process it puts the woman through, the movie ends on a positive, even hopeful, note. (Yes, despite the detached, clinical intentions of Proteus, the machine does indeed commit rape, but even here Cammell complicates the problematic material; both the computer [voice of Robert Vaughan] and Susan Harris [Julie Christie] are such well-drawn characters that their conflict, and the complex emotional relationship which evolves from it, constantly work against a simple reading.) In the film’s final image, the child to which the woman has given birth opens its eyes and rewrites a narrative moment which goes back in movies to Frankenstein (1931), and even further to The Golem (1920), in which witnesses to such a birth shout in fear and wonder “It’s alive!”, by itself calmly announcing “I’m alive.”

While there were seven years between Performance and Demon Seed, there was a whole decade before Cammell managed to get another project through the Hollywood mill. Which makes it all the odder that he clung to the idea that Hollywood was the place he had to be to make movies. As rocky as the British industry was in the ’70s and ’80s, might he not have had a better chance back there? Impossible to answer. His third feature, White of the Eye (1987), fared even more poorly than Demon Seed on a commercial level, while his final film, Wild Side (1995), was so compromised by producers who were pretty much looking for soft core porn that Cammell took his name off it (it’s credited to “Franklin Brauner”). Both of these movies have points of interest, though neither fulfills the considerable promise of Performance.

*

White of the Eye (1987)

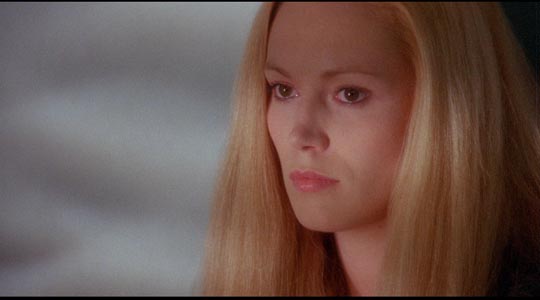

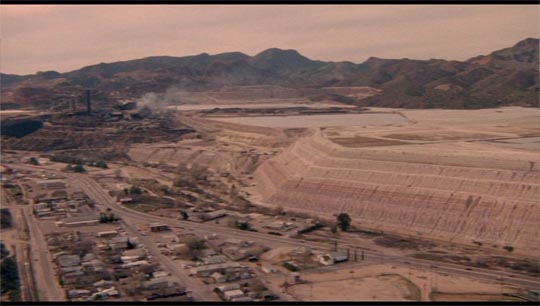

White of the Eye, scripted by Cammell and his wife China Kong, was based on a novel written by libertarian mystery/thriller writer Andrew Klavan (writing, with his brother Laurence, as Margaret Tracy). The story of a serial killer in an Arizona town, it contains elements familiar from the genre – the ritualistic nature of the murders, the circumstantial evidence which seems to point to an innocent man – but its real subject is the troubled marriage of audio electronics sales and installation expert Paul White (David Keith) and his wife Joan (Cathy Moriarty), increasingly under stress because Paul can’t seem to resist the aggressive come-ons of Ann Mason (Alberta Watson), one of his customers. As the investigation of the murders draws closer to Paul (based on a set of tire tracks which link his van to one of the crime scenes), flashbacks fill in the story of the couple’s relationship; Joan and her boyfriend Mike Desantos (Alan Rosenberg) stopped off in town on their way from New York to the west coast and Paul attracted Joan away from Mike; she stayed on, married him, had a daughter … attaining a stability she hadn’t previously known, all of which is now jeopardized by Paul’s affair.

This story of a marriage, set against remarkable desert landscapes, is powerful and finely observed (gorgeously photographed by Larry McConkey, who has had a very long career as a Steadicam operator going back to Birdy [1984] and extending up to 12 Years a Slave [2013]). Cammell’s allusive editing creates an almost mystical connection between the vast barren spaces and the fraught emotional landscape of the marriage. But the mechanics of the mystery plot too often feel like a distraction, and when that element takes over in the final act, the film all but comes off the rails in a frenzy of implausible plot contrivances and overwrought action. White of the Eye becomes almost a textbook example of what happens when a filmmaker’s real interests come into conflict with the generic and commercial imperatives of the material he’s chosen to work with (chosen, no doubt, specifically for those perceived commercial possibilities).

Arrow’s Blu-ray (in a dual-format edition) is a big improvement over the previous Dutch region 2 PAL DVD in terms of picture quality, but where it really shines is in the extensive selection of supplements. Donald Cammell: The Ultimate Performance is a feature-length documentary made for British television by Kevin Macdonald and Chris Rodley which covers the director’s career from his Bohemian artist days through his struggle to make films and on to his suicide; the doc’s chief implication is that Cammell was some kind of genius who never managed to fulfill his potential, leaving unanswered the big question of why he believed that Hollywood was the best place to achieve his ambitions even though there was 25 years worth of ample evidence that he probably would have been better off somewhere else. The documentary is packed with informative interviews, not least some very engaging clips with Cammell himself, who comes across as a very thoughtful and likeable man.

There are also some brief deleted/extended scenes and a short film shot by Cammell in the desert in 1972, but only completed by his editor-collaborator Frank Mazzola in 1999. Photographed by Vilmos Szigmond, The Argument has striking imagery illustrating its allegorical narrative about creativity and the historical suppression of the female principle, drawn apparently from an unrealized feature project. There is also a selection of flashback scenes from White of the Eye demonstrating how they looked before the bleach bypass process which gives them a distinctive grainy, high contrast look in the film itself.

I haven’t listened to the commentary by Cammell’s biographer Sam Umland, but judging by his fumbling comments over the deleted scenes and the short (you can hear him turning the pages of his notes, which he reads in a dull monotone), I imagine it would be a bit of a slog; however, it’s reportedly packed with interesting information about both the director and the film.

Comments