Guest post:

A Weimar Cinema Revelation: Harbour Drift (1929), part two

In part two of his post inspired by a screening at the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, Howard Curle looks at the producer of Jenseits der Strasse/Harbour Drift (1929), Willi Munzenberg, and examines the critical reception of the film.

I was very impressed by Harbour Drift, a German film from 1929 screened at this year’s San Francisco Silent Film Festival, so I set about researching the film’s production and reception history. The lateral paths of the internet produced some interesting revelations although material on the film’s director Leo Mittler was scarce. On the other hand, in researching the film’s producer Willi Munzenberg I entered a veritable storehouse of material. Munzenberg emerges as a large personality, an important figure of leftist political culture in Berlin and Paris during the 1920s and ’30s. While probably not a creative film producer in the sense that we would now say of David Selznick or David Puttnam, Munzenberg nevertheless had considerable influence on the creative people who made Harbour Drift.

Willi Munzenberg

Munzenberg (1889-1940) first came to notice as the head of Workers International Relief, formed to raise funds for victims of the Volga region famine in 1921. According to biographer Stephen Koch in his book Double Lives – revealingly subtitled Stalin, Willi Munzenberg, and the Seduction of the Intellectuals – Munzenberg was a master at cajoling Western left-leaning intellectuals and fellow travelers into supporting progressive causes. Munzenberg also published newspapers like the Evening World (180,000 circulation) and magazines (Workers Illustrated Weekly, 350,000 circulation), operated a publishing house, and in 1922 began to distribute Soviet Union films, the most noteworthy (and profitable) of which was Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin. Film production via the Prometheus company followed. (For more on Prometheus and the films the company made, see Jan-Christopher Horak’s essay “Prometheus Film Collective 1925 – 1932” in the journal Jump Cut for December 1981.)

Although everyone who came in contact with Munzenberg was affected by his boundless energy and his commitment to the Comintern, the Kremlin-sponsored organization to promote Bolshevik ideology, there seems to be no consensus from his political contemporaries on the whole trajectory of his entrepreneurial and political career. Koch argues that he was always taking orders from the Kremlin, others paint a more ambiguous situation, including the suggestion that Munzenberg was a double agent, a circumstance that contributed to an ignominious death. Here a reader enters the still hotly-debated sphere of the anti-communist and anti-anti-communist left from the ’30s to the ’60s via figures such as the Hungarian novelist Gustav Regler, the cosmopolitan intellectual Manès Sperber, Munzenberg’s widow, Babette Gross, as well as better known figures like Arthur Koestler, the author of Darkness at Noon. In their memoirs all have a great deal to say about Munzenberg although little about his role as a film producer. [Along with the Koch biography, republished in 2005 with a useful introduction by Sam Tannenhaus, I would direct readers to another biography of Munzenberg, Sean McMeekin’s The Red Millionaire, and to Michael Scammell’s biography Koestler (2009).]

Critical Reception

As documented in Bruce Murray’s book, Film and the German Left in the Weimar Republic, Harbour Drift – or Beyond the Street as he more literally translates Jenseits der Strasse – received fairly positive reviews, both from the mainstream press and the Communist newspapers. The film however was not a popular success. The reason for this may come down to nothing more than stiff competition. A glance at the release schedule of German films recorded in Chronik des Deutschen Films (1995) by Hans von Prinzler reveals that in October 1929 when Harbour Drift was released, its competition during the same month included Lang’s Woman on the Moon, E. A.. Dupont’s Atlantic and Arnold Fanck’s mountain film, The White Hell of Pitz Palu. Quite obviously contemporary audiences then, as today, preferred spectacle to downbeat drama.

More striking in regard to the film’s subsequent obscurity are observations about the film in retrospect. The most significant are those by Siegfried Kracauer and Lotte Eisner, who both left Germany once Hitler came to power in 1933, made their way first to Paris and then to other Western cities where they established reputations as early film scholars.

Both are curiously off-handed in their remarks about Harbor Drift, which leads me to speculate that perhaps they had not seen the film for many years when they wrote about it. In From Caligari to Hitler, published in 1948, Kracauer provides a plot summary which includes a nicely poetic description of the demise of the film’s old beggar character, but he ends his one paragraph on the film by saying, “Contemporary German reviewers emphasized the Russian style of this film. Its variance with Tragedy of the Streets is as obvious as its gloominess.”[1] Kracauer admits in a footnote that his reading of the film is based on a “prospectus to the film and synopsis” from the Museum of Modern Art clipping files so it’s possible that he had not seen the film or, writing in the post-World War II period, did not have an opportunity to adjust his perspective on the film.

I thought Kracauer might have discussed Harbour Drift at the time of its initial release but I’ve not been able to find such a piece. The essays that he wrote around the time of the film’s release, translated and edited by Thomas Y. Levin under the title The Mass Ornament (Harvard, 1995), provide a fascinating portrait of Weimar Germany and anticipate a cultural analysis similar to that of Roland Barthes’s Mythologies. Moreover, an entire section of The Mass Ornament is given over to a discussion of cinema, including a whole chapter on the films of 1928, one year prior to the release of Harbour Drift, but unfortunately there is no mention of the film in the text. Admittedly, Kracauer’s tendency is to emphasize cinema as a phenomenon of modern urban leisure so it’s not surprising that individual titles are not singled out.

Eisner’s comment on Harbour Drift (under that title) comes in her study of German Expressionist film, The Haunted Screen, originally published in 1952. She thinks enough of the movie to include it in a selective filmography at the end of the volume, but only mentions it in the body of her text by way of disparaging it and another film compared, in her estimation, to one more substantial. The passage is worth quoting:

The films standing at the crossroads between the fantastic and the real, such as M, were always to have an intensity and power which films like Piel Jutzi’s Mutter Krausens Fahrt ins Gluck [Mother Krause’s Journey to Happiness] (1929), made in the Berlin streets, or Leo Mittler’s Jenseits der Strasse (1929) shot on the Hamburg docks vainly tried to equal.[2]

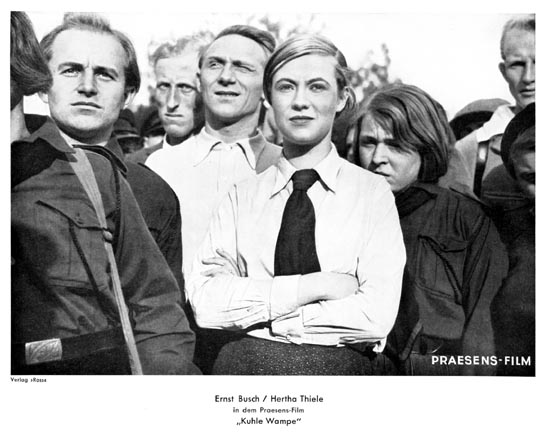

A more recent analysis of the film Kuhle Wampe (Slatan Dudow, 1932, with a screenplay by Bertolt Brecht) by Marc Silberman in the anthology Weimar Cinema: An Essential Guide to Classic Films of the Era edited by Noah Isenberg (2009) also mentions Harbour Drift. Like Kracauer and Eisner, Silberman uses the film as a counterpoint to argue the distinctiveness of Kuhle Wampe, the last film produced by Prometheus before the company claimed bankruptcy. The critical part of the argument is as follows:

In the period of crisis characterizing the last years of the Weimar Republic, the structural instability of the working class caused by unemployment and impoverishment made it particularly susceptible to middlebrow ideologies of social harmony and classless statism proposed by the National Socialists. Kuhle Wampe addresses various aspects of this issue not so much to clarify its causes but to show the powerlessness resulting from the desire to escape from politics altogether. In this respect the film differs radically from Jutzi’s melodrama and other socially critical portrayals of working-class family life, such as Leo Mittler’s 1929 Jenseits der Strasse (Harbour Drift) or Hans Tintner’s 1930 Cyankali (Cyanide), as well as from the industry’s attempts to capitalize on the effects of the depression with escapist comedies such as Wilhelm Thiele’s 1930 musical Die Drei der Tankstelle (The Three from the Filling Station).

Although Harbour Drift does deal with working class powerlessness and conveys a disengagement from politics, I think Silberman mislabels it as a portrait of working class family life. No family of the kind shown in Putzi’s or Dudow’s films exists in Mittler’s film: every character is disconnected from family. You could argue that the beggar tentatively assumes a surrogate father role to the unemployed youth, but this relationship is dashed; the landlady is never motherly towards the prostitute; even the young woman on the houseboat who smiles at the young man near the beginning seems to lack parents. The nexus that joins these characters is not familial but ultimately and ruthlessly monetary. Harbour Drift as its English release title succinctly declares, is concerned with proletarian flotsam: the film itself becomes a cultural touchstone for the Wall Street crash that happened the very month of its release and is a harbinger in its pessimism of more disasters to come. If Kuhle Wampe, as Silberman rightly argues, expresses a more authentic embodiment of working class consciousness than Mutter Krausens, and Thiele’s Filling Station represents a wish fulfillment that presages the escapist side of National Socialist cinema to come, then Harbour Drift is made of harder stuff.

Along with Pandora’s Box and maybe other films – Silberman mentions Hans Tintner’s Cyanide — Harbour Drift is a representative film of what Gustav Hartlaub termed Neue Sachlichkeit. Translated as New Objectivity, it represented an artistic sensibility of disillusionment, the source of which was Germany’s defeat in the 1914–1918 war but compounded by the cynicism of human intercourse in the subsequent decade. In the early 1920s Expressionist chiaroscuro dominates, but later a brighter but harsh palette comes into play. The gaze is clear-eyed, often satirical. In the case of Harbour Drift, the influence of Soviet Constructivism is also evident: although the characters project powerlessness, the narrative is propelled by montage.

My examination of Harbour Drift still needs to engage the issue of its director Leo Mittler. I will take that up with my next entry.

_________________________________________________________________

(1.) Tragedy of the Street is directed by Bruno Rahn, a filmmaker no less obscure than Leo Mittler. Rahn died just 37 years of age the year Tragedy was released after directing eight features. Harbour Drift does indeed echo the earlier film; its heroine is an aging prostitute (played by Danish star Asta Nielsen) who invites a drunken middle-class youth to her room with unfortunate consequences. Unlike Harbour Drift, Tragedy of the Street obtained an American release in 1928 under the title Women Without Men. Said Mordaunt Hall in the New York Times, “As a bit of photography – in the continental manner – Women Without Men is interesting; as an entertainment it is not much to get excited about.” Perhaps this opinion was shared by those deciding whether Harbour Drift would export well. (return)

(2.) Kracauer too links Harbour Drift to Mother Krause’s Journey to Happiness in a section of his book devoted to films with “leftist inclinations” and the influence of Soviet film, but he is much more sympathetic to it than Eisner. Like Harbour Drift, Mother Krause failed to obtain an American release. The film is substantially discussed in the second part of Jan-Christopher Horak’s two-part essay on Prometheus. (return)

Comments