Listmania redux:

The Greatest Documentaries of All Time, part one

My friend Howard Curle emailed me a couple of weeks ago, mentioning a new Sight and Sound list with the rather bombastic title The Greatest Documentaries of All Time. He suggested that Cinematheque programmer Dave Barber, John Kozak (head of the University of Winnipeg film department) and I all put together our own documentary lists to discuss at a get-together coming up at the end of the month. And so on the bus to work, I started compiling a list in my head before looking at the Sight and Sound list on-line.

The timing of this seemed fortuitous as I’d been recently thinking about the whole phenomenon of list-making as something we seem to be driven to do. In this case, the subject of the list seems to require a lot of preliminary definition-making, starting with the question: What exactly is a documentary? Are the series of remarkable portraits of artists and composers made by Ken Russell at the BBC in the ’60s documentaries? They use actors, reenactments, and impressionistic visual techniques in an attempt to get inside the creative process. And what about Peter Watkins’ hybrid works from Culloden through Le Commune? He uses amateurs playing real historical figures, often foregrounding the technology of filmmaking as an element in creating meaning; but he also uses documentary techniques on speculative subjects extrapolating from present events into possible future consequences. And how can you isolate a single work by, say, Humphrey Jennings? Or Errol Morris? Just one by Albert and David Maylses? One by Werner Herzog?

Already, the project was shaping up as unwieldy, with too many possibilities (and requirements?) to reduce it to a manageable scale. Often, one’s first impulse is to be dutiful, to reel off the important titles, the ones of greatest historical significance – Vertov’s Man With a Movie Camera, Harry Watt and Basil Wright’s Night Mail, Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will, and so on, all hugely influential – but the titles that quickly came to mind sitting there on the bus were the ones which had had the most significant and lasting impact on me personally. So, not then “the greatest”, but rather “my favourites” …

So my list is neither definitive, nor entirely representative of my own objective judgments – rather, it’s what sprang to mind spontaneously without looking anything up, films which pushed their way to the surface of memory in immediate response to Howard’s prompting. And as often as not, what surfaced was a particular filmmaker rather than an individual film. And looking at my list now, I can see that most of these films share a focus on human experience, often expressed against received wisdom or enshrined social and historical opinion. And perhaps some of them could be forcefully refuted as documentary.

The initial part of my list, then, consists of filmmakers with multiple worthwhile films:

Michael Apted (& Paul Almond)

Initiated in 1964 by Canadian Paul Almond and continued for half a century (so far) by Michael Apted, the 7 Up series stands as one of the most remarkable and long-lasting film projects, following a group of English people from the age of seven up to (so far) fifty-six (matched only by The Children of Golzow by Winfried and Barbara Junge, a 43-hour, 46-year project documenting the lives of residents of a small East German town through the communist period and on into the reunification of Germany). Offering a portrait of a half-century of English social change, the series also has the power to provoke deep levels of introspection in its audience.

*

Joe Berlinger & Bruce Sinofsky

The television-based team of Berlinger and Sinofsky had a remarkable feature debut with Brother’s Keeper, a fascinating, disturbing and deeply empathetic portrait of the elderly Ward brothers, semi-literate farmers in New York state who were brought to public attention by a murder trial. The team’s best subsequent work, the Paradise Lost trilogy (1996-2011), has also focused on a murder case in which the power of the authorities is wielded against outsiders whose guilt is assumed because they fail to conform to an acceptable image of normality.

*

Kazuo Hara

I first came across this Japanese filmmaker through The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On (1987), an intense and uncomfortable account of Kenzo Okuzaki, an aging World War Two veteran who searches out officers of his old regiment to force them to admit to war crimes. Okuzaki is an unstable, even dangerous man, pulling Hara into situations which frequently seem about to become very nasty; Hara himself is implicated in these situations as he films people’s pain and discomfort. But the film eventually becomes a dissection of the impossibility of ascertaining historical truth and the dangers of willful forgetting. All of Hara’s films have this edge of danger about them, an aggressive confrontation with the complacency of Japanese society concealed behind layers of formal politeness. His first feature, Goodbye CP (1972), is one of the most intensely uncomfortable movies I’ve ever seen, and that’s both its strategy and its purpose. Following the activities of Yokota Hiroshi, a man whose body is twisted by cerebral palsy, Hara exposes the brutally insensitive attitudes of the Japanese towards “defective” individuals; as he keeps filming, we see Yokota’s increasing despair of ever being accepted as human and, in a way, Hara’s relentless camera becomes implicated as it threatens to exploit Yokota’s pain as spectacle. The sequence in which Yokota attempts to read aloud a poem about his condition on a city street – drawing the attention of the police with his “disturbance” of the public peace – is devastating. In his second feature, Extreme Private Eros: Love Song 1974, Hara turned his camera on his own life, filming his fraught relationship with ex-girlfriend Takeda Miyuki, a woman determined not to live by standard Japanese definitions of gender roles. Like all his work, this too is intensely uncomfortable to watch, placing the viewer in a voyeuristic position which forces some degree of reevaluation about what underlies our interest in other people’s lives.

*

Werner Herzog

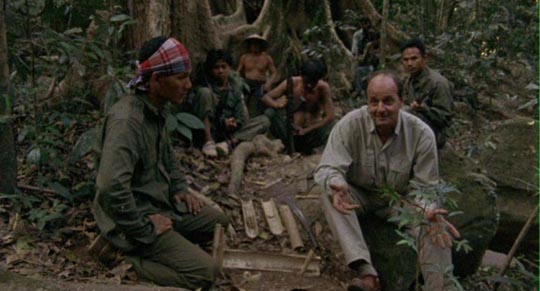

Werner Herzog, a key figure of the German New Wave, has had two parallel careers, with a great deal of overlap between them. His best features are often documentaries of his own obsessions and his compulsion to film almost impossible situations. His greatest drama, Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972), while ostensibly a story about a Spanish conquistador descending into madness as he journeys up a South American river, is a documentary of the mad relationship between Herzog and his star, Klaus Kinski. In Fitzcarraldo (1982), Herzog built an entire film around the complex and dangerous act of dragging a full-size steamship over a South American mountain. Alongside his dramas, Herzog has made a large number of documentaries which almost all focus on people involved in extreme situations; his work constantly plays with the border between sanity and madness, with how people seek out and deal with life-threatening danger. There’s Dieter Dengler, a German boy so impressed by the American planes which flew over his village at the end of WW2 that he grew up to be a pilot in the U.S. Air Force who was shot down over Vietnam, taken prisoner, and then escaped through the jungle. (Herzog inexplicably remade his documentary Little Dieter Needs to Fly [1997] as the inferior drama Rescue Dawn [2006].)

Most famously, Herzog turned the home movies of Timothy Treadwell into one of his most gripping examinations of obsession in Grizzly Man (2005), but perhaps more interestingly he has the ability to transform real situations into apocalyptic meditations on the strangeness of the world and the smallness of human beings within it: the burning oil fields of Kuwait in Lessons of Darkness (1992); the bizarre world beneath Arctic ice in the hybrid Wild Blue Yonder (2005), which also contains some of the most fascinating home movies made by NASA astronauts in their capsules; the visually stunning expanses of Antarctica and the surprisingly “ordinary” people who choose to live and work there in Encounters at the End of the World (2007); the exploration of Kaieteur Falls, Guyana, with an airship in The White Diamond (2004), a location as strange and impressive as anything in Avatar. Herzog is like a 19th Century explorer who has managed to harness 20th Century technology to give form to his obsessions.

*

Chris Marker

Are the works of the late French film and video artist Chris Marker documentaries? They’re more often described as film essays, and their overriding characteristic is their meditative quality. Marker starts from actual situations, but then delves down to seek underlying meanings in his own responses to those situations. The reclusive Marker made a mystery of his own life (claiming to have been born in Ulan Bator, Mongolia, though more likely it was Belleville in Paris or Neuilly-sur-Seine). Like many French intellectuals, he leaned towards the Left although his work is too nuanced to adhere to any party lines. In the ’60s and ’70s, he made and contributed to a substantial body of work critical of the political and social issues of the time – A Grin Without a Cat, Far From Vietnam, Le Joli Mai. He made a pair of documentaries about significant filmmakers: AK (1985), a portrait of Akira Kurosawa during the production of Ran, and The Last Bolshevik (1993), about the Soviet filmmaker Aleksandr Medvedkin. My first encounter with Marker was, not surprisingly, his brilliant science fiction short La Jetee (1962), but it was his superb essay on landscape, memory and the power of film, Sans Soleil (1983), which cemented my admiration for his work. Is this richly layered film a documentary? It certainly contains visual documentation of Japanese culture, Icelandic landscapes, and San Francisco, but these are just the jumping off points for a poetic meditation about how our experience of the world is rooted in, shaped and altered by the limitations of our perceptions and the vagaries of memory. Sans Soleil is an inexhaustible film, one which can be returned to again and again to prod our capacity to see and think about our own experience.

To be continued …

Comments