Listmania redux: The Greatest Documentaries of All Time, part two

While there’s a great deal to be said for what might be called investigative documentary (Charles Ferguson’s No End In Sight and Inside Job; Alex Gibney’s Taxi to the Dark Side; Jehane Noujaim’s Control Room) and informational film (I’m a big fan of the work which came out of the British Transport Film unit under Edgar Anstey, with its hundreds of industrial and tourist films produced between 1949 and the mid-’70s: the BFI has so far released about 48 hours of them on twelve 2-disk sets), but when I started to think about this list of favourites, I gravitated immediately towards works which focused on character and narrative – perhaps because the telling of stories is so ingrained in us and “true” stories so often have more depth and insight than even the best fiction.

The Maysles Brothers

There are few filmmakers with a finer sense of character than the Maysles brothers, Albert and David. Their work embodies an eclectic range of subjects: they book-ended the pop culture of the ’60s with a lively verite account of the Beatles’ first US tour in 1964 (an excellent companion for Richard Lester’s A Hard Day’s Night, which was released virtually simultaneously) and the bleak Gimme Shelter (1970), which seemed to put a decisive end to the decade’s exhilarating sense of freedom and possibility. Since the early ’70s, they’ve been documenting the environmental art projects of Christo and Jean-Claude in a series of fascinating films which together have evolved into a study of the intersection between art and social practice (each project centres around the social and political problems of transforming communal, public space for aesthetic as opposed to economic purposes), a project which Albert has continued since David’s death in 1987. But the brothers’ greatest films arise out of the intimate relationships they developed with people existing on the fringes of society.

Grey Gardens (1975) is probably their best-known film, a loose, affectionate portrait of Edith Bouvier Beale and her daughter Little Edie, relatives of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis who lived together in a decaying mansion in East Hampton. Although criticisms are still leveled at the film for supposedly exploiting the two women, the relationship between subjects and filmmakers is foregrounded throughout the film, developing into some kind of friendship, with the finished film actually giving Little Edie a kind of celebrity which transformed her from a seemingly dysfunctional outsider into a social and fashion phenomenon in New York on her own terms.

The initial discomfort a viewer feels at intruding on these women’s lives gradually gives way to something warmer and more positive as the Maysles brothers dig beneath the surface and allow us to see them as individuals, to get a sense of how their lives have come to this point, and ultimately to feel empathy and a genuine liking for them.

But my personal favourite among their films (perhaps because it was the first one I saw; perhaps because I’m more predisposed to respond to bleakness and despair) is Salesman (1968), a stark dissection of life on the fringes of society presented through the experiences of several door-to-door Bible salesmen, one of whom is failing. It’s a brilliant look at the emotional and psychological costs of work, where survival depends on investing meaningless activities with energy and conviction … and what happens when the ability to play that game is finally exhausted. Salesman is heartbreaking.

*

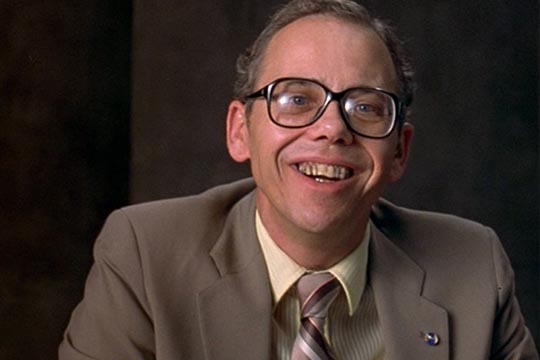

Errol Morris

Errol Morris has built a career out of his fascination with looking at other people. His gaze (aided by a machine of his own invention called the Interrotron which is designed specifically to violate the traditional imperative to “not look at the camera”: using a combination of mirrors and lenses, it permits Morris to have an intimate face-to-face conversation with his subjects while they gaze directly into the lens) is unflinching, though not always capable of digging below a hardened surface (I haven’t yet seen The Unknown Known, his feature-length interview with the insidious Donald Rumsfeld, but by all accounts the former Secretary of Defense has uncrackable self-righteous armour which makes it impossible to pry any kind of honest introspection out of him).

Morris, with his broad range of enthusiasms, seemingly has the ability to make just about anyone interesting on screen. In his first feature, Gates of Heaven (1978, made in part in response to a challenge by Werner Herzog), he turns a dispute over a run-down pet cemetery into a heart-breaking examination of character and the effects of failed ambition. In his third film, the one which brought him to prominence as a documentary filmmaker, he embarked on a rich, multifaceted investigation of the ways in which the criminal justice system is deformed by the actions of flawed people who are driven to create narratives which entangle other people’s lives and, in this case, send an innocent man to death row.

The Thin Blue Line (1988) recounts the case of an ordinary man, Randall Adams, who through a set of essentially random circumstances finds himself on trial for the killing of a Dallas police officer. The cast of characters includes Adams (on death row at the time of filming); David Harris, the probable killer, underage at the time and thus ineligible for the death penalty and so not a desirable suspect from the point of view of a police department and prosecutor’s office which wanted someone to die for the crime; various lawyers on both sides of the case; and a number of witnesses who suddenly found themselves minor celebrities when they stepped forward to testify. Morris was criticized by some for using “improper” techniques such as reconstructions of the event from various different angles – an approach which violated some sense of documentary purity. But the film is brilliantly constructed, those impressionistic montages used to force the viewer to reevaluate again and again what the interviewees are saying, problematizing the idea of pure, objective knowledge, and thus calling into question the principal underlying fiction on which the justice system rests: that there is an untainted knowable truth about human character and the actions which arise from it.

While The Thin Blue Line was ultimately instrumental in bringing about the release of Adams, Morris’ approach is far from muck-raking investigative journalism. His enquiries exist on a more philosophical plane, constantly searching for the limits of knowledge and certainty (as in the devastating case of Fred Leuchter in Mr Death [1999], in which a man driven by amateur interests sets out to “prove” that the Nazi gas chambers never existed, his results taken up by various Holocaust deniers like David Irving, despite the fact that there was no scientific validity to the crude tests Leuchter made on scraps surreptitiously taken from the ruins of Auschwitz); but the techniques he uses are equally powerful when used to explore the ways in which people create a sense of meaning out of existential uncertainty (as in his masterpiece Fast, Cheap & Out of Control [1997], about the ways in which we use work to instill a sense of value in our lives).

In contrast to the seemingly loose, observational style of the Maysles brothers, Morris uses often elaborate cinematic strategies to pursue his concerns – the increasingly complex intercutting among his four subjects in Fast, Cheap & Out of Control are an endlessly rich demonstration of the possibilities of using editing to create larger meanings which transcend those inherent in the specific material of the film. At his best, Morris pursues documentary as a form of art.

*

Marcel Ophuls

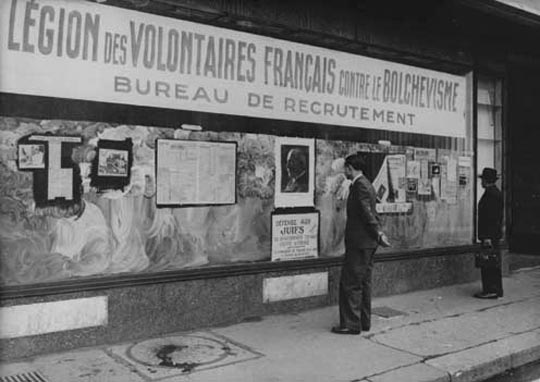

The son of famed French director Max Ophuls, Marcel Ophuls has also spent much of his career seeking elusive truths, but within a more political/historical context than Morris. Ophuls has frequently worked on an epic scale and many of his films revolve around moral issues arising from the Second World War and Naziism. To some degree, Ophuls seemed to need a certain historical distance to provide perspective (his 1972 film about Northern Ireland, A Sense of Loss, was unable to come to terms with an on-going situation which was so messy and complicated), while his examination of the idea of war crimes, The Memory of Justice (1976), wasn’t entirely successful in conflating the judicial concepts formulated through the Nuremberg trials with what the U.S. had been doing in Vietnam.

The first of Ophuls’ two greatest works is The Sorrow and the Pity (1969), an examination of France and the French people during the Occupation, which includes such a wide range of voices – ordinary people, politicians, collaborators and resistance – that the very idea of sustained moral behaviour in a world which had been turned upside down becomes impossible. By revealing the complexities of that historical period, Ophuls makes it increasingly difficult for the viewer to sit back and make easy moral judgments. As something of a companion piece, Hotel Terminus (1988) ultimately demands moral judgment. The story of Klaus Barbie, the sadistic head of the Gestapo in Lyons during the Occupation, comes to focus on what came after the war and the implications of Allied behaviour in actually aiding some of the worst Nazis to escape punishment (there was something of an underground railroad which spirited people like Barbie out of Europe, often to safety in South America), supposedly as part of the post-war shift towards anti-communism. While many of the witnesses in The Sorrow and the Pity made what in retrospect appear to be objectionable choices in response to oppressive, frequently life-threatening situations, the post-war behaviour of western politicians and intelligence operatives remains far more difficult to excuse; even given the ideological motivations, saving monsters like Barbie in the name of fighting a new enemy (who had formerly been an ally in the fight against Barbie and his ilk) seems unjustifiable on any level.

Ophuls at his best brings complex historical situations to life, throwing light on the ways in which people behave within social and political situations which offer no easy answers.

*

Hans-Jurgen Syberberg

While Ophuls uses traditional documentary techniques for his investigations of moral behaviour, Hans-Jurgen Syberberg’s work comprises a rich phantasmagorical meditation on the evolution of modern Germany. By conventional standards, it may be questionable to call Syberberg’s work documentary at all; although his films are built on a solid foundation of the historical record, he extrapolates from that record in imaginative ways, using dramatizations and a heightened, circus-like atmosphere to explore the formation and implications of the German national character (in itself a concept open to question).

Throughout the ’70s, Syberberg was involved in a massive project to – well, not explain, but rather explore how one of the most cultured societies in Europe could have culminated in the rise of Naziism, the quest for world domination, and the monstrous project of the Holocaust. The result was three unique films: Ludwig – Requiem for a Virgin King (1972), Karl May (1974) and Hitler – A Film from Germany (aka Our Hitler, 1977), which together run almost thirteen hours. Syberberg pulls in elements of high and low culture (and sometimes it’s not clear which is which – Wagner and his excesses are a major element in the trilogy), revealing a rich and complex mixture of philosophical thought and blatant kitsch which complicate the German pretension to intellectual superiority with the crass romanticism which all too often defined the culture’s sense of its own greatness. The trilogy puts on display the aggrandizing excesses of Ludwig II, King of Bavaria and builder of mid-19th Century fairytale castles, the romanticized fictions of Karl May, whose imagination colonized vast areas of the world with fantasies of noble savages and heroic adventurers, and finally Hitler himself, whose dream of empire was rooted in those same 19th Century romantic notions of German superiority (enacted to a soundtrack of Wagner’s rousing music).

These films constitute a monumental feat of imagination, all seemingly played out within the walls of a cluttered studio full of cultural bric-a-brac, with actors and puppets playing out historical events against rear-projected imagery of vast halls and landscapes. At the centre, Syberberg is the ringmaster viewing it all with a mixture of wry humour and perplexed disdain.

Made in the midst of the trilogy, but more conventional in form, is Winifred Wagner und die Geschichte des Hauses Wahnfried von 1914-1975 (1977), a riveting five-hour interview with the daughter-in-law of Richard Wagner who, from 1930 to 1945, managed the Bayreuth Festival which had been established in the 1870s by Wagner himself as a kind of official home for his repertoire. Born in England, Winifred was adopted by a distant relative in Germany after her parents died, and she met Hitler in the early ’20s. After he was jailed following his failed putsch, she apparently sent him aid parcels (he may have written Mein Kampf on paper she supplied). Even thirty years after the end of the war, Winifred remained loyal to Hitler, viewing him from the perspective of his admiration for Wagner rather than his actions as dictator and genocidal monster.

Syberberg has had a rather conflicted position in Germany, his views on history and culture frequently seen as tendentious and even offensive.[1] This is perhaps not an unreasonable response to his work, but it’s undeniable that his films provoke deep consideration of important questions about the relationships between culture, art, politics and the flow of history.

*

Agnes Varda

It would be difficult to get farther away from Syberberg than Agnes Varda. One of the progenitors of the French New Wave (although generally set somewhat outside of that rather testosterone-driven movement which was prone to deny the roots out of which it grew in an effort to claim its radical originality), Varda has focused intensely on personal experience in her films, with social and political concerns viewed through the effects they have on individual lives (Cleo from 5 to 7 [1962], Vagabond [1985]). She has worked in documentary alongside drama right from the beginnings of her career, often taking very personal subjects. Following several films in the ’90s devoted to her late husband, filmmaker Jacques Demy, Varda took herself as subject in a pair of documentaries which are so full of curiosity and wonder that they seem capable of transforming the most hardened cynic into a believer in the endless pleasures to be gleaned from life.

The Gleaners & I (2000) is a deeply affectionate study of people who find worth in things discarded. These people who pick through the detritus of a wasteful materialistic society come to stand in for Varda herself who has spent a lifetime collecting experiences and recording the details of what she has seen. One of the warmest and deepest characteristics of this charming, funny and ultimately moving film is Varda’s fascination with her own aging and what it means to be nearing the end of a very full life. Shooting the film herself on a small video camera, she continually takes moments to observe herself, the shape and textures of her own hand, her own face bearing signs of age (she was in her early 70s when she made the film). The Gleaners & I is imbued with a sense of wonder about the simple fact of being alive.

In The Beaches of Agnes (2008), now 80, Varda looks back over her life and career with that same sense of wonder, almost surprised at what she has seen and done. Beaches is more loosely structured than Gleaners, a relaxed collection of reminiscences mixing humour and nostalgia, perhaps an occasional touch of sadness (a large part of the film is devoted to her life with Demy), but her pleasure in remembering – and the visually inventive ways she finds to express those memories – has an infectious charm. These late works by one of France’s finest directors forcefully counter the grim view of aging our society is prone to hold; spirited and charming, they confirm that age is merely a state of mind.[2]

To be continued …

_________________________________________________________________

(1.) After seeing Hitler – A Film from Germany in an all-day screening at the 1981 Hong Kong International Film Festival, I visited the local offices of the Goethe Institute to ask whether the script had been published in English as there was really too much to take in at a single viewing and I wanted to spend some time mulling over the film. I got a frosty reception and was told that “in Germany we don’t really like Syberberg.” (return)

(2.) When I was in Paris working on Faces in the Crowd in 2010, a friend from Winnipeg was planning to visit me for a couple of weeks. She’s a huge fan of Agnes Varda and was eager to get a chance to visit the filmmaker. Having contacted Varda by email, she learned that the director was going to be leaving Paris the same day my friend was arriving. The question was whether there would be an opportunity to connect. So my friend insisted that I call Varda’s company, Cine Tamaris, to see if anything could be arranged. I found the number on-line and phoned. The person who answered spoke accented English and listened to what I had to say, though she seemed a bit impatient, even irritable. It looked as if a meeting would be impossible. Then, just minutes after the call ended, the phone rang and the same woman asked for more details about my friend’s arrival time and it finally dawned on me that I was actually speaking to Agnes Varda herself. The timing didn’t work out, but it was touching that she was doing her best to find a way to accommodate this fan from Canada.

Comments

One thought on “Listmania redux: The Greatest Documentaries of All Time, part two”