Robots “R” Us

Watching several movies recently which feature killer robots, I can’t help wondering why we human beings are so obsessed with creating replicas of ourselves which tend to turn against us, or perhaps more disturbingly turn out to be so identical to us that you can’t tell the difference. In the latter case, it often turns out that the story’s protagonist doesn’t even know that he or she is not in fact human (Deckard and Rachael in Blade Runner, Captain Cragis in The Creation of the Humanoids, Sam Bell in Moon – the latter, of course, a clone, which is thematically very similar to robots and artificial intelligence in terms of uncertainty about human identity). “Playing God” has been a theme probably since we as a species invented religion; perhaps it’s rooted in resentment of the idea that we are merely the imperfect results of a superior being’s intentions. If we could match our gods’ performance, we wouldn’t feel so inconsequential – and just maybe we could do a better job. And yet, in these fantasies of godhood, the results of our work often turn out to be disastrous – our creations are either destructive monsters or they turn out to be our superiors, relegating us yet again to the subservience we were striving to break out of.

The flaws in this endeavour are apparent even in the classic pre-technological versions of this story. The Golem, created (like Adam) from clay and animated by magic, is a lumbering speechless thing which like as not becomes a danger to the community it was created to protect. In the first sophisticated literary version, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the creature built from spare body parts repels people with his hideous appearance despite the fact that inside he’s a cultured, self-aware, introspective being. It’s Frankenstein’s inability to take responsibility for his act of creation which results in disaster; the model for the creature was Milton’s Lucifer, rejected by God and responding with ego-centred rebellion.

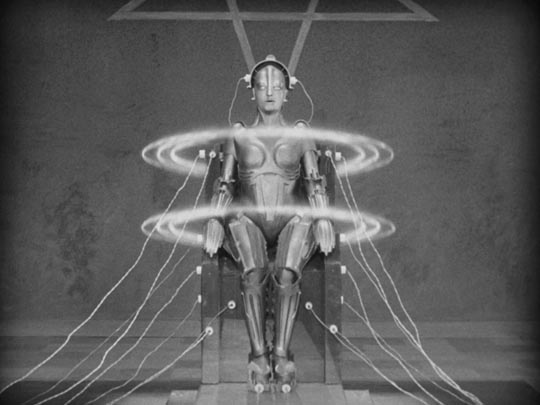

Frankenstein’s creature and the Golem both made early appearances in the movies, but it was Fritz Lang who introduced the technological version of man-made man (or woman) in 1927 with the robot-Maria in Metropolis. Many of the themes associated with robots had their origins here: the confusion between human and machine, the misguided or even malevolent intentions of the robot’s creator, the undermining of social stability by confusion about the borders between the human and non-human. And also the use of technology to unleash what we strive to repress: the robot created by Rotwang is modelled on the chaste, maternal figure of Maria, the moral conscience of the oppressed working class. But the machine-woman is imbued with an unbridled sexuality which, given Maria’s moral authority, inspires the workers to let loose their ids, coming very close to destroying themselves and the city they serve.

It’s interesting to note that while in the real world robots to date have been designed to meet the practical needs of manufacturing or to carry out functions it’s too impractical or dangerous for people to perform – that is, their design derives from their function as machines rather than from some desire to emulate the human form – in popular culture, their primary purpose has been to reflect human form and behaviour. In fact, even when the machine lacks anthropomorphic physical attributes, it tends to be imbued with human personality and motivations: HAL in 2001: A Space Odyssey, Colossus in The Forbin Project, Proteus in Demon Seed. But what’s particularly interesting in these cases, where the focus is on human types of thought and feeling, is that these machines assume a pathological character; they express their deepest humanity in acts of violence rooted in their own sense of superiority. To be human, they imply, is to be sociopathic at best, or more likely psychopathic. We imbue what we create with our own darker natures and find ourselves at the mercy of our technological children.

The essence of this myth about ourselves and what we create is the fear that we are innately destructive, that every step we take towards “progress” threatens our own existence and that somehow it’s beyond our power to stop ourselves going down this path. These stories are about our own helplessness against ourselves. They are, in fact, a recognition that we are constantly threatening to replace ourselves through our capacity to develop new technologies. And we are strangely ambivalent about this.

The term Luddite has long had contemptuous connotations in popular opinion, and yet the artisans of the early 19th Century who fought against the new machines which were transforming the British textile industry acted out of a very rational awareness that the rising capitalist class was seeking to enrich itself by displacing the traditional working class; these supposed enemies of progress were engaging in a perfectly reasonable fight for their own survival. Our technological history is a long, often destructive narrative of human beings seeking ways to replace themselves with machines – in the earlier stages on a purely mechanical level, but more recently on the level of intelligence and even personality with the quest for artificial intelligence. We are cursed with a strange certainty that we can create something better than ourselves which can supersede us as the dominant “lifeform” on our planet, and for some this appears to be a desirable thing.

Hence the often reiterated dual themes of loss of self, of identity, and simultaneous empathy for the machine which run through movies featuring robots.

*

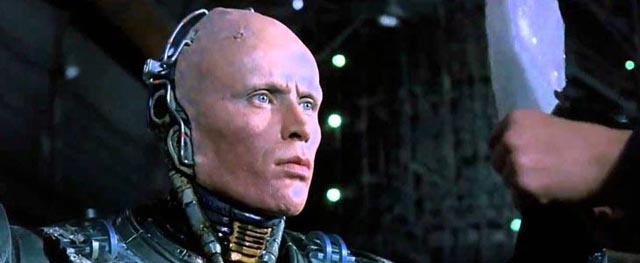

RoboCop (1987)

While there are classic robots which are purely machine (Robbie in Forbidden Planet, Gort in The Day the Earth Stood Still, Arnold in The Terminator), it seems more common for movies to mix an element of the human into the technology. This can range all the way from Harry Benson in The Terminal Man (1974), adapted by Mike Hodges from Michael Crichton’s novel about a man who has a chip implanted into his brain which is designed to prevent seizures but instead turns him psychotic, to RoboCop (1987), in which the few remaining fragments of Officer Murphy’s brain after a brutal killing are implanted into a humanoid machine. In the former case, the chip is designed to control the brain; in the latter, the brain is merely a component involved in controlling the machine. In Terminal Man, Harry loses his sense of humanity to the machine, while Murphy in RoboCop reasserts his humanity through the machine.

Paul Verhoeven’s movie is a violent satire on the assault against society by virulent capitalist corporations and the tendency of a technocratic political system to transform inexorably into a police state. Watching it again today, it’s rather chilling to realize that the satire is probably more pertinent now than it was even during the Reagan era.

Having been literally shot to pieces, Murphy is declared dead and what scraps remain become the property of the ironically named Omni Consumer Products (the corporation doesn’t seem to sell things to people so much as sell to the authorities products designed to control the population). Human beings are mere resources in the quest for corporate profits and company rights supersede human rights (a philosophy apparently now endorsed by the U.S. Supreme Court). As Murphy gradually reawakens in his metal body, his humanity returning in the form of surfacing memories of his previous life, irritated executives demand that his controllers simply erase his cortex because his reemerging consciousness is interfering with the function of their product, and thus jeopardizing profits.

While RoboCop ends on a seemingly positive note, with Murphy fully restored inside the robot body, his humanity isn’t enough to overthrow a system so deeply entrenched and in the first of the two lesser sequels (1990, directed by Irvin Kershner), he finds himself fighting a holding action against the corporation which is still expanding its control over the city. In the third film (1993, directed by Fred Dekker), the satire has been replaced by a kid-friendly fable in which ordinary folks stand up and, with Robo’s help, unconvincingly bring down the corporation. By this time, Verhoeven’s visceral comic book has been reduced to Saturday morning cartoon. But nonetheless, the RoboCop character stands as an exemplar of the effort it takes to assert humanity against the encroachments of technology in the hands of pathologically greedy corporate capitalism.

*

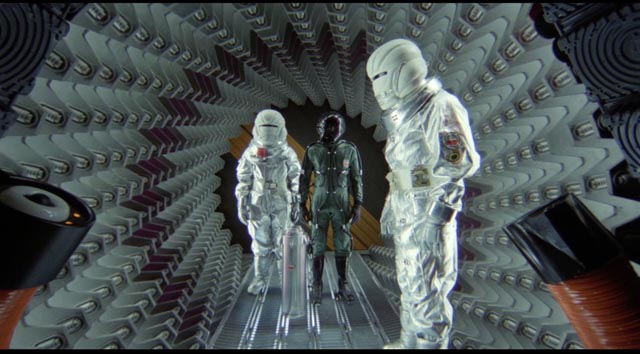

Saturn 3 (1980)

No such heady theme surfaces in Saturn 3 (1980). Conceived by production designer John Barry (Star Wars, Superman) as a low budget sci-fi outing, it was eventually taken out of his hands and directed by producer Stanley Donen. Now Donen was a considerable director of musicals, comedies and a couple of lightweight thrillers which emulated Hitchcock, but this was his sole attempt at science fiction and action, and the results are odd to say the least. Visually there are moments which would seem more appropriate to a Hollywood musical (particularly the non-sensically choreographed launch bay sequence in which a group of space-suited figures form into a chorus line as Benson [Harvey Keitel] walks to his shuttle), while narratively (script by novelist Martin Amis based on Barry’s idea) little makes sense in that way common to sci-fi made by people unfamiliar with the genre – all you need is spaceships and robots and who cares about story logic and character motivations?

Essentially a sexual triangle played out on large, elaborate sets which would have done a ’60s Italian space opera proud, Saturn 3 gives us a rather creepy relationship between 64-year-old Kirk Douglas and 33-year-old Farrah Fawcett. Perhaps it’s just that the intervening years have made us more aware of Hollywood’s skewed age standards, but the sight of this pair engaged in nude sex scenes is more disturbing than the movie’s deliberately horrific effects. Adam and Alex – he’s a research scientist working on new plant technology to help feed Earth’s starving population; she’s his assistant and designated sex toy (a long-standing tradition in pulp sci-fi has it that women exist primarily to serve male pleasure; this is almost satirized in the moment when Benson tells Alex that he would like to use her body) – have been enjoying themselves for years on one of Saturn’s moons and apparently putting in more time in bed than in the lab. Benson is sent to speed up production. At least, that seems to be the situation – except we’ve already seen Benson kill the officer who was supposed to come to the base, taking his place. We have no idea what his actual motivation is – or in fact who he really is.

Benson has brought along a robot (called Hector, one of those pointlessly obscure classical references that people like to insert into sci-fi stories) which is supposed to help speed things up, although again the machine’s intended function is never made clear. Benson programs Hector through a direct link with his own brain and so the robot takes on its master’s own psychotic tendencies, including his sexual obsession with Alex. Things from there devolve to standard running-for-your-life-through-corridors-and-air-ducts action and by the time the movie reaches its climax Hector has killed Benson and stuck his severed head on its own neck, speaking now with the crazy guy’s voice.

That head business points to just one aspect of the conceptual problems with the movie: why did Hector’s designers give him a massive humanoid body, but neglect to include anything resembling a head? Merely so he could “complete” himself by appropriating Benson’s head? And why do space pilots in this particular future all fly horizontally through Saturn’s rings, risking countless collisions with the debris, rather than skirt around them altogether for the sake of safety? This last doesn’t even offer impressive visuals to compensate for the stupidity as, like most of the film’s effects, it’s pretty much on a par with Dr Who.

Although the silliness of Saturn 3, with its kitschy design and nonsense action, has produced a small cult following (the Blu-ray has a commentary by Greg Moss who has created a website devoted to the movie), nothing makes much sense and the killer-robot is simply a perfunctory given. It doesn’t help while watching it that Donen decided to dub Harvey Keitel’s distinctive voice with a nondescript mid-Atlantic replacement courtesy of British character actor Roy Dotrice (it can’t have been because Keitel sounded “too American” as both the other actors are distinctly American; the commentary suggests that it was because Keitel had somehow annoyed Donen, which if true would really call the producer-director’s creative judgment into question). The extras on the Shout! Factory dual-format release detail much of the movie’s troubled history, but it remains somewhat unclear why Saturn 3 ended up the way it did. As a science fiction movie, it’s ridiculous; however, as a colourful, full-tilt, big-budget car crash helmed by a prominent Oscar-winning filmmaker, it’s quite fascinating.

*

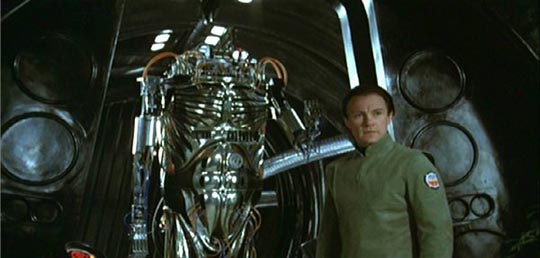

The Machine (2013)

Although produced on a much smaller scale, Caradog W. Jones’ The Machine (2013) is a more satisfying film altogether, made by someone who obviously understands and appreciates the genre. There’s nothing radically original about the story, but it’s well-written, visually inventive, with characters who behave in comprehensible ways and gain audience sympathy. Vincent (Toby Stephens) is a scientist working on AI in the near future, when the West is at war with China and seeking new weapons to carry on the fight. One line of research involves taking battle-damaged soldiers and enhancing their brains with chips to turn them into more efficient (less human) fighters (an obvious nod to Universal Soldier). The film begins with a test which goes wrong as one subject malfunctions and turns on the research team.

Vincent brings in applicants to help with his research and settles on the brilliant young Ava (Caity Lotz), who offers a fruitful new line of inquiry. What Vincent’s political and military masters don’t realize is that he is actually using their resources in an attempt to find a technological solution for his own daughter’s degenerative neurological disorder (something like Will Rodman trying to come up with a cure for his father’s Alzheimer’s in Rise of the Planet of the Apes). When it looks like there’s no hope of saving his daughter’s life, Vincent uploads her mind to his AI equipment; perhaps he can install her into a robotic body and keep her alive that way.

When Ava is killed by a Chinese assassin, Vincent creates a new prototype robot into which he puts her consciousness. Essentially a newborn child, we see robot-Ava growing aware and taking delight in her existence (the film’s most visually poetic sequences); but unknown to Vincent, his boss Thomson (Denis Lawson) pushes ahead to turn the machine into a killer, something which creates internal conflicts with the remnants of Ava’s personality. Along with the damaged earlier subjects of these experiments, a group of modified soldiers who, unknown to their masters, have developed a mutual telepathic group mind, robot-Ava embarks on a rebellion.

In The Machine, it’s the military masters who are inhuman, while robot-Ava develops a superior moral sense which refuses to participate in the war.

The Machine is aided greatly by fine performances from Lotz as the robot and Pooneh Hajimohammadi as Suri, the leader of the telepathic soldiers. It also has something like an upbeat ending, which makes it seem oddly refreshing despite the violence inherent in the story. Whereas in an obvious precursor like Eugène Lourié’s The Colossus of New York (1958), in which a doctor tries to preserve his brilliant son’s intellect by placing his brain inside a robot with predictably disastrous results (separated from his natural body and human senses, the son goes mad and sets out to destroy humanity), robot-Ava attacks those who would abuse and dehumanize the people under their power and regains her humanity by fighting for justice. With its spare but intelligent script and judicious use of CGI, The Machine is one of the best recent science fiction movies.

Comments

Wouldn’t it be refreshing to see a sincere ‘robot’ production celebrating how good life is. But I guess that’s too radical.

Ah, but where would the drama be in that? Would anyone be interested in Hamlet if everyone in the family got along?