Criterion Blu-ray review: Vengeance is Mine (1979)

A convoy of police vehicles winds its way along a curving mountain road at dusk. Inside one of the cars, a man sits between two detectives, seemingly calm and in good humour. He is Enokizu Iwao and he has just been arrested following a series of murders and other crimes throughout Japan in the Fall and Winter of 1963. He seems to have no conscience about his crimes and feels no need to explain himself; in fact, he sees no point in saying anything about these crimes as the police know he’s guilty – why bother to make a confession? From the small interrogation room to which he’s been taken, we flash back to the first brutally graphic killings and gradually, in ever widening ripples, through Enokizu’s whole life. But really there’s no clear explanation of his motives and his life becomes the representation of a sickness in the national soul.

On first viewing, Imamura Shohei’s Vengeance Is Mine (1979) can seem a bewildering experience. The film, with its chilly detachment, disturbing violence and charged eroticism, refuses to play by standard narrative rules, frustrating expectations about where it is heading and what it might mean. But it gains in clarity the more the viewer knows about its director and the rest of his work.

Imamura Shohei is at once one of the most interesting yet least well-known Japanese filmmakers of the post-World War Two era. Having grown up during the height of Japan’s Imperial rise through the ’30s, subsequent fall after the war, and rise again with the remarkable economic recovery following defeat, Imamura had an ingrained distrust of authority and the cultural forces which supported it. The son of a doctor, his interest in theatre – and later film – sidetracked his university education, and as a young man after the war, he made a living trading in the black market which was rampant during the American occupation. It was in those years that he came to know and become fascinated with members of the underclass – petty criminals, prostitutes and such. The struggle to survive on the margins and his hatred of authoritarianism combined with an interest in existentialism to form the basis of his subsequent work: an on-going study of individuals and personal identity within and against the constraints of society.

Imamura’s interest in film apparently began with a viewing of Kurosawa Akira’s Drunken Angel (1948) with its portrait of a petty gangster much like the people Imamura knew from his own black market days. After leaving university, Imamura attempted to become an assistant to Kurosawa, but the rigid structure of Toho Studios made it impossible for him to get in. Instead, he took an exam and got a job at Shochiku, where he was assigned to Ozu Yasujiro’s crew. He was temperamentally unsuited to Ozu’s style of filmmaking, but nonetheless learned a great deal about craft through the three years he worked for the great director.

But once again, the rigidity of studio structure meant that Imamura would have had to wait years for a chance to direct. And so, when he got an offer from Nikkatsu, which had recently started operating again, he accepted. As is well-known now (thanks in large part to some excellent previous releases from Criterion, particularly two Eclipse sets: The Warped World of Koreyoshi Kurahara and Nikkatsu Noir), Nikkatsu was quite different from the more traditional studios, with a “younger” and more energetic attitude and a roster of productions driven by a modern as opposed to classical sensibility. The studio’s young directors were iconoclastic, their films jazz-driven and often anti-establishment, the Japanese equivalent of a mixture of Hollywood B-movies and ’50s youth films. Having written a number of scripts for other directors, Imamura was quite quickly given his own first film to direct, which became Stolen Desire (1958), the story of a university drop-out who joins an impoverished itinerant theatre troupe.

It was three years later, with his fifth feature, that he really made his first mark with Pigs and Battleships (1961), a film deeply rooted in his own black market experiences, about gangsters exploiting the opportunities afforded by a nearby U.S. naval base. This high-energy film is laced with satirical touches and detailed observation of a very specific social, economic and cultural milieu. After a series of similarly intense dramas focusing on the underclass, for a decade from the late ’60s to 1979, Imamura not surprisingly concentrated exclusively on documentary (partly because of some bad experiences with actors, but more importantly because he felt that fiction couldn’t get at the truths he was seeking to explore). But in time he realized that documentary too was constraining him and he moved back into fiction film, but often with a documentarian’s eye and choice of subject.

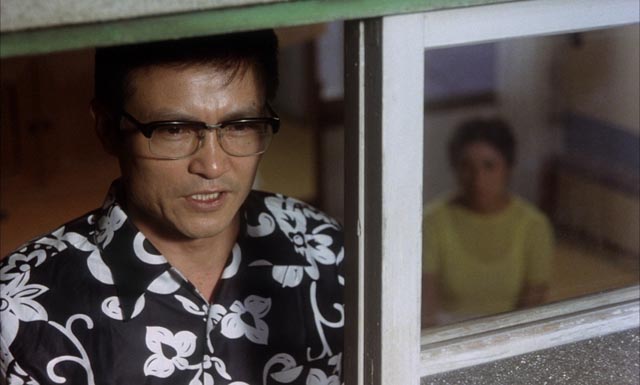

Imamura’s concern with the material circumstances of his characters’ lives continues throughout his work, along with a deep interest in female characters. In fact, it could be said that Imamura’s work forms a bridge between the classical social observation of Naruse Mikio and Mizoguchi Kenji (particularly in his frequent focus on female characters) and the later transgressive cinema of directors like Miike Takashi and Sion Sono, although perhaps the closest parallel would be with the savage politically-inflected gangster films of Fukasaku Kinji, particularly his epic five-part Battles Without Honour and Humanity (1973-74). And perhaps the keystone of that bridge is Vengeance Is Mine, with its cool, almost detached treatment of real-life serial killer Enokizu Iwao (Ogata Ken) and the people he encounters during his two-and-a-half month crime spree in late 1963.

Enokizu was born into an outsider community, son of a Catholic family in a society which held this difference in contempt. In a crucial flashback, we see his father (Mikuni Rentaro) publicly humiliated by a naval officer, the resulting sense of shame instilling not only a deep anger at authority but also a lasting contempt for his father. These fractured family ties, combined with being a social outsider, lead Enokizu into a life of petty crime during the American occupation and he spends some years in prison. On his release, his parents try to arrange a marriage, but he chooses another woman, Kazuko (Baisho Mitsuko), with whom he has two children. But normality seems to be impossible, and Imamura relentlessly dissects endless layers of corruption and hypocrisy which run through both the family and the larger society surrounding it.

Enokizu’s mother (Miyako Chocho) is sick and an intensely erotic attraction develops between his wife and his father; while Iwao is in prison, his father “takes pity” on Kazuko and arranges to make her sexually available to another man. At first she resists, but learning that this is sanctioned by the older man whom she desires, she submits while fantasizing that it is Enokizu’s father making love to her. In the film’s world, female desire, always constrained by financial limitations, traps women and makes them vulnerable to predatory men.

While on the run, Enokizu hides out at a small inn, pretending to be a university professor – a role which gains him instant respect from the woman who runs the inn, Haru (Ogawa Mayumi), and her mother Hisano (Kiyokawa Nijiko). Haru is in debt to a man who holds the mortgage on the inn, and he in turn for some reason pays the mother to spy on the sexual activity of the guests and the prostitutes who are called in to serve them. Haru becomes infatuated with Enokizu, even as he has a different prostitute every night. The mix of sexual corruption and financial insecurity makes these women easy prey for the egotistical, role-playing Enokizu, to the point where even when they learn that he’s not a professor but rather a killer on the run, they protect him – finally at great personal cost.

Vengeance Is Mine paints a grim portrait of a society with no moral bearings, where greed and insecurity govern virtually everyone’s behaviour, a thick stew of corruption out of which the senseless killer Enokizu bubbles to the surface. While a psychologically comprehensible motivation gradually emerges (as Tony Rayns points out in his commentary), with Enokizu driven by an Oedipal hatred of his father, and perhaps committing his brutal and senseless crimes in an attempt to smash that father’s religious beliefs, the film’s greater concern seems to be in exposing the nihilism and hypocrisy of the society which has shaped Iwao. All of his actions, from theft to fraud to murder, revolve around monetary gain, the use and abuse of other people just to get his hands on fairly paltry sums of money. Imamura is ultimately concerned with a sociological, even anthropological understanding of this character and his crimes, rather than an individualistic psychological explanation.

The disk

Criterion’s 2K transfer from a low-contrast print made from the original camera negative affords a richer image than their previous DVD edition. This is a dark film, shot in a restrained style – even the brutal murders near the beginning are treated with a kind of detached curiosity, displaying just how messy and difficult it is to kill – and the subdued use of colour is crucial to maintaining the story’s murky moral tone. The mono soundtrack is clean and clear at all times, and the disk has removable English subtitles.

The supplements

While not as rich in supplements as some of Criterion’s recent releases, the new Blu-ray repeats a brief conversation (10:17) between Imamura, Takeshigi Kunio and Benitani Ken’ichi in which he discusses his approach to the fact-based story of Enokizu, and adds an informative commentary by critic Tony Rayns, previously included on the Masters of Cinema edition of the film. There are also two three-minute trailers.

The accompanying booklet contains a couple of brief statements by Imamura, one on this film specifically, the other on his philosophy of filmmaking, as well as an essay on the film by critic Michael Atkinson and an illuminating interview with Imamura conducted by fellow filmmaker Nakata Toichi.

Comments