When “bad” can be good …

The concept of “bad movies” is more problematic than it may first appear. Amazon and IMDb are full of user comments to the effect that “this is the worst movie I’ve ever seen”, often attached to acknowledged classics, cult favourites and, indeed, indisputable works of cinematic art. (Often the justification for these dismissals is something on the order of “it’s not my kind of movie and I didn’t like it”, which in the commenters’ view makes the film in question – whether an old black-and-white drama in which people talk too much or a Tarantino epic in which there’s so much swearing and violence – “bad”.) The Medved brothers, Michael and Harry, first gained notice with a book called The Fifty Worst Films of All Time (1978), which included such titles as Alain Resnais’ masterpiece Last Year At Marienbad, but nothing by Ed Wood, who in their follow-up, The Golden Turkey Awards (1980), was dubbed the worst director ever. Which just goes to show that opinions about “good” and “bad” are generally not objective, but rather a matter of contingency (Wood was brought to the Medveds’ attention by readers responding to their first book), personal taste, and the nature of one’s own experience and understanding of movie history. Paradoxically, the Medveds’ smug put-down of Wood helped to raise the filmmaker’s profile to the point where he became one of the best known “bad” directors in the history of the medium, giving his cheap movies far more success than they’d ever known during his lifetime.

Personally, I feel that calling Ed Wood “the worst director of all time” is ridiculous. Surely the movies of the worst director would be unwatchable; and yet Wood’s work is endlessly entertaining and at times quite fascinating. Yes, by generally held standards of technique, he was clumsy, but there’s an odd quality to some of his films which approaches a kind of absurdist poetry. I prefer to think of him as the cinematic equivalent of a naive painter, one with no formal training and perhaps no understanding of the rules, but who nonetheless finds a way to express creatively something he needs to communicate. This is why, despite the greater popularity of Plan 9 From Outer Space (1959), Wood’s best movie is his first, Glen or Glenda (1953), which for all its absurdities and often mind-boggling use of seemingly random stock footage, is an intensely personal work by a filmmaker who put his own conflicted sexuality on screen when his predilections were far from socially acceptable. The result is an accidental surrealist masterpiece. (Here I’ll court ridicule by saying that I’d rather re-watch Glen or Glenda than sit through Bunuel’s Un Chien Andalou one more time.)

All of which is to say that any movie which garners enough attention to trigger that “worst” label is bound to contain something of interest. By most standards, Wesley Barry’s Creation of the Humanoids (1962) is a poorly made film, with almost non-existent sets and wooden acting; yet its (very talky) script by Jay Simms is an intelligent piece of science fiction writing about artificial intelligence and what it means to be human (thematically somewhat similar to Blade Runner). Yes, it would probably have been better printed as a story in a magazine than laboriously put up on screen by a man whose brief list of directing credits consists mostly of cheap westerns, but a science fiction fan can find the material absorbing despite the pedestrian execution. (It was reputedly a favourite of Andy Warhol, and even got a mention in Susan Sontag’s 1965 essay “The Imagination of Disaster.”)

In his notes for Grindhouse Releasing’s special edition Blu-ray of Amos Sefer’s An American Hippie In Israel (1972), John Skipp asks “What’s the difference between a malformed gem and a total piece of shit? For me, it’s sincerity.” And there’s certainly some truth in that, as can be seen by how painful so many deliberate attempts at producing a “cult movie” are. As viewers, we need to believe that the filmmaker was committed to what he or she was creating in order for us to derive genuine pleasure from it; if the director is in on the joke, our response tends to get short-circuited. (One of the very few exceptions I know of to this rule is Chris Windsor’s note-perfect sci-fi/horror/musical-comedy Big Meat Eater [1982], which works in large part because of its genuinely catchy musical numbers.)

This raises the possibility of cruelty on the part of the audience, the kind of snotty superiority expressed by the Medveds in their contempt for Wood. It’s a tricky thing, no question. And for a really sincere bad filmmaker, the laughter of an audience can be devastating. There was a legendary case at the Winnipeg Film Group back in the ’80s when a member made a half-hour movie called Blown Ice which attempted to plant a hard-boiled blaxploitation story about stolen diamonds and the price of crime in the not-so-mean streets of Winnipeg. Everything about the film misfired – the ham-handed dialogue, the overwrought amateur performances, the editing which shows no awareness of pace and structure – and at the premiere, the audience laughed. But the director had been completely earnest and he never made another film. There have been other less extreme cases, and often the general opinion is that if only the filmmaker had been able to embrace the response and accept that the results of his work were comedy and not drama, that is if the filmmaker could have been in on the joke, all would have been well. But of course that’s not how it works – the film is as funny as it is because of the deep sincerity which went into it; for the filmmaker to turn around and accept the comedic outcome would have meant a betrayal of self.

Personally, I feel that an acknowledgment of the filmmaker’s sincerity is essential to enjoying a bad movie. Merely laughing at it because one feels superior leaves a sour taste (which is why I’ve always disliked Mystery Science Theater 3000).

The really crucial difference for me between a merely bad movie and an entertainingly “bad” movie is that the latter has the capacity to surprise the viewer, that the shortcomings of the filmmaker result in the unexpected, catching you off guard. A merely bad movie so often slavishly follows tired and familiar forms, failing to raise anything you haven’t seen before. Wood’s supposed incompetence often presents us with something entirely unexpected – in Glen or Glenda, not merely the plea for understanding for transvestites and transsexuals, but those mind-boggling interludes with Bela Lugosi and stock footage of lightning and stampeding buffalo herds; in Bride of the Monster, not only the hilarious rubber octopus, but Lugosi’s impassioned speech about being outcast. That is, like good films, “bad” films have the capacity to engage the viewer on more than one level, to expand the way we see the medium.

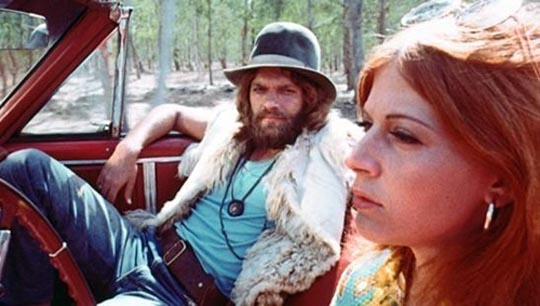

This is the case with Amos Sefer’s An American Hippie in Israel, the one and only movie made by this Israeli writer-director. Mike (Asher Tzarfati) is a Vietnam vet who walked away from the war looking for some place where he can live in peace and deal with the effects of being turned into a killer by his government. Landing in Israel, he meets various people, gets involved with a group of “hippies” for a bit of a love-in with folk songs … but everywhere he goes, he’s pursued by a pair of killer mimes in a big black car, essentially bringing death with him. With actress Lily (Lily Avidan) and another couple (Shmuel Wolf and Tzila Karney), Mike heads for a small barren island off the coast, where the group plan to establish a peaceful republic; not surprisingly given that there appears to be nothing to eat or drink on the rock, they quickly start to bicker and their dream collapses … because man, you know, is inherently destructive.

The film’s symbolism is obvious, as is the filmmaker’s sincerity, his desire to make a statement about the world in the wake of Vietnam and the failures of the counterculture. But Sefer’s untrained skills aren’t up to the task and An American Hippie in Israel is full of incongruities, painfully on-the-nose dialogue and technical deficiencies. Yet it also has those unexpected moments which keep the audience alert. These climax in a lengthy discussion on the island between Mike and the other man about their problems, in which the other man speaks Hebrew while Mike repeatedly insists “I can’t understand a word you’re saying – I don’t get you, man!”, a perfect illustration of the obstacles to mutual understanding which constantly plunge us back into conflict as well as one of the movie’s funniest scenes.

None of this implies that I watch “bad” movies with straight-faced seriousness. Filmmaker ineptitude can often produce a great deal of (inadvertent) humour, but the laughter doesn’t need to be condescending; in fact, it can be tempered by genuine empathy for the filmmaker’s failures (perhaps you need to have made films yourself to appreciate this, to recognize how easily one’s accomplishment can fall short of one’s ambitions). In fact, viewer pleasure can be greater when there’s a degree of empathy for the filmmaker; that feeling leaves you more open to appreciating whatever surprises might arise from a violation of accepted rules of movie-making – like the baffling mimes-of-death in An American Hippie in Israel, a metaphor for human violence as blatant and ill-conceived as Ed Wood’s warnings about nuclear destruction in Plan 9.

If you place movies along a spectrum from great to terrible, it’s the ones in the middle – the mediocre, the predictable, the formulaic – which are boring. Those at either end of the scale, the good and the bad, are the ones which offer surprises and insights and, perhaps, new ways of seeing the world. What counts most is that a movie engages the viewer in an active relationship with the filmmaker’s intentions … and sometimes a “bad” movie can do that as effectively as a masterpiece.

*

Ed Wood Addendum

On a trip to visit friends in Toronto in 1982 I had the opportunity to attend the world premiere of Ed Wood’s “lost” movie, Revenge of the Dead (aka Night of the Ghouls) at the Bloor Cinema. Originally made in 1959, the movie had never been released because Wood was unable to pay his lab bills. Two decades later, some enthusiasts rescued the movie and gave it a theatrical release before putting it out on video cassette. The Bloor was packed that evening, with the crowd in a party mood. Seeing a pristine print on the big screen, featuring the quintessential Wood cast (Tor Johnson, Duke Moore, Tom Mason, Paul Marco and, of course, Criswell) made for a great evening with the audience fully appreciating Wood’s amazing dialogue and, should we say, sparse visuals. It was a real privilege to be there, but despite the crowd’s enthusiastic response Ed himself (who had died just four years earlier) would probably have been pained by the laughter. That’s the nature of the fraught relationship between “bad” filmmakers and the people who love them.

Comments