Late summer viewing 2014, part two

Byzantium (Neil Jordan, 2012)

Amidst all the violence and cheese I’ve been watching through the past few months, there have been some more interesting, even demanding movies. Neil Jordan’s Byzantium (2012), for instance, something I had assumed from the few reviews I’d seen would be a weak retread of his already not terribly impressive Interview With the Vampire. Jordan has always been a bit hit-and-miss, but there have been times when I’ve liked his work against the critical consensus. Case in point, In Dreams (1999); co-written by Jordan and Bruce Robinson (Withnail & I), In Dreams transforms a serial killer story into a visually ravishing experience with echoes of the psychological reconfiguration of Grimm-like folktales which Angela Carter brought to her re-reading of Little Red Riding Hood in The Company of Wolves. Jordan has returned a number of times throughout his career – with varying degrees of success – to this kind of revisionist fairy tale (The Company of Wolves, Ondine, even The Butcher Boy), not magical realism but something more mythic.

Byzantium, adapted by Moira Buffini from her own play, is a much more interesting rethinking of the vampire myth than Jordan’s erratic attempt to tackle Anne Rice’s unwieldy Interview With the Vampire. In Byzantium, bloodsuckers are de-romanticized (the word “vampire” is not used, and instead of fangs these creatures have knife-like thumbnails which they use to slice open their victims’ veins); the story of Clara (Gemma Arterton) and Eleanor (Saoirse Ronan) becomes a feminist critique of patriarchal privilege in which the two women (whose relationship is complex and psychologically rich) struggle to survive in a world dominated by an ancient secret society of male bloodsuckers which finds the idea of women with their powers abhorrent. Like Jordan’s other fantasies, the film is full of striking imagery which combines moments of beauty with others of shocking violence, and in this story of Clara and Eleanor, he has made one of his strongest movies yet.

*

The Shout (Jerzy Skolimowski, 1978)

Jerzy Skolimowski’s The Shout (1978) is pretty much the opposite of Byzantium in every respect. Adapted from a short story by Robert Graves, it introduces a possibly supernatural intrusion into a quiet English village where Anthony Fielding (John Hurt), a sound artist, and his wife Rachel (Susannah York) have slipped into complacency, with Anthony indulging in a flirtatious relationship with a married woman (Carol Drinkwater). Into their lives comes Crossley (Alan Bates), a strange, menacing drifter who invites himself into their home and – thanks to their English politeness – gains power over them. All of this is related by Crossley himself to Graves (Tim Curry) during a cricket match on an idyllic summer afternoon. As we gradually learn that the match is being played between villagers and the inmates of an asylum, the reliability of the story being told becomes increasingly problematic. Skolimowski plays skillfully with this uncertainty as elements of the story keep shifting; is Crossley mad (at the film’s opening we see clearly that he’s not actually one of the inmates) or does he really have the power he claims, learned from Australian aborigines, to be able to kill with a shout? The film is permeated with intimations of supernatural power and yet in the end we only have the possibly-mad Crossley’s word that anything in the story is true. The Shout, which belongs with other mid-’70s British films like Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (1973) and Stephen Weeks’ Ghost Story (1974), is literate, sophisticated, disturbing, at times very funny … all of which make it very hard to pigeonhole, which may explain why it got a fairly limited release in 1978 and all but disappeared until its release on Blu-ray in England this past September as part of Network’s The British Film series.

*

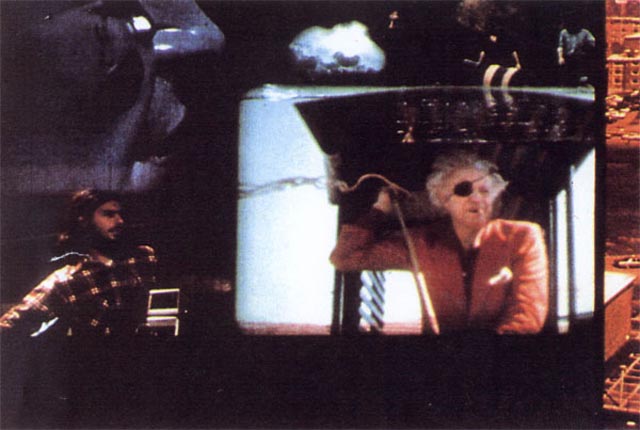

We Can’t Go Home Again (Nicholas Ray, 1973)

Very different again is Nicholas Ray’s final film, We Can’t Go Home Again (1973, 1976?), an experimental work made over a period of years with his students at Harpur College, SUNY Binghamton. This film is more about the process of its own making than the (minimal) narrative content, a kind of fictionalized account of Ray and his students making a movie about their own life and times. Without benefit of digital technology, Ray layered the images by using multiple projectors and re-shooting off a screen. The overall impression is one of chaos and contingency, the long drawn-out shooting taking its emotional and physical toll on both director and crew. But while it’s interesting as an artifact, a kind of shattering of the formal elegance of much of Ray’s previous work, it’s a bit of a slog to sit through, seeming to embody the self-indulgence of the kids who worked on it. More interesting is Susan Ray’s documentary Don’t Expect Too Much (2011), included on Oscilloscope Laboratories’ Blu-ray of We Can’t Go Home Again; this account of Ray’s life and work (and the way the two intersected) contains an account of the feature’s production which just goes to show that sometimes process is more interesting than product.

*

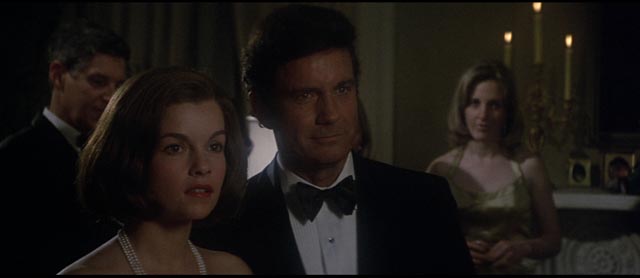

Obsession (Brian De Palma, 1976)

If any one film justified the accusation that Brian De Palma wanted to be Hitchcock, it would be Obsession (1976). While many of his films include visual references, plot devices, camera and editing techniques borrowed from Hitchcock, Obsession – as attested by both De Palma and co-writer Paul Schrader – is a deliberate attempt to create a new Vertigo. There’s the obsessed man, the dead lover, the lover’s identical doppelganger with whom he tries to recreate a romance cut short by violence. What there isn’t is a lot of plot logic and plausible character motivation. Vertigo, I must admit, is a film I can’t say I particularly like; but it is endlessly fascinating and each time I watch it (perhaps as many as ten times in various formats since its theatrical re-release in the early ’80s), it surprises me because the intricacies of the plot and the richness of the characters keep it fresh – depending on my mood, I’ll find my sympathies shifting from Scotty to Judy and back to Scotty again. Seen from Judy’s point of view, Scotty is ultimately the film’s monster; seen from his point of view she does terrible things to ruin his life. Hitchcock’s skill keeps viewer identification oscillating so the film never settles into complacent familiarity.

Obsession (released on Blu-ray by Arrow Video) lacks that kind of richness, with its characters mere puppets manipulated by implausible plot mechanics. The two most interesting things about the film are the richness of its images of Florence (beautifully shot by Vilmos Szigmond) and the surprising incestuous subtext; it seems strange to think that this got past studio brass and the MPAA ratings board, but then the mid-’70s were a time very different from now. Cliff Robertson as Michael Courtland lacks James Stewart’s ambiguity; when, sixteen years after the death of his wife Elizabeth and daughter Amy in a botched kidnapping, he discovers a woman who looks just like his dead wife in the very same Florentine church where he first met Elizabeth in 1948, a woman just the same age as she was then, Courtland becomes a creepy stalker. He gives off such an uncomfortable vibe that the fact that this woman, Sandra (Genevieve Bujold), doesn’t immediately run away indicates that she’s involved in some plot against him. Which, of course, she is. De Palma is unable to make their courtship psychologically plausible, just forcing it along because that’s where the plot needs to go. The ultimate explanation (involving Courtland’s scummy business partner [John Lithgow]) is really mundane (not to say really implausible), obviously little more than a pretext for that incest theme – which the film tries both to develop and to suppress, leading to its one truly disturbing moment in the final shot as father and daughter are reunited in one of those patented De Palma circular camera moves which leaves it unclear just what the emotional content of their relationship really is.

*

Theatre of Blood (Douglas Hickox, 1973)

A more interesting homage is Douglas Hickox’s Theatre of Blood (1973), not simply because it updates the English comedy of murder with great wit and panache, but because its real subject is its star. Vincent Price found his greatest role in Anthony Greville-Bell’s literate screenplay (from a story by producers Stanley Mann and John Kohn) and he seized the opportunity with unbridled enthusiasm. Playing actor Edward Lionheart, Price manages the remarkable feat of sending up his own image as a great ham while simultaneously revealing all his range and subtlety as a performer. Having been driven to apparent suicide by the exceedingly smug Critics Circle, all of whom gave Lionheart’s final season of Shakespeare relentlessly bad reviews, the actor returns to wreak revenge by dispatching his critics one by one in ways drawn from Shakespeare’s plays. While the film is structurally similar to the Dr. Phibes movies, Greville-Bell’s script offers much more than a string of inventive murders; the plot is firmly rooted in character, with Lionheart successfully preying on each critic’s vanity, which prevents his victims from protecting themselves in spite of knowing that he’s out to murder them. The deaths are gruesomely funny, each accompanied by Lionheart’s (occasionally rewritten) recitations from the Bard’s works. The cast is packed with the cream of English character actors, with victims played by Jack Hawkins, Arthur Lowe, Dennis Price (a nice echo of Ealing’s classic Kind Hearts and Coronets), Coral Browne, Robert Coote, Harry Andrews, Robert Morley and Michael Hordern. Although a viewer might feel a little disappointed that the Circle’s smug chairman (Ian Hendry) manages to survive in a sop to moral convention, the script’s ending seems apt with Lionheart’s choice of Lear tragically backfiring on him. The one misstep in the otherwise impeccable script is the unnecessary and (given Lionheart’s motivation for the murders) unjustified death of Eric Sykes’ policeman, Sergeant Dogge. Arrow’s lush Blu-ray does full justice to Wolfgang Suchitzky’s photography, entirely shot on wonderful London locations, and the film is so well-made that it doesn’t seem to have aged at all.

Comments