Video Nasties Revisted

Five years after making the excellent documentary Video Nasties: Moral Panic, Censorship and Videotape, Jake West presents a follow-up which may lack the full impact of his original dissection of the hysteria which gripped Margaret Thatcher’s Britain in the early 1980s, but is nonetheless a fascinating examination of the social and political consequences of the passage of the Video Recordings Act of 1984. Much of it deals with the process of moral (as opposed to political) censorship, clearly rooted in class prejudice (we intelligent people can look at this rubbish without harm – merely an offense to taste – but the weaker minds of the working class risk corruption and incitement to heinous criminal behaviour). The uses to which a reactionary government and its agents put that poorly devised law make for an interesting illustration of the conflicts between popular culture, individual freedoms (and taste) and a class-directed urge to control and shape a population feared by its ostensible “rulers”.

The theme which runs through Video Nasties: Draconian Days (2014: Nucleus Films, Region 2 DVD) is the arbitrary nature of that political power. Having drummed up hysteria about the dangers of “evil” movies viewed in the privacy of the home (with the supposed risk of damaging children’s minds), the government and the press eagerly pounced on any and every sign of aberrant behaviour which could be attributed to the influence of home video. When in 1987 Michael Ryan shot sixteen people in Hungerford, wounded fifteen more, and then killed himself, the fact that he wore a bandana during what was dubbed “the massacre” had the press in a frenzy blaming First Blood (Ted Kotcheff, 1982), the Sylvester Stallone movie about a persecuted Vietnam vet who finally turns on those who torment him. The fact that there was no evidence that Ryan even owned a video player and was known for his obsession with weapons, including a large collection of mercenary and survivalist magazines, was irrelevant when putting the blame on a single identifiable movie could provide a quick short-hand “answer” to the troubling question of motive.

Then there was the 1993 case of James Bulger, a two-year-old who was kidnapped, tortured and murdered by a pair of ten-year-old boys in Merseyside. Although the two boys, Jon Venables and Robert Thompson, were prone to truancy and petty theft and went about the murder in a chillingly methodical way with no apparent motive other than to see what it was like to kill a child, the press jumped on the fact that Venables’ father had rented Child’s Play 3 (Jack Bender, 1991) a few months before the crime. Suddenly, this mediocre horror movie became the indisputable “cause” of the boys’ actions and the old moral panic was reignited. As with all moral panics, the underlying impulse was to find a single comprehensible cause for social phenomena which threatened an always precarious stability. Banning violent movies would be so much simpler than confronting complex, seemingly insurmountable social problems.

There were two main elements to this attempt to suppress “dangerous” movies: the police and courts, and the British Board of Film Censors (changed to Classification in 1985). West’s documentary focuses on both approaches, revealing just how arbitrary and futile this kind of moral censorship will always be (as opposed to political censorship, which governments often indulge in with some success). One of the key figures in the film is James Ferman, the American-born Director of the BBFC from 1975 to 1999. The BBFC was one of the most active and stringent censorship agencies in the Western democracies, its aim often the reinforcement of Britain’s entrenched class system. As is clear from many of the interviews in the film, both with former censors and those who opposed the Board, there was always an implicit belief that while the well-educated and intelligent class could view this disreputable material with impunity, the weaker minds of the lower classes were always vulnerable to the dangerous influence of crass pop cultural products. Interestingly, a number of archival clips from various television talk shows and debates reveal that these moral guardians tended to be rude and intolerant, refusing to allow calm, reasonable anti-censorship speakers to voice their opinions without loud, arrogant heckling, revealing an odd mixture of absolute certainty and deep insecurity about their position.

It’s also apparent that these would-be guardians – largely due to their revulsion and disdain – were more apt to be unhinged by depictions of graphic violence and horror than those they were trying to “protect”. The censors’ and politicians’ inability to distinguish between reality and fantasy (seeing in the crudest, most inept gore films examples of genuine “snuff”) caused them to see greater degrees of danger than were warranted: as filmmaker Chris Smith (Creep, The Black Death) points out, the advent of video with its power to endlessly rewind and replay actually diminished the initial impact of disturbing material by making it possible for the viewer to establish an intellectual distance from that first emotional response and see just how the visual tricks were performed. The fans ended up with a much more sophisticated understanding of movies, how they are made and function, than the people who had appointed themselves to control what could be seen. (The inadvertent consequences often produced by attempts to censor go back at least as far as James Whale’s Frankenstein [1931], where the scene between Karloff’s monster and the little girl he briefly plays with was cut short because the monster’s action at the end of their game of throwing flowers into the lake to watch them float was considered too disturbing; with no flowers left, the Monster picks up the girl and tosses her into the water, puzzled when she doesn’t float like the flowers, but instead sinks to her death. In the version cut for censorship reasons, the scene ends with the smiling Monster reaching for the girl, followed by the sight of her distraught father carrying her body into the town square … leaving the viewer to fill in a far more disturbing reading of what happened.)

As Ferman’s tenure went on, he increasingly moved beyond mere censorship towards an effort at social engineering, altering the records of decisions made by the Board’s examiners, even physically cutting films submitted for classification (he fancied himself a better filmmaker than the people who made the films submitted to the Board); tensions between Ferman and his examiners led to him firing the lot, and finally unilaterally ending the prohibition against pornography (a less harmful diversion than violence) without bothering to consult his masters in the Home Office.

Interestingly, almost immediately after he left his job at the Board a string of previously banned movies were given video releases in Britain – including The Exorcist, which was one of his personal obsessions. But more than horror, Ferman was concerned with the display of weapons on screen, particularly knives and various Asian martial arts accessories (nunchuks and Ninja stars), which led to such oddities as the heavy censoring of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles movies.

But while the officials of the BBFC struggled to find some kind of coherent response to violence, horror and sex, the police and prosecutors ran rampant in completely unpredictable ways, seizing and destroying tapes and prosecuting street corner video rental store owners seemingly at random. No one in the business could ever be sure that what they were stocking was legal or not because cases were brought on an ad hoc basis, triggered by individual police officers’ judgments of what might be offensive. There were fines and even jail sentences for simply stocking a tape with an excessively gruesome cover.

This led the industry to attempts at self-policing with regard to packaging, awarding or withholding a seal of approval based on what was printed on the video cases; inevitably there was a tension between the demands of commerce (renters were attracted to the more extreme packaging) and fear of authoritarian crack-downs. The inherent uncertainty created was a clear sign that the whole project of social control was misguided. Laws arising from questions of personal taste are doomed to cause havoc because taste is in constant flux. Films which had played theatrically with BBFC approval were severely cut and in some cases even banned on home video – again because the issue was one of control: a theatrical audience can be more or less monitored, while a home audience could not … and “the children must be protected”. There were even prosecutions for blasphemy, cases rooted in outmoded religious laws hundreds of years old.

The story reaches levels of absurdity with James Anderton, Chief Constable of Manchester, who was on a mission from God to clean things up. Literally. Anderton claimed that God spoke directly to him (as one interviewee in the documentary points out, when Charles Manson claims to hear God’s voice, we immediately label him a psychotic; when the Chief Constable hears God, the British popular press jump on board the crusade.)

Inevitably, all these efforts at suppression produced a vibrant and active underground, a sub-culture which sought out, duplicated and traded forbidden titles. West even has footage of a police raid on the home of one such fan, bagging up all his tapes and seizing his multiple VHS players because they’ve been used in the commission of a crime … all while the resigned young man asks how much longer it’ll take as he has to get to work. The scene is rather poignant in its depiction of the stupidity of trying to police social rather than criminal behaviour. In fact, these efforts tended to inflame the very thing they were trying to suppress, creating a demand for these products (often accompanied by feelings of disappointment when forbidden titles turned out to be boring crap); the murky, multi-generation videotapes added to the sense of illicitness, the thrill of rebellion which merely increased the sub-culture’s love of sleazy and sordid movies. There’s no better publicity than a ban to boost interest.

As with Nucleus Films’ release of the first Video Nasties documentary, one of the appeals of this second volume is the extensive collection of supplementary material. Once again there are two additional disks containing more than nine hours of trailers with introductions by critics, filmmakers and academics; on the original release these were for the thirty-nine official “nasties”, plus an additional thirty-three titles which weren’t on the list but nevertheless were frequently prosecuted by local authorities. This second volume gives us the “Section 3 list”, which was discovered in the files during research for the first film. These were films flagged under the Obscene Publications Act and also liable to seizure although not prosecution; they were likely to be dealt with in magistrates court, that is as a civil matter requiring perhaps a fine along with the destruction of the tapes, but not with a criminal conviction.

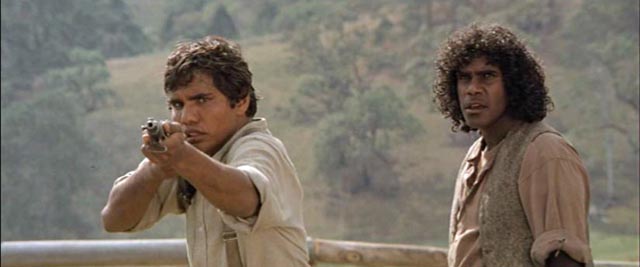

Once again these titles reveal just how contingent and arbitrary the whole exercise was. (The complete list can be found here.) Among the slasher, cannibal and giallo movies can be found John Carpenter’s The Thing (what antisocial behaviour was likely to be inspired by that?); Wes Craven’s The Hills Have Eyes (cannibalism is always a threat); Jack Hill’s Foxy Brown (encouraging the underclass to stand up and defend itself?); George Romero’s artful gloss on vampire myth, Martin, as well as his outrageous Dawn of the Dead; Don Coscarelli’s adolescent fairy tale Phantasm; David Cronenberg’s Rabid and Scanners; and perhaps most inexplicably Fred Schepisi’s The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith … or perhaps not so inexplicable given the underlying political/class intent of the whole enterprise as Schepisi’s film is an angry account of the genocidal racism underlying the formation of Australia and by implication a justification of the oppressed rising up and attacking the oppressor; that is, an expression of the very things feared by an establishment which distrusted its own lower classes.

Comments