The Complete Jacques Tati on Blu-ray

Christmas has come early this year, courtesy of The Criterion Collection. With their seven-disk Blu-ray set of The Complete Jacques Tati, they’ve gathered together all six features of one of the key French filmmakers, plus a wealth of supplementary material, including a collection of Tati-related shorts and numerous documentaries and visual essays about the director and his work. Criterion have outdone themselves with this exhaustively generous set.

Comedy is often so culturally specific that it has difficulty crossing national boundaries. Sound comedy, that is; silent comedy has a more universal appeal, rooted in human behaviour rather than language. Tati, perhaps more than any other filmmaker, managed to harness the forms of silent comedy within the sound era, his rich and complex soundscapes sublimating language as one aural component among many; language in Tati’s films takes on an almost abstract, poetic form designed to enhance moods and highlight difficulties in comprehension which create obstacles to communication. Much of the comedy in Tati’s films arises from misunderstandings which constantly threaten the social glue which holds communities together.

…and restored to colour (1995)

In a larger sense, Tati wants us to learn new ways of seeing in order to come to an understanding of the world we inhabit. Like all great filmmakers, he demands that the audience come to him rather than sit back and wait for him to hand them an experience; his films demand our engagement, and in a sense we have to learn what it is that he’s doing in order to appreciate and enter the increasingly monumental game he played throughout his career. To some degree, this makes his films an acquired taste, but for those who acquire that taste, his six features seem inexhaustible in their invention and insight.

My own relationship with Tati’s films has not been constant. My first experience was seeing Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday when I was five or six; it was a delight because it captured the childlike essence of a holiday by the sea, something connected with my own experience. And yet, when I saw it again years later, I was puzzled that it didn’t revive that original feeling in me; there were other things going on in the film beyond that first simple layer and I wasn’t prepared for the deeper – and darker – feelings the film triggered in a more mature viewer.

My next experience was seeing PlayTime in London in, I think, 1975. I was mesmerized by the large images (the film was famously shot on 70mm, something which conceptually seems antithetical to the idea of comedy), which somehow combined a seemingly simple clarity of design with an endless complexity of detail. It left me with a cool sense of admiration, but it didn’t strike me as funny. What finally re-engaged me with Tati’s work was seeing Mon Oncle for the first time, on its surface a much simpler film than PlayTime, but for that very reason it allowed me to grasp what Tati was doing and, in its small domestic details, I came to appreciate both the intellectual underpinnings of his films and the great human warmth which rises out of them.

When I got to see PlayTime again, it suddenly seemed both one of the greatest and one of the funniest films ever made, a feeling which has only increased with each subsequent viewing: here, Tati encompasses a whole world of human experience, every detail of which is instantly recognizable as something we’ve always known but seldom bothered to take note of before … like the greatest art, it makes us aware of what we have already seen but remained largely unconscious of. This in fact is the most enduring effect of his work, that we come out of his films to discover that the world we live in is “Tati-esque”, full of details of design and human behaviour which are strange and funny when we do finally take note of them.

… and his sister’s house

Tati’s films, beginning with Jour de fete and climaxing with Playtime, become increasingly Modernist. In Jour and Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday, he creates communal portraits (sometimes criticized for their conservatism), swirling carnivals of social activity barely centred on, in the first, Francois the postman and, in the second, Hulot himself, the great creation about which Tati had enduringly conflicted feelings. Francois is highly verbal, an integral element in the life of the village whose business his job allows him to know intimately. Hulot remains largely unconnected to the people around him in the small town by the sea, yet his presence constantly disrupts those people’s activities.

In Mon Oncle, for the first time, Tati addresses the impending future rather than a past which seems to be slipping away under the tide of “progress”. It’s clear that he was troubled by what he saw in France’s burgeoning post-war development. Much of the film takes place in and around the stark Modernist house and garden of Hulot’s sister and brother-in-law. Tati is richly inventive in laying bare the absurdities of this middle class pretension, which is contrasted with the less orderly life of the town square and Hulot’s asymmetrical apartment building. The obsession with appearance and possessions which cramps the lives of his sister and brother-in-law is offset by the warmth of Hulot’s relationship with their son, a connection rooted in shared experience rather than material things.

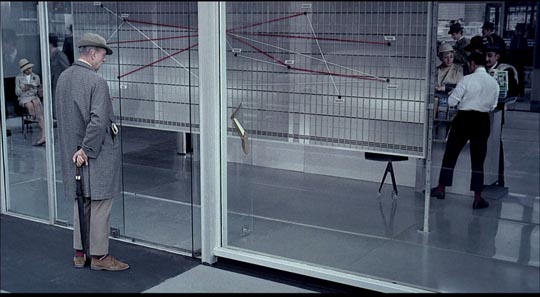

These ideas are almost infinitely expanded on in PlayTime, whose theme is the ways in which we construct environments antithetical to human scale and experience … and how the irrepressible assertion of human idiosyncrasy and unpredictability causes these social machines to malfunction and re-conform to a more human dimension. The tension in Tati’s work is between who we are and what we (so often mistakenly) aspire to. This tension is embodied in the very conception of PlayTime, with its fascination with the Modernist city echoed in the monumental machine-like precision of the film’s construction, which paradoxically is dedicated to the disruption, even destruction, of the inhuman environment.

Feeling somewhat trapped by the popularity of Hulot, Tati makes every effort to lose himself in PlayTime, filling the film with false Hulots which serve not only to take the attention off himself but also to emphasize the increasing anonymity of the individual in a modern city.

The most expensive film made in France up to that time and a relative failure commercially, PlayTime resulted in virtual financial ruin for Tati and personal disappointment in the apparent rejection of his creative aims. Although the film has subsequently become recognized for the masterpiece that it is, Tati’s subsequent career bears the marks of the film’s failure. Even for this prodigious talent, topping the achievement of PlayTime would have been a daunting prospect even if it had been a hit; his final theatrical feature, Trafic, released four years later, is a shadow of its predecessor, certainly full of inventive details, but looking something like a footnote as it expands on the imagery of traffic which runs through PlayTime as a metaphor for the mechanical rhythms of urban life.

His final work, Parade, made for Swedish television, is a coda which harks all the way back to his origins in mime and variety; shot on a mixture of film and videotape, it presents life as a circus performance, with Tati taking obvious pleasure in revisiting his old routines and interacting with a live audience before quietly leaving the stage in the hands of young children who spontaneously play with the array of props littering the studio set.

While Tati’s work is full of pleasures both large and small, it doesn’t conform to standard comic devices. As David Cairns points out in an essay in the booklet accompanying the set, Tati doesn’t create conventional gags. I think this is why PlayTime left me cold the first time I saw it; it doesn’t behave like a traditional comedy. Rather, Tati’s comic moments are about the process of their own construction (allowing him more often than not to dispense with a punchline): we see him building an effect moment by moment until our anticipation of where it will lead becomes the source of humour — and pleasure. I have a friend, a filmmaker and teacher, who doesn’t like Tati and this is one of his major complaints; he insists that this foregrounding of process works against comic effect (as I mentioned, Tati is perhaps an acquired taste!). For the director’s admirers, these films, rooted in a brilliant observational sensibility, are about the ebb and flow of life, the rhythms of social behaviour punctuated by idiosyncratic personal details. They open our eyes to the world we live in and make our own experience of that world that much richer.

The disks:

There’s really too much in this set to talk about in any detail. The transfers of the features are as fine as we have come to expect from Criterion, although there is some variation in the quality of the alternate versions of some of the films.

Jour de fete (1949)

There are three versions of Tati’s debut feature: Initially, Jour de fete was to be the first home-grown colour film, using a French-developed process called Thomson Colour. But the company which invented the process abandoned it before perfecting a printing process. The original 1949 release (1:27:19) was created using the black-and-white negative from back-up cameras which had been used in case the colour version didn’t work out; this is beautifully restored, with rich contrast and detail. The revised 1964 version (1:20:31), with the addition of an entirely new character (an artist who observes and sketches events in the village) and hand-tinted elements which re-introduce hints of Tati’s original colour conception, is also mostly excellent, although all shots using the added colour are slightly darker, with weaker contrast because of the optical process involved. Finally, the recovered colour version from 1995 (1:20:15), offering a third, slightly different edit (removing the artist as an unnecessary element), has the look of a hand-tinted film from the silent era; this has the weakest image of the three, but is nonetheless invaluable as an indication of Tati’s original intentions.

The set’s most interesting special feature is included on this disk: In Search of the Lost Colour (30:05), a 1988 episode of the French television program Cinema cinemas, offers a fascinating technological detective story in which the Thomson Colour process is reverse engineered to finally create a screening print of the colour version. This involves not only recovering the (almost lost) original negative, but figuring out how the “waffle-pattern” film stock was designed, tracking down the actual camera and lenses on which the film was shot and then perfecting the printing process which the original company had never actually managed to figure out before abandoning the format in an agreement with Technicolor, essentially voluntarily removing themselves from competition with the American company.

The disk’s other supplement is A l’americaine (American Style), a feature-length (1:21:07) visual essay by French critic Stephane Goudet analysing the influence of American post-war modernity on the reshaping of French society, as reflected in the pressure for modernization which propels the story of village postman Francois (Tati).

Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday (1953)

The second disk foregrounds Tati’s 1978 version of his first international success (1:28:56) in another beautifully crisp restoration. This version was re-edited (with some newly shot elements) and the soundtrack was substantially revised. The original 1953 version (1:40:05) looks a bit worse for wear, with weaker contrast and a less pristine source.

The supplements include a brief introduction by Terry Jones (3:29), who speaks of his own first experience of the film and his admiration for Tati; a detailed analysis by critic and theorist Michel Chion of Tati’s complex use of sound (31:52); an episode of Cine regards from 1978 (26:37), which also deals with Tati’s use of sound, the deliberate banality of the dialogue in his films as a facet of their realism, and the ways in which sound design brings life and character to the images; and Clear Skies, Light Breezes (40:24), another visual essay by Stephane Goudet.

Mon Oncle (1958)

There are two versions of Tati’s third feature, the French Mon Oncle (1:56:25) and My Uncle, the simultaneously prepared English-language version (1:50:28), both in excellent transfers. Tati made the alternate version because he disliked subtitles as a distraction for the audience and he now had a definite aim to send the film out to the American market.

Once again, Terry Jones leads off the supplements with a brief personal introduction (5:10). This is followed by Once Upon a Time … Mon Oncle (51:37), a 2007 program by Marie Genin, Serge July and Camille Clavel which interviews a number of Tati’s friends and collaborators, as well as others, including Tati fan David Lynch; this documentary is full of interesting observations about the filmmaker. Next, Everything Is Beautiful from 2005 is a three-part examination of the crucial use of design in Tati’s work (52:46). Everything’s Connected (51:37) is another visual essay by Stephane Goudet, while Le Hasard de Jacques Tati (8:32) is a brief television segment about Tati’s dog Hasard (Chance), which leads to the story of the dogs used in Mon Oncle which were rescued from the pound and for which Tati found homes after the production ended.

PlayTime (1967)

Transferred in 6.5K from the original 70mm negative and restored in 4K, Tati’s masterpiece looks spectacular on Blu-ray – and yet its use of wide shots and crowded frames still demands a big screen; no matter how good the transfer, one knows that a great deal is being missed even on a large HD screen. Complex frames with multiple points of focus and different parts of the screen interacting with one another in unexpected ways make this a film which seems perpetually fresh and inexhaustible; the use of architecture and the ways in which human figures interact with their man-made environments are perhaps unequaled in cinema (even by Kubrick). The almost hour-long restaurant sequence which comprises the second half of the film is one of the richest compendiums of comic detail available on film and the finest expression in Tati’s work of the human retaking possession of a world under constant threat of dehumanization.

The supplements, beginning with another Terry Jones introduction (6:17), include fascinating archival footage of the production in “Tativille”, an episode of a British television program called Tempo International (26:10), in which filmmaker Mike Hodges interviews Tati at his studio, and Beyond PlayTime (6:30), a brief piece written by Stephane Goudet about the construction of the city set and its subsequent destruction when the film was finished. An interview with script supervisor Sylvette Baudrot (12:10) offers observations about Tati’s method of directing actors and his meticulous attention to detail (which prompted reshoots of scenes to address small but crucial details). Like Home (18:55) is another visual essay by Stephane Goudet about the film, in which he quotes Tati’s opinion that cinema needs to be freed from the expectations arising from plot so that space and time can be opened up to allow viewers to fully experience and appreciate individual moments. Jacques Tati at the San Francisco Film Festival (16:44) is an audio recording of a Q&A session following the first U.S screening of PlayTime in which he addresses his troubled relationship with distributors (the 124-minute cut of the film we now have was edited down from a 153-minute premiere version).

PlayTime is the only film in the set with any commentary, in the form of remarks on selected-scenes by Philip Kemp (46:44), Stephane Goudet (13:04) and Jerome Deschamps (13:14).

Trafic (1971)

Tati’s final theatrical feature seems a bit like the orphan of the set. The transfer is excellent, but the many voices which offer context and analysis for the other films here fall silent. The only extra is a 1976 episode of the BBC series Omnibus, Jacques Tati in Monsieur Hulot’s Work (49:28) in which Gavin Millar interviews the director about his entire career on the beach at Saint-Marc-sur-Mer, the location of Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday. No essay by the otherwise omnipresent Stephane Goudet, nothing specific to Trafic itself other than a trailer.

Parade (1974)

Given the mix of sources – shot on 35mm, 16mm, super-16mm and video – the transfer of Parade offers a sharp and colourful image. This production for Swedish television inevitably lacks the scale and visual precision of the features; the focus here is on the various variety acts and Tati’s own mime performances, but that content is rich and varied; in a strange way, the technical limitations help to foreground the air of melancholy which runs just below the surface of all the features, giving Tati’s surrender of the stage to the young children at the end a poignant sense of final departure. Here, after a long career filled with triumphs and disappointments, Tati turns the future of entertainment over to a new and as yet unformed generation.

The supplements are led off by In the Ring, another visual essay by Stephane Goudet (28:06). An Homage to Jacques Tati (15:00) is a reminiscence by Tati’s friend and artistic collaborator Jacques Legrange made for the French television program Magazine; Legrange comments on the criticism Tati faced for being over-meticulous, for taking too long to make his films, but points out that this was key to achieving the observational accuracy which was essential to the filmmaker’s comedy. Finally, In the Footsteps of Monsieur Hulot is a two-part documentary by Tati’s daughter Sophie Tatischeff (51:18, 52:02) surveying her father’s entire career and the genesis and evolution of his beloved character, Monsieur Hulot.

Tati Shorts

The seventh and final disk in the set collects seven short films in which Tati appeared, wrote and/or directed. The three from the ’30s reveal a performer not yet fully developed. In On demande une brute (1934, 25:01), written by Tati and Rene Clement, directed by Charles Barrois, the tall thin Tati plays an actor with an impatient wife, who pushes him to apply for a job which turns out to be wrestling a particularly violent champion; the print is quite battered and scratched and the sound muddy. Gai dimanche (1935, 21:30), directed by Jacques Berr, has Tati and a performer called Rhum (who wrote the script with Tati) renting a vehicle to provide a tour out to the country for a group of people on a Sunday afternoon; this print is in better shape. Soigne ton gauche (1936, 13:23), written by Tati and directed by Rene Clement, has the actor as a farm-worker who’s drafted as a sparring partner for a boxer; like On demande une brute, this short builds on Tati’s signature sports-themed mime routines. None of these early films display a great deal of cinematic flair and much of the comedy is limited to the visual oddity of Tati’s long, thin frame.

L’ecole des facteurs (1946, 16:05), Tati’s directing debut, marks a huge advance. This brief film about a village postman training in “new methods” shows not only that Tati had great skill in building a gag, but more importantly for what would soon follow, that he had a superb eye for behavioural tics. This film was the kernel for what would develop two years later into Jour de fete (and one or both of them were obviously the source for the opening dream sequence in Tim Burton’s Pee Wee’s Big Adventure [1985]).

Cours du soir (1967, 28:36), directed by Nicolas Ribowski, was shot at the PlayTime studio, using some of the sets from the feature, and is built around an evening class in which Tati teaches some of the fundamentals of his comedy to a room full of students. Once again, this is rooted in Tati’s observational skills and the way in which he can transform what he sees into finely-tuned bits of physical business.

Degustation maison (1977, 13:58) doesn’t actually involve Tati himself, but this short directed by his daughter Sophie Tatischeff was shot in the bakery in Sainte-Sévère-sur-Indre, the town which served as the location of Jour de fete. The influence of Tati is evident in the lively and crowded non-story, in which a variety of people come and go, eating a lot of pastries as they chat inconsequentially and flirt with the woman behind the counter.

Forza Bastia (1978, 27:37) is unusual in that it’s actually a documentary – about a town in Corsica reacting to the first time its football team has reached the final of the European Soccer Cup. Directed by Tati, it was left unfinished until Sophie Tatischeff completed it in 2000. We don’t see the game (between Bastia and Eindhoven), but rather the whole town’s building anticipation and excitement, the tension of the spectators and the eventual disappointment of a loss. The film is full of glimpses of the kind of behaviours which served as the source of Tati’s comedy and the forces which thwart human intention (a sudden downpour floods the field and workers get out with mops and buckets to try and make it possible for the game to continue).

The disk includes two supplements, both by Stephane Goudet: Tati Story (2002, 20:38), a brief account of Tati’s life and work, and Professor Goudet’s Lessons (2013, 31:27), a series of chapters analysing various aspects of Tati’s art, including the use of sound, the critique of Modernism (which Goudet asserts has nothing to do with a reactionary desire to return to a “simpler” past), and the complexity of Tati’s observations – which he compares to the paintings of Breughel, with their dense multiple points of action. Goudet sees Tati’s mission as training his viewers to explore the world around them, to discover its richness, and to see the humour in all things human.

The booklet accompanying the set contains essays by James Quandt, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Kristin Ross and David Cairns.

Comments