Boxed in … the urge to collect

If it was just about the movies, we’d all be happy with plain disks in cardboard sleeves with a title printed on the front. Or with video streamed off Netflix or Apple TV, its only lingering trace in the “movies you’ve watched” list on the site. And for many people, of course, that really is enough. But for anyone with a collector’s sensibility (or is that pathology?), there’s always something more. Even before the arrival of home video in the late ’70s, when the only option was to catch a movie in the theatre, or screened on television (always pan-and-scanned and interrupted repeatedly by annoying commercial breaks), the collecting impulse could manifest itself in a number of ways. If you were rich, you could actually accumulate a collection of film prints; if you had less money, there were those 8mm condensed versions of movies that you could order from ads in the back of comic books or magazines like Famous Monsters of Filmland. These options required the equipment to project. More convenient – and the path I followed – was buying substitutes for the films themselves: books about film, copies of scripts and posters – devices to maintain a connection with movies which had provided a transient experience, passing through and lingering only in memory.

Once home video arrived, it became possible to actually own a copy of the movie itself, to watch as many times as you’d like (until the tape wore out). This altered our relationship with movies in a radical way. Where before we had possessed an experience, something which became encoded in memory (and as often as not distorted in various ways – how many times have we seen again a movie from long ago which turns out to be nothing like our memory of it?), now we were able to possess movies as objects at a reasonably affordable price. It seems oddly naive, looking back, how precious those early video tapes were … as technology has advanced exponentially in the subsequent forty-odd years, those old VHS copies of favourite movies are now virtually unwatchable, mere shadows of the films they were transferred from.

As time passed and possessing movies became increasingly routine, the simple thrill of owning them began to wear off. We wanted more – first of all, transfers in the correct aspect ratio to put an end to the severe cropping of the image. And then better, sharper, more accurate transfers. As always with things technological, I was a late adopter: I got into laserdisk collecting just a few years before the advent of DVD. But, apart from the undoubted benefits of improved image coding, laserdisks offered other attractions. As objects, they were more attractive than VHS cassettes; they had weight and presence and, most importantly, they allowed for supplemental materials in a way that VHS was largely unable to provide. There were image galleries, documentaries, and most important of all commentaries on alternate audio tracks. The films themselves were no longer the sole attraction; now we had context, history, insight into the filmmakers’ intentions and creative process. Everything we’re now familiar with in the realm of digital disks was pioneered on laserdisk.

But laser was a specialist’s medium, an expensive, collector-centric format. Everything that they offered became far more accessible with the invention of DVD … and all those special additional features became more or less standard. In fact, “bare bones” disks began to feel like a bit of a cheat – we were only being offered the movie itself? That was a bit of a rip-off. The corollary of this, though, was the proliferation of mediocre EPKs offering little real value and contractually-obligated commentaries by people who more often than not had nothing much to say about the movie they had made. I always listened to the commentaries on my laserdisks and, at first, I always listened to the commentaries on DVDs. But after a while, I became more selective. Was there really any value in listening to Simon West talk about making The General’s Daughter? These days I limit my listening to tracks on movies I’m particularly interested in – say scholarly commentaries on Criterion disks, or the reminiscences of a director who had to find ingenious ways to make a genre film on a really low budget. (My listening to commentaries has actually picked up recently as I now rip the tracks and put them on my iPod, consuming them on-the-go rather than sitting in front of my TV.)

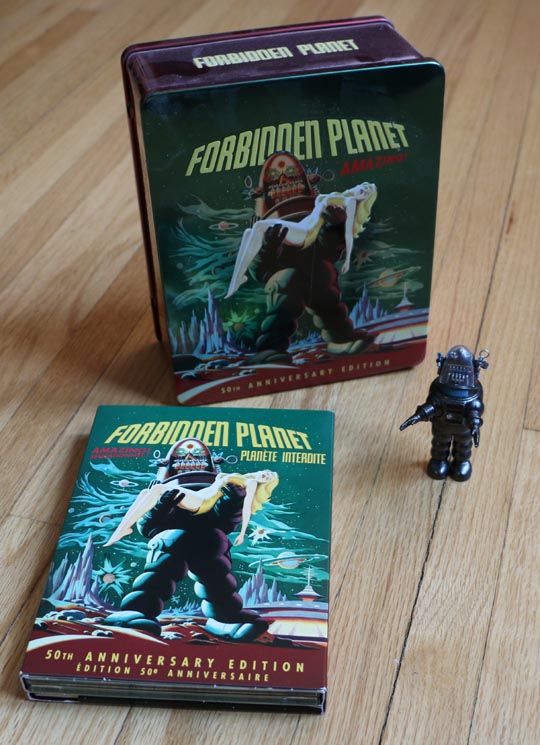

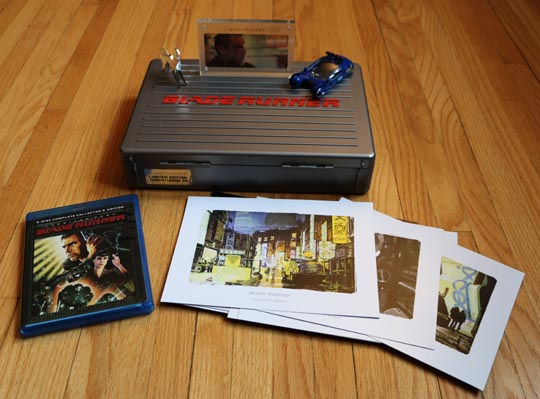

And so, in time, all the supplements, all the flashy extras, have become normalized. So where does the person with that collector’s itch go to scratch it? Personally, I look for rarities and obscurities, things a little harder to find (the Karel Zeman disks issued by the Muzeum Karla Zemana in Prague – numbers 6 and 7, The Tale of John and Mary and On the Comet, just ordered; various classics and avant-garde titles from Edition Filmmuseum in Munich, including a pair of German silents centred around soccer, Robert Reinert’s radical post-WW1 Nerven, and Hanns Walter Kornblum’s silent sci-fi epic Wunder der Schopfung; the Blu-ray put out by digital restoration company Alpha-Omega, also in Munich, of Ernst Lubitsch’s silent epic The Loves of Pharaoh; the two box sets of Korean films from the 1930s and ’40s, the period of the Japanese Occupation, released a few years ago by the Korean Film Archive under the title The Past Unearthed; the four-disk edition of Wang Bing’s magnificent West of the Tracks put out by Trigon Film in Switzerland – to name just a few). Or, conversely, I sometimes find myself drawn to elaborate special editions of more accessible films because the packaging itself appeals to me – here the physical object comes to have as much value as, if not more than, the film buried inside it.

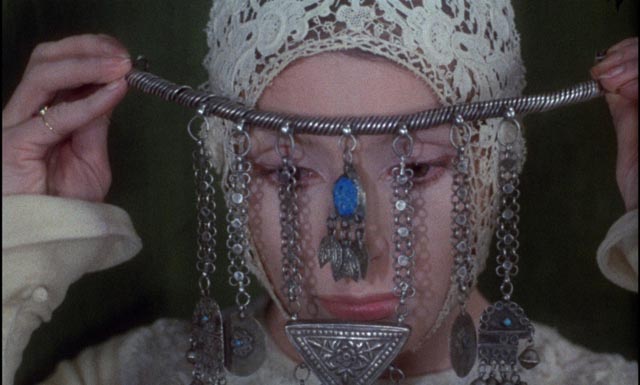

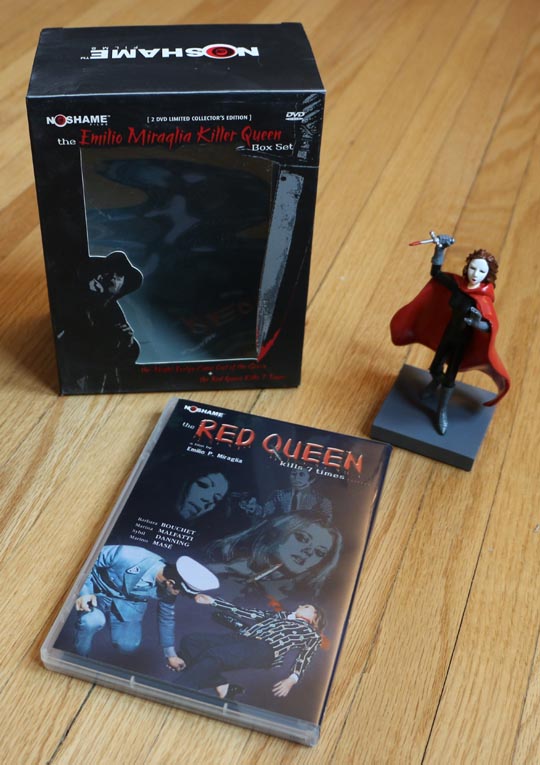

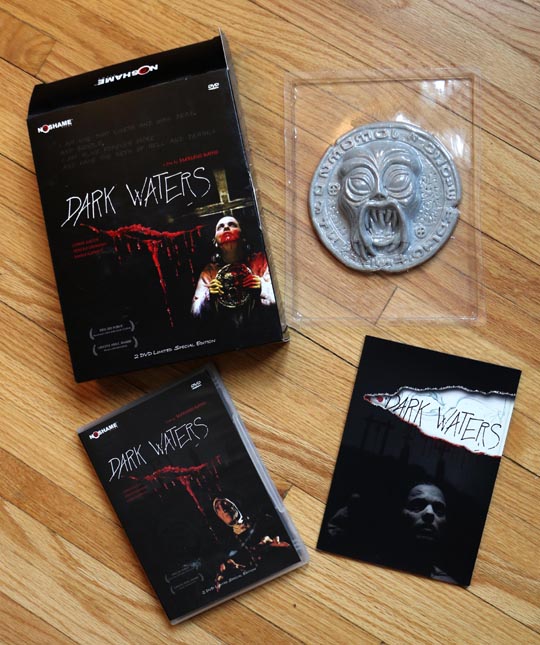

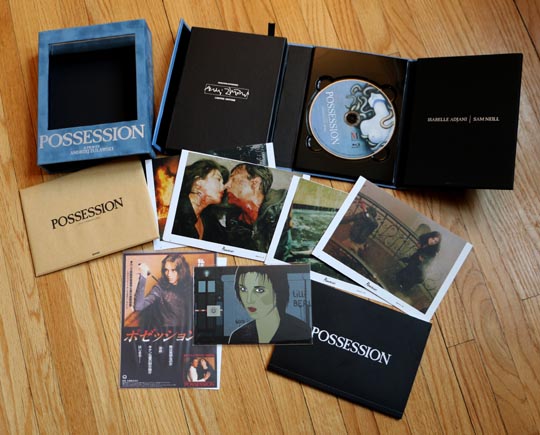

This latter category ranges from things like the hefty 20th Anniversary edition of E.T., elaborately packaged with a hardcover book and various other extras (despite the fact that I’ve never liked the movie); Blue Underground’s coffin-shaped Blind Dead Collection; the 40th Anniversary Planet of the Apes Blu-ray edition contained within a hardcover book; the extremely unwieldy Murnau, Borzage & Fox set; Fantoma’s lunchbox edition of the first four volumes of Educational Archives shorts; No Shame’s editions of Mario Baino’s Lovecraftian Dark Waters and The Emilio Miraglia Killer Queen Box Set containing a pair of gialli, The Night Evelyn Came Out of the Grave and The Red Queen Kills 7 Times, each set coming with a sculpted figure along with the disks. With the recent release of Shout! Factory’s restoration of Clive Barker’s Nightbreed, I automatically went for the more expensive limited edition, three-disk set rather than the unlimited two-disk version (#5281 of 10,000, by the way). Then there’s possibly the most niche of all companies, Mondo Vision, which is devoted to releasing the works of Andrzej Zulawski in editions supplemented with commentaries, interviews and documentaries; needless to say, as each has become available, I’ve opted for the limited edition (2000 copies) version which also includes a soundtrack CD and a book of essays, interviews and reviews: l’important c’est d’aimer (#809 of 2000), La femme publique (#740), L’amour braque (1890), Szamanka (1829), Possession (1808). While I have to admit that I don’t like all of Zulawski’s films, I’m really looking forward to Mondo’s edition of his hugely ambitious, partially crippled science fiction epic On the Silver Globe (a film which ranks with Tarkovsky’s Solaris).

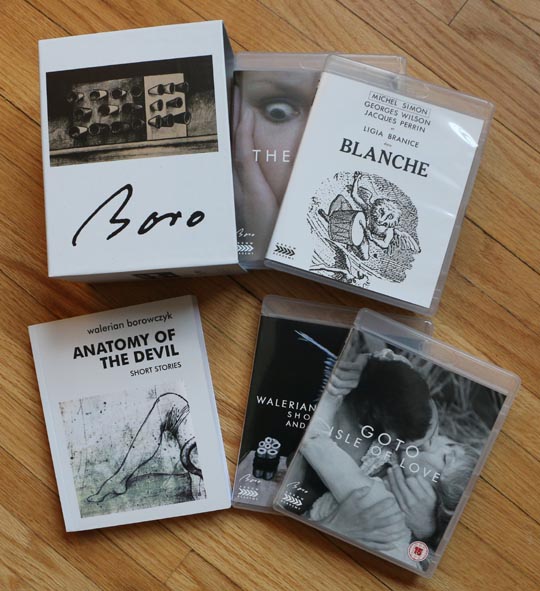

Camera Obscura: The Walerian Borowczyk Collection (1959-77)

Which brings me to my two most recent prized limited edition purchases, both from Arrow Video. I’m not sure whether Mondo Vision’s Daniel Bird is the same Daniel Bird who has produced Arrow’s recent box set of Walerian Borowczyk films, but it seems likely. The same kind of care has gone into this 11-disk, dual-format set as into those Zulawski releases, and there’s the Polish outsider-auteur connection. This set was limited to 1000 units (I got #733) and includes a substantial book with 250-odd pages of critical writing, plus a 90-page collection of nine short stories by Borowczyk.

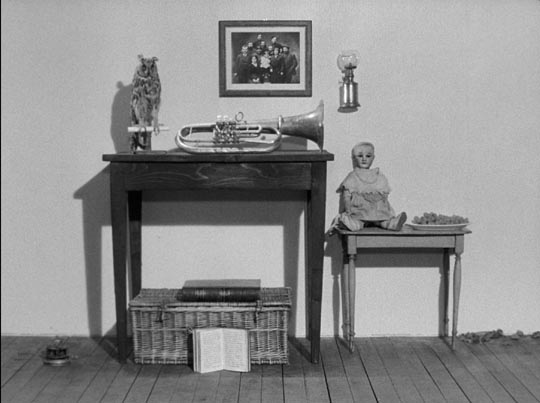

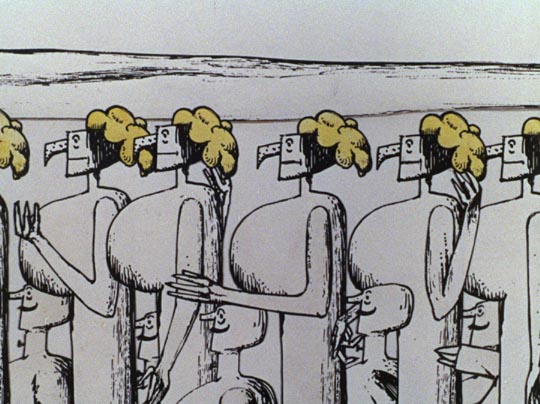

and hand-drawn: Theatre of Mr and Mrs Krabat

My previous knowledge of Borowczyk was pretty limited. There was a review (extremely unfavourable) of Immoral Tales in Cinefantastique (1976, Volume 5, Number 2) in which David Bartholomew complained of the film’s joylessness, juvenile anticlericalism, and pedestrian style. Then there was the notoriety surrounding The Beast, Borowczyk’s retelling of Beauty and the Beast. The latter, until now, is the only one of his films I’d seen (Cult Epics’ limited edition 3-disk set from 2004 – #2058 of 10,000). I was more puzzled than anything by The Beast because I was expecting the work of an arty pornographer, something like a more polished Jean Rollin. On an initial viewing, The Beast was disappointing as an exercise in eroticism … and it turns out, according to many of the supplements in the Arrow set, that Borowczyk himself disliked being labeled an “erotic filmmaker”. Certainly, there is nudity and sex in his films, but these elements form part of a pattern of wider concerns, dealing with issues of power, social structure, politics and religion. Running through the films in the set is a thematic conflict between primal, animal elements of human nature and the flawed systems we devise to control, channel or outright suppress those energies.

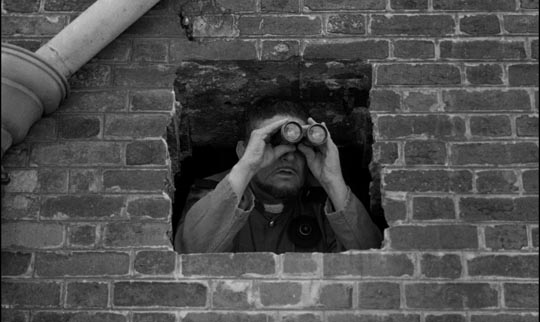

Borowczyk began as an animator, much of his early work consisting of hand-drawn images which belie their conceptual sophistication with a surface simplicity. His repertoire expanded with stop-motion and eventually live-action elements; in his animation there are affinities with Svankmajer and the Brothers Quay (though his earliest work precedes theirs). His live action features also have echoes – whether or not there was any cross-fertilization, Blanche and Immoral Tales reminded me of Pasolini’s Trilogy of Life, with a suggestion of what would soon come in Salo (the third episode in Tales, Erzsebet Bathory, has thematic and visual similarities to Pasolini’s grimly unpleasant masterpiece). The dissection of political power in the first live-action feature, Goto, Isle of Love, is reminiscent of Miklos Jancso’s early work (although Borowczyk’s camerawork is perhaps not as formally elaborate as Jancso’s, nonetheless his use of framing and movement expresses patterns of power which constrain the lives of his characters, who struggle against them in an attempt to exert their will as autonomous individuals), while The Beast is positively Bunuelian in its comic attack on a decadent and dying bourgeoisie, a corrupt social and religious culture collapsing under the disruptive influence of those sexual energies.

and lustrous natural worlds

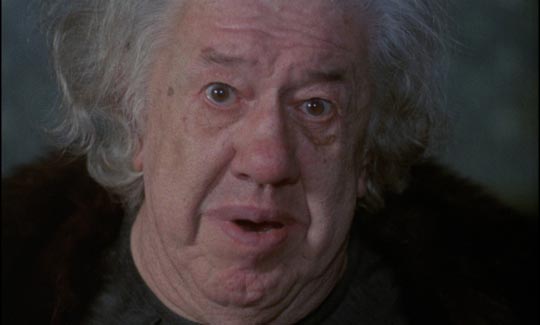

Briefly, Goto, Isle of Love is set on a small piece of land isolated from the world after an earthquake, a country which has developed a rigid, closed society; but the schemes of a prisoner/slave with designs on the ruler’s wife bring death and chaos. Blanche is an exquisite Medieval story of the blameless young wife of a grotesque, wealthy old man (the unique Michel Simon), who finds herself the object of not only her stepson’s desire, but that of the visiting king and his hedonistic page; although she remains faithful to her husband, he sees her as the guilty party and the stage ends up littered with bodies. Immoral Tales has four stories, moving backwards in time from the present to the 18th Century, all of which revolve around the manipulative and destructive potential of sexual desire. And The Beast, expanded from a discarded fifth section of Immoral Tales, is set in a chateau populated by the remnants of a degenerate aristocratic family who are determined to marry off their deformed son to an unsuspecting American heiress; the original short becomes a dream sequence woven into the narrative, both “explaining” the family’s degeneracy and privileging the power of female sexuality. (The shorts and Borowczyk’s first, animated feature, Theatre of Mr and Mrs Kabal, are too diverse and multi-layered to synopsize briefly here.)

and Paloma Picasso as Erzsebet Bathory

Interestingly, Borowczyk brought the sensibilities of an animator to his live-action work (a point made repeatedly by cameraman and collaborator Noel Very in his commentary on almost an hour of silent behind-the-scenes footage from the shooting of The Beast, in which we see the director minutely guiding the performances of his cast – apparently much to the annoyance of some of his distinguished actors); one of the most distinctive elements of his visual style is a deliberate lack of depth, an avoidance of perspective, which gives the films a two-dimensional graphic quality not unlike the proscenium effect of early silents, with actors carefully moved within the frame to create patterns rather than what we might more familiarly expect in terms of action. This controlled visual space makes Borowczyk’s unconventional editing techniques even more startling; rather than creating a sense of seamless movement, his approach is to create a continuous sense of disruption, of social stasis collapsing into chaos.

Far from being the clumsy filmmaker criticized by Bartholomew in that Cinefantastique review (he refers to Borowczyk’s “stolid editing style” and calls Immoral Tales “shamefully banal”), Borowczyk proves to be a stylist of great wit and visual precision whose work is dense with thematic layers and illuminated by dryly comic touches; his camerawork is original and expressive and his editing dynamic. The darkness which haunts these films doesn’t arise from a conservative attitude towards sexuality, but from a recognition of the damage wrought by all the social mechanisms which have been devised to suppress sexuality. The eroticism in his films doesn’t exist merely for its own sake, as a way to titillate an audience, but rather as a recognition of the importance of sexuality to all human experience.

All of this, of course, would be apparent from viewing the films in their widely available individual releases, but having them together in the set creates a larger context in which there is a degree of cross-fertilization which is greatly enhanced by the critical writing in the accompanying book. And as a bonus, the price I paid for the box was actually lower than the cumulative price of the separate releases (although now, already out of print, the going price from Amazon sellers is around £300).

Withnail and I (1987)

Sex turns up in the second of my recent limited edition purchases from Arrow, but in this case as a source of anxiety and misunderstanding. Bruce Robinson’s Withnail and I has been one of my favourite films since I first saw it in a theatre in 1987. And yet, as many times as I’ve seen it, I still find it hard to describe to anyone who hasn’t seen it. It sounds boring and depressing when reduced to a brief synopsis, yet is in the watching one of the funniest films I know, and a wonderful study of character. I tend to shorten my recommendation now to a simple “It’s the funniest movie ever made about alcoholism and depression.” If that doesn’t pique your interest, you probably won’t like it.

Bruce Robinson had a decade-long career as an actor which began with the role of Benvolio in Franco Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet (1968) and included, among various television parts, major and minor roles in films as diverse as Ken Russell’s The Music Lovers, Barney Platts-Mills’ Private Road, Roddy McDowell’s Tam Lin, peaking with the lead opposite Isabelle Adjani in Francois Truffaut’s The Story of Adele H. But he wasn’t really satisfied with that as a career and made a dramatic change by writing the Oscar-nominated and BAFTA-winning screenplay for Roland Joffe’s The Killing Fields. He followed that with a script based on his own experiences back at the beginning of his acting career, a blackly comic saga of a pair of would-be actors sharing a flat in Camden Town, waiting desperately for a break, sinking into drug- and booze-infused paranoia. That script is packed with hilarious, quotable lines, and yet it feels securely rooted in reality. These are living, breathing characters, a vision in which a terrifying fear of failure is staved off with a fragile shield of humour.

“I” (the Robinson character) struggles to maintain some degree of stability against the flamboyant storms inflicted by Withnail (based on Robinson’s 1970s roommate Vivian MacKerrell), a man whose fears and insecurity have turned him into a complete alcoholic. Hitting something like bottom, “I” suggests that they get away for a few days in the country – this awful holiday makes up the bulk of the film, a series of disasters and comic encounters which climax with the arrival of Withnail’s Uncle Monty (owner of the cottage) who, it turns out, has been told by Withnail that “I” will be sexually available to him. The anxiety this provokes might easily have descended into homophobic parody if not for the richly drawn and sympathetic treatment of Monty (the superb Richard Griffiths), becoming instead a great comedy of misunderstanding (based on Robinson’s own experiences as an insecure young actor hotly pursued by Zeffirelli during the shooting of Romeo and Juliet).

In fact, every character, no matter how small a presence in the film, is imbued with depth and nuance. Every scene, no matter how funny, is steeped in a sense of melancholy; even at the end when “I” finally gets that all-important call and has at last a way forward, this new possibility is overshadowed by a sense of loss; he’s leaving Withnail behind, and both know that this is going to be the end of their friendship. Withnail’s final drunken delivery of a soliloquy from Hamlet to an audience of zoo animals in the rain takes on the tragic air of ruined potential, a spectre of failure which the booze can no longer stave off. The great theme of Withnail and I is the fear – and cost – of growing up, of leaving behind careless freedom and assuming adult responsibilities. The sadness at the heart of the film comes from recognizing that that sense of childish freedom is illusory, that it can’t possibly be maintained indefinitely, and that growing up entails accepting and working within other parameters which at first glance seem far more constraining.

But what makes Withnail and I the treasure that it is was Robinson’s fortuitous discovery of Richard E. Grant. In his first film, Grant is a force of nature, giving a performance of such comic intensity that at first the despair underlying it might not be apparent. Withnail is larger than life and yet absolutely like the hopelessly self- destructive friend most of us have had at some time in our lives. Even supported by the rest of the great cast (Paul McGann as “I”, Richard Griffiths as Monty, Ralph Brown as drug dealer Danny, Michael Elphick as Jake the scary poacher …), the film would be doomed to caricature without the anchoring presence of Grant’s inspired madness.

The extras in Arrow’s edition include four featurettes made for Channel 4 in 1999 which deal with Robinson’s career, the making of the film and the passionate fan base it has developed over the years; two commentary tracks – the first with Robinson, who has a tendency to focus on everything he thinks he did wrong when making it, although he also provides a lot of interesting insight into his process; and the second with critic Kevin Jackson, who wrote the BFI Modern Classics monograph on the film. This latter is one of the all-time worst tracks I’ve ever come across and I’m not sure why Arrow bothered to include it; Jackson likes the film so much that he repeatedly makes a point of not talking over the wonderful dialogue, but rather just sitting there chuckling to himself, apparently unaware that anyone listening to the track will already have watched the movie and has come to him for some information about the production. I gave up after 15-20 minutes because it was so hopeless.

The useful extras give a fairly good account of the film’s production, with Robinson’s inexperience combined with the unusual tone leading Denis O’Brien at Handmade Films to try to shut the project down just days into the shoot. That combination of inexperience (bolstered by a talented cast and supportive crew) with the very personal nature of the script resulted in a film quite unlike any other; when it was released, it got a mixed reception and didn’t make a lot of money, but it attracted and held on to an enthusiastic and faithful audience. Which cannot be said of Robinson’s second feature, also included in the set.

I admit to being hugely disappointed by How to Get Ahead in Advertising, also starring Richard E. Grant, when I first saw it. Its satire of consumer culture seemed rather obvious and the whole thing played at such a sustained manic note that it got tiresome. And yet, seeing it again now in a fine new transfer on Blu-ray, watched immediately after Withnail and I, I felt inclined to be more generous towards it. In its way as idiosyncratic as its predecessor, it nonetheless lacks the earlier film’s nuance. It comes across like being cornered by an angry man intent on haranguing you about the failures of modern society, but it does nonetheless contain a lot of fine comic invention. Perhaps the difference is just that in Withnail Robinson was telling us about his personal life while in the follow-up he had an axe to grind; the result feels less organic.

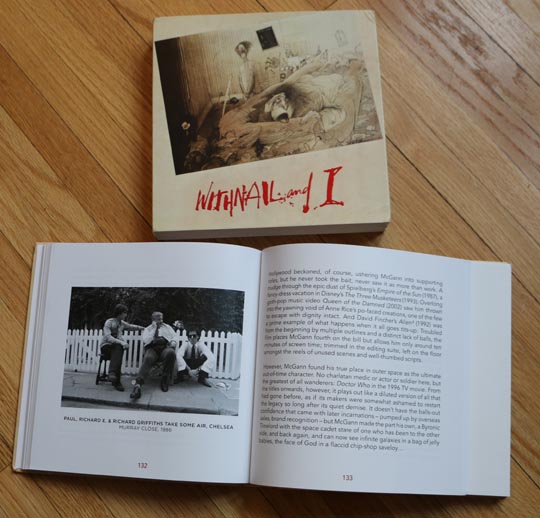

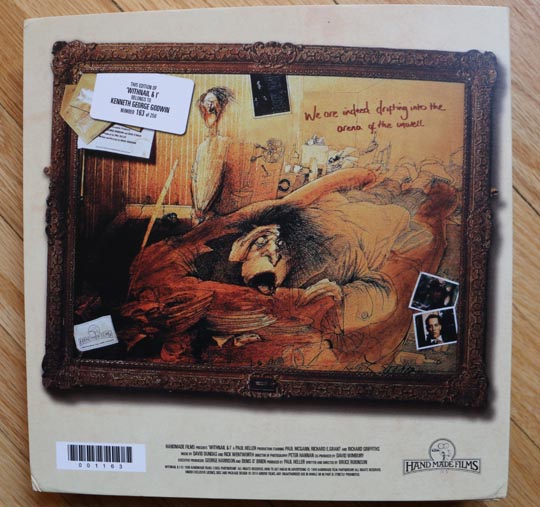

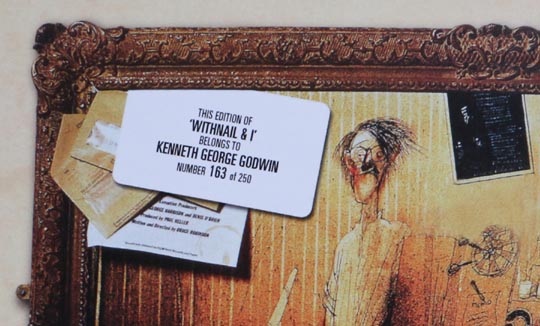

While the aim of Camera Obscura is obviously scholarly, the Withnail and I special edition is aimed squarely at fans. The 1000-unit limited edition, which comes inside a hardcover book with contributions from Robinson and various critics, along with excerpts from contemporary reviews of both films, illustrated with behind-the-scenes photographs, was offered with several options for personalizing your individual copy; there were four different designs for the slipcase (250 of each), with several quotes from the film to choose from (I decided on “We are indeed drifting into the arena of the unwell”); plus you got to have your name printed on the cover (“This edition of Withnail & I belongs to Kenneth George Godwin: Number 163 of 250”). The two films plus special features will be released in February on Blu-ray, but the collector (and fan-boy) in me couldn’t resist the more expensive package.

Comments

pathology

I’ll try to see Withnail and I.