Criterion Blu-ray review: The Sword of Doom (1966)

The Samurai film, like the western, is a versatile genre, affording scope for action, morality plays, comedy, and serious historical drama. By and large, samurai films are set during the period of the Tokugawa Shogunate (1603-1868), during which stability was established in Japan through a rigidly structured social order imposed by military government. The broad outlines of the period are familiar to fans of the genre: feudal lords supported by a warrior class (the samurai), beneath whom ordinary people – peasants, tradesmen – exist in a generally powerless state. Films which concentrate on the ruling class and samurai deal with issues of power and, most importantly, honour; films which look at the lower end of the social spectrum tend to be more critical, seeing the people as victims of an oppressive system which makes it very difficult for them to survive. These lower classes are also shown to be helpless in the face of conflicts between lords, treated with violent contempt by samurai.

For their latest release in this genre, the Criterion Collection have opted for what may be one of the most confusing, least accessible (to a western audience) samurai films: Kihachi Okamoto’s The Sword of Doom (1966). As Stephen Prince in his commentary track and Geoffrey O’Brien in his booklet essay point out, some of this film’s strangeness arises from the fact that it was based on a serialized novel by Kaizan Nakazato, begun in 1913 and left unfinished at his death in 1944. This popular work had given rise to a number of film adaptations before Okamoto made his idiosyncratic version in 1966 and a Japanese audience was likely to be familiar with the larger surrounding narrative (and the history it was rooted in), permitting the director and his screenwriter Shinobu Hashimoto to leave out large quantities of connecting tissue as they narrowed their focus to the character of Ryunosuke Tsukue (Tatsuya Nakadai).

The film is set during the final years of the Shogunate, as various factions fought to maintain the collapsing system while others strove to restore the Emperor. The political background is sketched in in ways which demand outside knowledge from the audience (Prince’s commentary is invaluable in helping to make sense of the film’s events), but Okamoto’s interest is in the psychological portrait of a killer who has become disconnected from any external motivations and becomes progressively unhinged as he pursues his deadly “art”. In this focus, as well as in Okamoto’s often radical technique, the film has a startlingly modern sensibility; in tone, The Sword of Doom is “samurai noir” and in subject it bears comparison to Imamura’s Vengeance is Mine as a depiction of sociopathology.

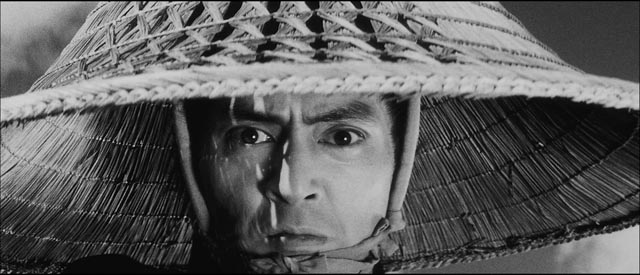

Okamoto was a versatile studio director, at home in a number of genres, but best-known for his samurai and war films. He was a master of action scenes, with his swordfights among the best ever committed to film. The opening scene of The Sword of Doom exhibits his skills to their best advantage: after a striking opening shot which aligns Ryunosuke’s straw hat with a distant mountain top, immediately giving him the air of a powerful natural force, we are introduced to Omatsu (Yoko Naito) and her grandfather (Kamatari Fujiwara), crossing the mountain pass on their way to Tokyo (in that opening shot, we can glimpse Omatsu approaching the mountain crest in the far distance beyond Ryunosuke’s hat, a tiny detail easily missed). As Omatsu goes to find water, her grandfather prays at a small shrine; this sequence is shot and edited in a quite radical way, each image carefully composed in widescreen to create a sense of graphic space in depth, circling around the grandfather as he prays for death to release Omatsu of the burden he feels himself to be. And at the moment he finishes praying, the grandfather moves slightly and Ryunosuke is revealed looming behind, like a mystical force which has arrived in answer to his prayer. But the sudden death he metes out is brutal and senseless. If Ryunosuke is an angel of death, he’s one devoid of empathy or any spiritual dimension at all.

What follows roughly parallels the stories of the killer and Omatsu. The girl is found and helped by a thief who places her with a woman who eventually turns out to be unconcerned for her welfare, selling her to a brothel, while Ryunosuke pursues his passion for killing, becoming involved with a faction fighting for the restoration of the Emperor … not through any political conviction, but rather because it provides a justification for the killing which for him, it becomes increasingly clear, is a form of sexual gratification. This character is a man whose extreme urges are given free rein because of the turbulent political situation and the film’s interest is in those urges, not the circumstances which unleash them. Omatsu’s story serves to personalize the consequences of Ryunosuke’s actions, and their paths finally cross again at the film’s climax.

The narrative such as it is is structured around three superlative fight sequences (with several smaller moments of violence in between); the first, occurring in mist-shrouded woods, is presented in a single wide tracking shot from slightly above, through which we see Ryunosuke cutting his way through a large number of men who have ambushed him to get revenge for his having just killed an opponent in a formal match. The relentless movement of character and camera further imbue the swordsman with the impression of a deadly natural force. The second battle, interestingly, has Ryunosuke standing aside as an observer as the gang to which he belongs attacks a palanquin which they believe is carrying an official, but which in fact carries the sword master Toranosuke Shimada (Toshiro Mifune in an authoritative supporting role); Ryunosuke watches Shimada slaughter the entire gang, as if observing himself from outside, and the sight has an almost catastrophic effect on him. The sexual pleasure he has previously exhibited in the wake of killing seems to have been replaced by a devastating uncertainty. In Nakadai’s remarkable performance we can see the insanity finally rising up to consume Ryunosuke.

In the final battle, we get the sense that we are now trapped inside the character’s own unhinged mind; as he seems to be plagued by ghosts, he begins to lash out, destroying the room he’s in as he slashes at shadows which are memories of his previous victims. His own gang, having realized that he is no longer in their control (not that he ever was) have come to kill him, and he cuts his way through a maze of rooms and corridors in a seemingly endless act of slaughter … in fact, it’s not “seemingly” as Okamoto freezes the image in mid action, trapping the completely insane Ryunosuke in what has become an eternal act of violence.

The Sword of Doom, for all that its context may seem ungraspable, is a precisely controlled film, a chilling dissection of murderous pathology fostered by a corrupt and unstable society which itself has been firmly rooted in the use of violence to maintain itself. Ryunosuke’s madness lies in his acting for his own personal gratification rather than serving the needs of political masters. Okamoto’s staging and editing combine the beauty of skillfully composed widescreen imagery with the radical disruptions of editing which is as idiosyncratic as anything seen in the French New Wave. A film obsessively focused on the formal qualities of swordfighting (and Ryunosuke’s unconventional style in particular), The Sword of Doom is itself a remarkable display of cinematic formalism, anchored by one of the most distinctive – and disturbing – performances found in the samurai genre. This may be the greatest performance of the versatile Tatsuya Nakadai’s career.

The disk

Criterion’s hi-def transfer from a fine grain 35mm print does justice to Hiroshi Murai’s beautiful photography. The night scenes are rich in detail and contrast, and the transfer maintains a film look which adds greatly to scenes like the fight in misty woods and the battle at night in the snow. The mono soundtrack is clear and full-bodied, giving real power to Masaru Sato’s score, from the distinctly noirish main title theme to the more epic elements supporting the action scenes; these ominous themes emphasize Ryunosuke’s psychological state rather than underscore the violence, for which Okamoto prefers to use richly layered natural sounds.

The sole supplement is Stephen Prince’s commentary, which as already mentioned is invaluable in providing context to the story and background of the production. This track doesn’t run through the entire film, jumping over several lengthy stretches, but what is there is detailed and pertinent.

Geoffrey O’Brien’s accompanying essay gives a good overview of the film’s relationship to its source material, and its position in Okamoto’s filmography.

Comments