Criterion Blu-ray review: Fellini Satyricon (1969)

Federico Fellini began his career – initially as a writer – in the final years of the Second World War, even contributing to the scripts of Roberto Rossellini’s seminal neo-realist Rome, Open City and Paisan. But when he began directing, it was obvious that temperamentally he was different from his neo-realist contemporaries. There was always a touch of the fabulist in Fellini, and an attraction to exaggerated forms of performance – vaudeville in his first feature, Variety Lights (1950, co-directed with Alberto Lattuada); the circus in La Strada (1954). Even a seemingly realistic film like The Nights of Cabiria (1957) has the air of a tragic fairytale. The presence of his wife, the waifish, almost ethereal Giulietta Massina, in many of his early films added to this impression, climaxing in Juliet of the Spirits (1965), his elaborate fantasia on marriage.

After Juliet, he spent several years struggling with projects which failed to materialize. This dry spell ended with the success of his wonderful short film Toby Dammit (1968, a segment of the Spirits of the Dead Poe anthology), following which Fellini broke with the contemporary world with his biggest and most fantastical film yet, an epic of ancient Rome called Fellini Satyricon (1969). In a sense this strange film freed the director from any need to maintain the pretense of realism and all the work which followed became fantastical and dreamlike – immediately after Satyricon, he made his documentary I clowns (1970), in which he addressed directly the importance of masquerade in his creative life; this he followed with his ode to his adopted city, Fellini’s Roma (1972); then came his autobiographical stream-of-consciousness memoir Amarcord (1973); then another highly theatrical historical film, Fellini’s Casanova (1976). Eventually the disconnection from reality led to diminishing returns with the visually sumptuous but narratively weak City of Women (1980) and And the Ship Sails On (1983) …

But that transitional point in 1968-69 remains one of his greatest achievements, visually unsurpassed in his work and conceptually more daring than anything else he made. Fellini Satyricon, an adaptation of the fragmentary remnants of a Roman novel attributed to Gaius Petronius Arbiter, a courtier in Nero’s Rome, is quite unlike any other movie. The timing of the production tempts an interpretation that the film is an allegory of the ’60s, a time of social breakdown and sexual abandon – and in broad terms this may be valid. Fellini Satyricon is indeed a depiction of society collapsing into decadence, no longer able to sustain itself as a stable entity, social bonds breaking as debauchery and violence become endemic. But Fellini brings something new to the historical epic.

In the long tradition of movies set in the ancient world, there has always been a tendency to make the characters accessible, imbued with personalities informed by modern ideas of psychology. Fellini does everything he can to strip that psychology from the characters, to observe them as if they were members of another species who can be known only through their actions. (“I am examining ancient Rome as if this were a documentary about the customs and habits of the Martians,” he said in an interview around the time of the film’s release.) This, and the film’s visual design – sets, costumes, cinematography – transform the ancient world into an alien planet, a science-fictional “other place” which has only the most tenuous connections with the world it has eventually evolved into. The result is one of the most lushly imagined fantasies ever committed to film.

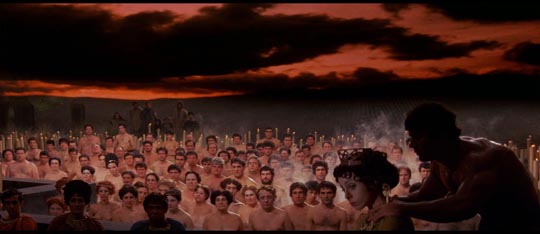

Fellini’s stated aim was to re-create the pre-Christian world, a time before the Church filled society with guilt and fear; the world of Satyricon is one of free-form sexuality – not free love in the hippie sense, which was a willful reaction against guilt and repression, but rather a polymorphously perverse, fluid expression of sexual energy. The film follows the adventures of friends Encolpius (Martin Potter) and Ascyltus (Hiram Keller), beginning with a falling-out over the slave Giton (Max Born), whom Encolpius loves and whom Ascyltus has just sold to the actor Vernacchio (Fanfulla). In a series of episodes – the film is deliberately disjointed, lacking a lot of narrative connective tissue (in emulation of the surviving fragments of the novel) – the two friends and occasional lovers witness the chaos of this collapsing society. The high points involve the literal collapse of a vast building during an earthquake; the appalling excesses of a banquet put on by Trimalchio (Mario Romagnoli), a former slave who has become a fabulously wealthy land-owner and successful poet (through plagiarism); the strangely beautiful and peaceful suicide of a patrician couple (Joseph Wheeler and Lucia Bosè), who prefer to die rather than await their fate at the hands of a new Emperor; capture by the slave trader Lica (Alain Cuny), who falls for Encolpius and marries him in an elaborate ship-board ceremony; and Encolpius’ encounter with a Minotaur and subsequent impotence, for which he seeks remedy with the witch Enotea (Donyale Luna).

The world of Satyricon is at once both harsh and beautiful, cruelly funny and casually violent. Death is often sudden and incidental to anyone’s intention, and when it occurs the characters merely move on to other concerns. This is a world in which passion is exhausted, and its inhabitants exert themselves strenuously at various physical pleasures in hope of reviving their spent desire. All transactions, emotional and physical as well as material, have been reduced to commerce; money has replaced art, poetry, even love. Here, perhaps, surfaces another parallel with the modern world: although there are hints that magic still exists, this ancient Rome has devolved to a purely material existence and the madness of these people lies in the absence of meaning, a vacuum which they try to fill with sensation. No wonder the film replaces narrative with spectacle.

The sets and costumes, designed by Danilo Donati and shot by Giuseppe Rotunno, give weight and colour to Fellini’s phantasmagoric imagination, providing the film with a physical grounding even as the characters remain enigmatic and unknowable. The film is full of Fellini’s fascination with the bizarre and grotesque, with freaks and outsiders and the weight of flesh itself. Against the decadence and moral decay, the only counterweight is the idea of poetry embodied in the character of Eumolpus (Salvo Randone) who appears several times as a kind of guide for Encolpius. His final gesture of mockery demands that his greedy heirs literally consume his flesh before they can inherit his possessions. Encolpius turns his back on the cannibal feast and heads off for new adventures, the film like the novel ending in mid-sentence.

The disk

Criterion’s Blu-ray features a truly spectacular 4K transfer from the original film negative, with eye-popping colours and rich layers of detail which reveal every aspect of sets and costumes and, perhaps most importantly, the physical features of Fellini’s carefully chosen cast. This is a film of endlessly fascinating surfaces and the disk’s image offers much to linger over and appreciate.

The original mono soundtrack gives the film an appropriate other-worldly ambiance, with the post-synced voices adding another layer of distance which, rather than being distracting, aids in the film’s project of making the ancient world as distant as possible from our own experience.

The supplements

Once again, Criterion has provided a strong selection of supplements to enhance the film, beginning with a “commentary” which is actually adapted from Eileen Lanouette Hughes’ account of the production, On the Set of “Fellini Satyricon”: A Behind-the-Scenes Diary (published in 1971); this provides a vivid account of the making of the film virtually scene-by-scene.

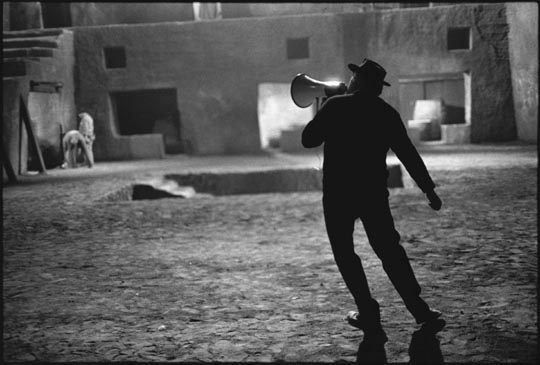

Adding colour and detail to this is Gideon Bachman’s 1970 behind-the-scenes documentary Ciao, Federico! (1:00:15), which combines interviews with the director about his philosophy and intentions with footage shot during several of the major sequences; for those used to seeing British and American directors at work, this all looks remarkably chaotic. With the absence of sync-sound recording, Fellini’s sets appear crowded and disorderly, with the director talking his actors through takes, giving them minutely detailed instructions about what they are doing – a technique which, combined with his disinterest in dissecting the characters and delving into psychology and motivation, adds greatly to the alienness of the world depicted in Satyricon.

Three brief interview clips – an audio piece recorded by Bachman (10:48), an excerpt from French Television (1:38), and a clip with Gene Shalit shot in a restaurant (2:08) – highlight Fellini’s playful sense of humour.

Fellini and Petronius (23:51) combines interviews with scholars Luca Canali (in Italian), who worked on the film as a consultant, and Joanna Paul (in English) about the work of Petronius and the relationship of the film to its source (Fellini used chunks of the original, but also added a great deal of material of his own invention).

Giuseppe Rotunno offers a brief account (7:38) of his working relationship with Fellini over eight films, starting with Toby Dammit; apparently he always had to intuit what Fellini wanted and come up with strategies himself to provide things which the director may not initially have known himself that he wanted.

There is also an interview with Mary Ellen Mark (12:57), a photographer assigned by Look magazine to document the production of Satyricon. She was provided almost unrestricted access to the production for a month and got some striking images of Fellini at work.

Finally, there’s a brief gallery of promotional materials, a rather battered trailer (2:24), and a booklet essay by film scholar Michael Wood.

Criterion’s excellent Blu-ray edition of Fellini Satyricon will hopefully establish this as one of the director’s most significant, and most fully-realized, features.

Comments