Twilight Time again …

My most recent acquisitions from Twilight Time are as eclectic as ever. A couple of mainstream Hollywood classics; an oddball excursion into pulp by one of the great Hollywood directors; and a devastating animated fable by a Japanese-American filmmaker based on a very English graphic novel.

Judgment at Nuremberg (Stanley Kramer, 1961)

Stanley Kramer was one of the most significant and influential figures in Hollywood from the late ’40s into the mid-’60s. Socially committed, he manifested a liberal worldview through the conservative and politically repressive ’50s. Defying the well-known dictum that “if you want to send a message use Western Union”, he foregrounded his liberal beliefs with great success until, interestingly, society began to catch up with the liberal surge following John Kennedy’s election, at which time Kramer began to be disdained as an unsubtle, preachy figure whose style was now seen as crass and obvious. It was at that crucial turning point – from Eisenhower’s conservative America to Kennedy’s supposedly youthful and forward-looking new America – that Kramer made his finest film, one which still stands as a powerful expression of moral commitment.

Judgment at Nuremberg was based on (and expanded from) a Playhouse 90 drama written by Abby Mann, one of the many successful writers from the golden age of live television drama. It ran against the political interests of the time, which preferred to avoid looking at the history of Nazism because Germany was now an ally against Russia in the Cold War. But that kind of thinking is just what the script is confronting, the idea that it’s better to ignore the moral wrongs of one’s own society in order to stand against those of an opposing nation.

There are a number of choices made by Mann which remain interesting even at this distance, the first among them being the decision not to focus on the famous first round of post-war trials in which the leaders of the Nazi regime were judged. In the play and subsequent film we see one of the later “minor” trials, ones which were conducted long after public interest had moved on to other matters. The judge, Dan Haywood (Spencer Tracy), has been given the job because no one else wanted it; an undistinguished jurist who’s never been placed in a position like this before, he is required to grow in stature as the trial progresses and the underlying legal and moral issues come into focus. Most crucially, this trial deals with German judges who remained on the bench and served the increasingly corrupt Nazi legal system. The film’s central question is at what point does someone decide that it’s wrong to serve an illegitimate system; most of the defendants adhere to a variation of the standard “we were just following orders” line; these were the laws of the nation and therefore had to be upheld even if they might have become distasteful.

The key defendant, Ernst Janning (Burt Lancaster), had been one of Germany’s principal and most astute legal minds in the years before Hitler’s rise, but as the Nazi regime took over and began transforming the country, Janning gradually bent his principles to accommodate the new system. He sits silently throughout the trial, refusing to cooperate with either the court or his own defence counsel, Hans Rolfe (Maximilian Schell); for the usually physically dynamic Lancaster, it’s an interestingly atypical performance – he manages to express the intense inner conflicts of Janning while sitting motionless until his climactic speech. Rolfe’s defence is that it was braver and more noble for his client to remain and do what he could to alleviate the worst depredations of the Nazis; the film’s final riposte, delivered with fierce authority by Tracy, is that any possible good was irrevocably undone the moment that the judge first sentenced to death a man he knew to be innocent. Expediency in the name of national good is a complete violation of the notion of justice (a point which also applied to what had occurred in the States during the McCarthy years).

Mann’s complex and nuanced text is embodied in generally superb performances by the large and distinguished cast, from established pros like Tracy, Richard Widmark (as the impassioned prosecutor), Lancaster and Marlene Dietrich to relative newcomer Schell (who had played the same role in the TV production) and even a young William Shatner as Judge Haywood’s aide. Even minor parts like the pair of German servants in the Judge’s assigned quarters illuminate the complex psychological implications of ordinary people living through the Nazi years, while Montgomery Clift and Judy Garland do some of their finest work in painfully raw scenes in which they testify on the stand to the judicial crimes committed against them by these same judges.

Kramer, never credited as much of a stylist, uses an often mobile and expressive camera to serve the actors and their text, giving the film an unforced intensity which belies the usual accusation of crude preachiness. Early in the trial he effectively gets around the problem of language (a trial conducted in English with German-speaking prisoners and defence) by having Schell speak German as judges and prosecution use headphones to listen to simultaneous translation; the camera quietly backs away and into the booth where we hear the translators transforming Schell’s speech into English; then it moves out again and Schell is now speaking English – the conceit is that from then on, we are listening to the translation (the characters continue to use their headphones), but without the technical clumsiness which actual translation would impose. It’s an elegant solution to a problem which stands outside the drama, and it avoids what would otherwise have been an annoying distraction caused by simply having the German characters speak English for our convenience.

After Nuremberg, Kramer’s career became more erratic, ironically just as the country was beginning to move in the liberal direction indicated by his work in the ’50s. (It was just two years after this that he made his bloated comedy epic It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.) His later films, particularly works like R.P.M., Oklahoma Crude, The Domino Principle and The Runner Stumbles, seemed simply irrelevant and in retrospect critical opinion quickly downgraded his earlier work … and yet, whatever their faults, The Defiant Ones, On the Beach, Inherit the Wind and Judgment at Nuremberg, not to mention many of the films he produced during the ’50s, remain a rebuke of the “hold your message, it’s just entertainment” attitude which has often been used to suppress social commitment among filmmakers in the commercial mainstream.

Birdman of Alcatraz (John Frankenheimer, 1962)

Perhaps the experience of making Judgment at Nuremberg gave Burt Lancaster a new perspective on acting because his follow-up the next year takes the stillness he found in the role of Janning and builds on it in the far more complex role of Robert Stroud in Birdman of Alcatraz, the second of five movies the actor made with director John Frankenheimer. (It was also one of three films Frankenheimer made in 1962: All Fall Down, which I’ve never seen, Birdman and The Manchurian Candidate – it’s impossible to imagine any filmmaker today pulling that off!) The key points of Stroud’s story are given in the film – a murderer sentenced to prison in 1909, later committing another murder in prison and getting the death sentence, which was commuted by President Wilson in response to pleas from Stroud’s mother; the film doesn’t shy away from the character’s psychological dysfunction (an unhealthy attachment to his mother, a deep-seated rage which expresses itself in violent outbursts), but it does argue for the possibility of transformation, even redemption. A project about which Lancaster was passionate (he campaigned for Stroud’s release), Birdman is an unabashedly liberal plea for prison reform and an end to capital punishment. But for the most part it remains a finely crafted, detailed and intense character study.

The central issues raised by the film remain relevant – the conflict between ideas of punishment and reformation (reading angry comments on IMDb about the film’s “whitewashing” of Stroud indicate that there’s still an intense desire in some quarters for unmitigated punishment, with rehabilitation some kind of unacceptable mollycoddling of people who are irredeemably evil); the film follows Stroud through five decades of incarceration, his anger and willfulness putting him at odds with prison authorities who see thoughtless obedience to the rules as the only valid sign of rehabilitation. Stroud insists on personal dignity and through force of will, bends the authorities to accommodate him. All of this is accomplished through the unexpected medium of an injured baby bird Stroud finds one day in the exercise yard. Taking it back to his cell he nurses it back to health. Finally finding something he can focus all his emotional energies on, over the years Stroud accumulates more birds and gradually educates himself (in school, he never got past the third grade) in the science of birds, experimenting and developing avian medicines, getting letters published in journals, and eventually spending years writing a definitive text on bird diseases.

At each step of the way, he has to push against the administration with his intensely possessive mother fighting on the outside, gaining him publicity and generating public pressure in his favour. All through this, his obsession with the birds gradually humanizes him, allowing him to develop relationships with guards and fellow prisoners based on something more positive than anger.

This long film sticks very close to Stroud; we experience the world and the prison system through his perspective and if it never offers a solution to the problems of criminality and imprisonment, it raises serious questions about the direction society has clung to with its punitive model of justice. The film argues for the possibility of redemption (aligning liberalism with New Testament morality against society’s Old Testament desire for retribution), but it nonetheless treats the opposition with respect and even sympathy, with the prison governors portrayed by Karl Malden and Hugh Marlowe as much bound by the system as the men behind bars. Thelma Ritter is chilling as Stroud’s mother, who turns on him when he establishes a relationship with fellow bird-lover Stella Johnson (Betty Field), and Neville Brand and Telly Savalas offer strong support as a guard and fellow prisoner respectively.

Like Lancaster’s performance, Frankenheimer’s direction is restrained, intense and closely focused on detail (all the business involving the birds is remarkable and must have involved much painstaking work to achieve), while Burnett Guffey’s black-and-white photography manages the singular achievement of evoking the claustrophobia of prison life while simultaneously creating an expansive sense of the larger psychological space Stroud creates for himself.

But having said that, in light of my recent complaints about The Imitation Game, I need to address the film’s apparent falsifications; Lancaster imbues the character with a dignity which, by the end, has become an almost saintly calm. The real Stroud, however, was a violent, possibly psychotic man. A pimp already in his teens, that first murder was of a bartender with whom he got into a dispute over a prostitute; having knocked him unconscious, Stroud took the man’s own gun and shot him. According to Paul Seydor and Julie Kirgo on what must be one of the most disputatious commentary tracks I’ve ever heard (Seydor criticizes the distortions, while Kirgo excuses them because the film is so well-made), Stroud remained a dangerous man throughout his decades in prison, spending 43 years in solitary (labeled a “predatory homosexual”, though one has to wonder how this was determined since he was kept away from the rest of the population all that time). The film makes Stroud far more sympathetic than he apparently was in order to make its points about the failings of the prison system – as The Imitation Game distorted the character of Alan Turing in order to make its points about homophobia. And yet, I find Birdman gripping and, like Kirgo, enjoy and admire it for the sheer beauty of its craft. Who knows, perhaps in a few decades, I’ll be able to ignore the manipulative distortions of The Imitation Game in the same way.

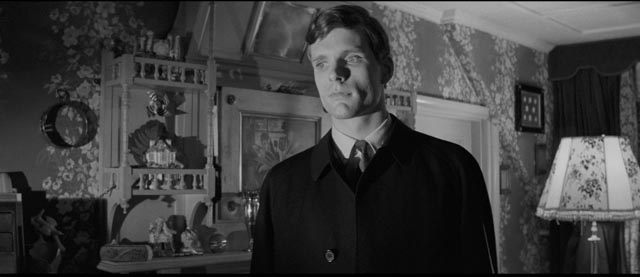

Bunny Lake Is Missing (Otto Preminger, 1965)

Otto Preminger’s contribution to the post-Psycho genre of twisted thrillers marks what seems to be the clear boundary between his prestigious heyday (a string of large-scale productions running from Anatomy of a Murder in 1959 to his Pearl Harbour epic In Harm’s Way in 1965, with Exodus, Advise and Consent and The Cardinal in between) and his generally reviled dotage: Hurry Sundown, Skidoo, Rosebud, etc. And yet there’s a lot to like, and even admire, about Bunny Lake Is Missing, beginning with its visual assurance. Preminger was a master of the camera, effortlessly controlling movement and framing to bring out the relationships among characters and between characters and their environment. Whatever their dramatic flaws, his films are almost always visually riveting.

With a script by husband-and-wife team John (Rumpole of the Bailey) and Penelope (The Pumpkin Eater) Mortimer – based on an Evelyn Piper novel set in New York – Bunny Lake centres on the increasing desperation of Ann Lake (Carol Lynley), a young single mother who has just moved from the States to London. On the first day of school, her young daughter Bunny vanishes and no one can even recall seeing her. The police, in the person of Superintendent Newhouse (Laurence Olivier), begin to doubt that Bunny even exists and Ann’s brother Steven (Keir Dullea, a couple of years before 2001: A Space Odyssey), through his aggressive intervention, seems to increase everyone’s doubts about Ann’s sanity.

Preminger doesn’t appear to be too concerned with the mystery itself – in fact, in retrospect, he tosses away the solution in the film’s first shot; then without fanfare reveals the truth halfway through as if he didn’t really expect anyone not to have figured it out already; he doesn’t even make much effort to exploit shooting on location in London as the Swinging Sixties kicked into full gear. His attention is instead focused on the film’s formal aspects – those wonderful camera moves, the evocative black-and-white photography – and his obvious pleasure in his actors’ performances. Lynley’s escalating hysteria could have been irritating, but Preminger has so much control of everything around her that instead it permeates the entire film to create the sense of a world with no stable grounding. It takes on a fairy tale atmosphere, made even more perverse by Noel Coward as her landlord – a man who reads poetry on the BBC, who creepily hits on Ann in her distress, and asks a policeman to flog him with a whip – and the inimitable Martita Hunt as Ada Ford, the founder of the Little People’s Garden school, who lives in an attic flat where she spends her days listening to tapes of children’s nightmares. Amongst the hysteria and perversion, the film is more or less grounded by Olivier’s policeman, one of his quietest, most restrained performances, and a reminder of why he was considered a great actor; with very little effort he holds the screen and single-handedly balances all the wilder elements.

In keeping with Preminger’s renowned boundary-pushing, the film makes no big deal about Ann’s status as an unwed mother and its later revelations of incestuous desire fit comfortably into the perverse atmosphere of the narrative. The weakest element is probably Dullea, but then he was handed a virtually impossible character to work with and, all things considered, acquits himself as well as any actor might.

As with some of Preminger’s more problematic films (Hurry Sundown, for instance, or Skidoo), there’s a pleasure to be found in Bunny Lake is Missing on the level of pure craft. It’s not the story he’s telling that matters here; it’s the way that he tells it and, fifty years later, there are still few directors who can match his filmmaking skill.

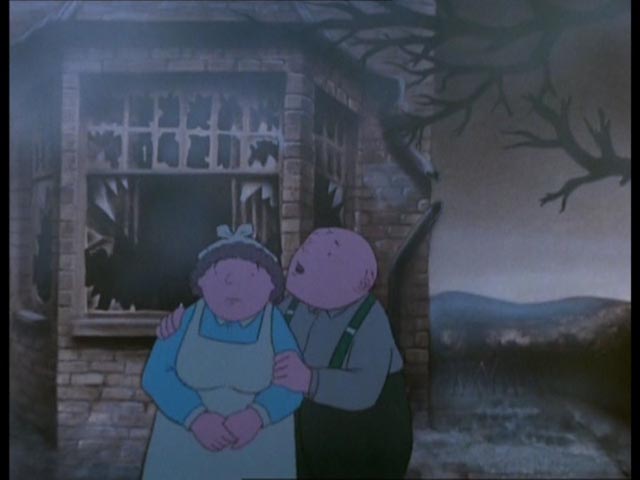

When the Wind Blows (Jimmy T. Murakami, 1986)

Jimmy T. Murakami, who died just last February at age 80, was an animator whose best-known film probably remains The Snowman (1982), still a perennial Christmas favourite. He made one live-action feature, the Roger Corman-produced Battle Beyond the Stars (1980), a cheap Star Wars knock-off with a John Sayles script loosely based on The Seven Samurai; it’s a minor movie, but nonetheless one of the more entertaining examples of its kind. Apart from an animated adaptation of A Christmas Carol (2001), he made only one other feature, but that one is a masterpiece. Based, like The Snowman, on a book by Raymond Briggs, When the Wind Blows is a devastating portrait of ordinary people caught up in the unimaginable horror of nuclear war.

This feature couldn’t be further from the delicate and charming fantasy of The Snowman. It deals with an ordinary English couple, Jim and Hilda Bloggs (voiced respectively by John Mills and Peggy Ashcroft) who live in a small house in the country and vaguely follow the news which warns of escalating international tensions and the possibility of war. Their main reference points are memories of surviving the Blitz during World War Two, complete with the familiar cliches about stiff upper lips and a cup of tea solving everything. Jim goes to the library and gets pamphlets put out by the government which offer civil defence advice – taping paper over windows to reduce the flash of atomic explosions; creating an “inner core” by leaning doors against an inside wall and stocking the “shelter” with blankets, canned food and water. Hilda complains as Jim makes a mess following these instructions, but he insists that they must do what the authorities tell them.

When the bombs fall, they’re completely unprepared psychologically; they have no understanding of radiation, can’t comprehend the consequences of society being irreparably smashed. And so they quickly forget the precautions outlined in the pamphlets and gradually succumb to the slow, unpleasant effects of fallout. As they gradually die this long, lingering death, they never lose their attitudes of trust and subservience to authority. These are the ordinary people at whom Peter Watkins aimed his savage polemic The War Game, the people whose complacency and lack of imagination make possible the appalling, dangerous power games of politicians.

The visual style of When the Wind Blows is strikingly imaginative with the simple, charmingly hand-drawn characters situated in a three-dimensional space created (pre-CGI) by manoeuvering a camera through miniature sets and then converting each frame into an animation cell to be combined with the drawn elements. The effect is to give the deceptively simple storybook narrative a grim grounding in reality; this balance between animation and reality gives the film enormous emotional power, the fate of the clueless couple becoming heartbreaking in a way which would be difficult to achieve in live-action – the distancing effect of animation makes it possible to continue watching a horror which would be unbearable in reality, and yet by allowing us to stay with it, its implications become unavoidable.

Twilight Time’s Blu-ray allows the film’s visual subtlety to come through strongly, and it’s enhanced with an engaged and informative commentary track with Assistant Editor Joe Fordham, moderated by Nick Redman, which makes clear how intensely committed director Jimmy Murakami was to the project. Murakami himself is present on the disk as the subject of Se Merry Doyle’s feature-length documentary Jimmy Murakami: Non-Alien (2010), which deals with his work as an artist and filmmaker, work deeply influenced by his experience as a Japanese-American who, as a young boy, was carted off with his family to a concentration camp in the California desert during the Second World War. This experience created a rupture which never healed, shattering his sense of being American and sending him into a life-long state of exile, with most of his filmmaking done in England, Ireland and parts of Europe.

Doyle’s documentary follows Murakami from his home in Ireland on a trip back to the States for a reunion of former detainees at the Tule Lake camp. There’s a bittersweet tone to the film as it becomes clear that the injustice and hardship he was subjected to as a child had a powerful influence on his development as a person and an artist. The distrust of authority in When the Wind Blows is informed by his experience of the camp and the attitudes engendered by that imprisonment towards the government which had destroyed his attachment to the country in which he was born.

Comments