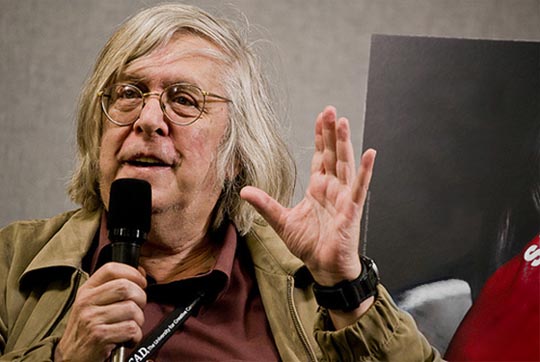

An evening with Jonathan Rosenbaum

If I was inclined to have heroes, I’d have to say that I met one of them this past week. Critic Jonathan Rosenbaum was in town for several events, one of which was an evening at the Cinematheque built around the column he writes for Cinema Scope: Global Discoveries on DVD. I missed the other two events (one at Plug In Institute of Contemporary Art on Monday, Cinema in the Age of the Internet: A Conversation with Jonathan Rosenbaum; the other at the University of Manitoba on Wednesday, a belated local “launch” for Criterion’s January release of Guy Maddin’s My Winnipeg on Blu-ray), but made a point of getting to the Cinematheque on Tuesday (not least because programmer Dave Barber had urgently requested use of one of my multi-region players for the event).

I first came across Rosenbaum’s work back in 1995 when I picked up a copy of his University of California-published Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism. I loved the writing, and appreciated his insights (even about films which I disagreed with him on). I quickly tracked down a copy of Moving Places, his earlier memoir about growing up with movies (his family owned theatres in Alabama); and have subsequently bought copies of every new book as it came out. And the first thing I read when each new issue of Cinema Scope comes out is his column, which has pointed me towards many interesting films which otherwise might have gone unnoticed.

The evening was relaxed and informal, with Rosenbaum introducing a collection of short films from very disparate sources (some of very rough bootleg-like quality), briefly talking about the films’ backgrounds and his reasons for showing them and answering questions from the audience. It was an eclectic package roughly held together by the idea of film as film criticism – that is, many of the films critiqued, or at least commented on, film form and filmmaking practice.

He started with lighter works and worked towards something darker and more complex, beginning with Charles Burnett’s 1995 short When It Rains, a lively, improvisational, jazz-inflected film financed by French television which becomes a portrait of community life in Watts, touching on selfishness, generosity and finally the fortuitous accidents which can abruptly alter relations between people – in this case for the better.

This was followed by two early short films by Abbas Kiarostami. The great Iranian director apparently holds them in low esteem and has never allowed them to be released commercially because he doesn’t consider that he was an artist when he made them. And yet there is definite art in their construction, though they were made as didactic educational films. The first, Two Solutions for One Problem (1975), is a charming and funny minimalist lesson in changing the ways in which children respond to situations: when one boy returns a borrowed book to his friend, the friend is offended to find that the volume has been torn. He retaliates by tearing one of his friend’s books in return and the conflict escalates through increasingly aggressive actions which finally end in a fistfight and black eyes. Here the four-minute film rewinds to the initial incident, with the boy pointing out the damage to the book to his friend; and the friend taking some glue to repair it. All is well and the friendship is preserved. The deadpan performances of the two boys and the simplicity of the staging give it, as Rosenbaum said, a Bressonian quality which adds to the humour underlying the message.

Orderly and Disorderly (1981) is longer and more complex. Juxtaposing two ways of behaving in order to illustrate the value of orderliness and consideration for others, we see what appears to be raw footage with the voices of director and cameraman on the soundtrack discussing the events in front of the camera. Kids leave a classroom and head down the school staircase, first in orderly lines, then in a rushing noisy crowd; they leave the school and go to a water fountain to get drinks, pushing and shoving in one take, lining up quietly in the next. The same with boarding a school bus; here in the disorderly shot, we hear the filmmakers becoming impatient with how long it’s taking as the camera runs on for several minutes. Finally, moving out into the wider world, the filmmakers try to depict a city intersection where traffic and pedestrians vie with each other. Here, the filmmakers’ control of events completely breaks down as it becomes impossible to stage an “orderly” scene as random pedestrians run out among the vehicles which in turn force their way past each other. But then something interesting happens; the filmmakers give up their attempt to control and simply observe the chaos in front of them and, strangely, that chaos assumes its own forms of order. Yes, the pedestrians and drivers continue to force their way amongst one another, but the seemingly formless movement becomes a complex dance in which everyone manages to keep moving without hindering anyone else. As Rosenbaum pointed out, this becomes a metaphor for the limitations of filmmakers in their attempt to impose structure on the world around them.

The next film was radically different, highly stylized, using complex visual techniques to evoke the forms of film noir while simultaneously resolving a multi-generational family history. Exterior Night (1994) was made by Mark Rappaport (Rock Hudson’s Home Movies, From the Journals of Jean Seberg) at a German studio, using an elaborate bluescreen technique to place his actors into appropriated black-and-white film footage of city streets at night, big, crowded, smoky nightclubs and rooms with venetian blinds. Steve (Johnny Mez) traces the life of his long-dead grandfather Biff (David Patrick Kelly), a private eye who, after being shot, turned to writing pulp mystery novels. Steve seeks clues to Biff’s life in those stories and the lurid covers of the paperbacks, becoming involved with a club singer played by Victoria Bastel, who also plays his mother as well as the possible femme fatale responsible for that shooting incident.

Exterior Night is visually inventive, and it was nice to see David Patrick Kelly, the great villain from Walter Hill’s The Warriors and Joseph Ruben’s Dreamscape, enjoying himself as Biff – but at 36 minutes, the film eventually feels too long, merely repeating the same visual and stylistic points over and over again. A sample from the opening of the film can be seen here.

The next film on Rosenbaum’s list was a sharper, more pointed piece of film-as-film-criticism: Why Don’t You Love Me? (1999) by Matthias Müller and Christoph Girardet (number 4 in a series titled Phoenix Tapes) is built with clips from various Hitchcock movies, edited together with wit and an escalating intensity, which highlights (exposes?) one of Hitch’s major obsessions: destructively dominating mothers and the concomitant emasculation of weak-willed men. Distilling many features into a rapid eight-and-a-half minute montage produces a slightly queasy impression of an unhealthy pathology, an effect only partially mitigated by the humour produced by some of the astute juxtapositions achieved by Müller and Girardet.

The Hollywood-centric conceptions of this and Rappaport’s films were strongly countered by Rosenbaum’s next choice, Amit Dutta’s Kramasha (To Be Continued), a 22-minute Indian experimental film from 2007. With lush imagery and dreamlike editing, Dutta evokes a sense of myth and history surrounding family and community; the film’s sense of “otherness” (from a Western point of view) is in some ways an answer to and repudiation of the kind of narratives produced by the mainstream Western film industry. Like the works of Paradjanov, which it reminded me of, it suggests a richer, less material view of life rooted in stories and traditions handed down through generations, connecting the present to the past in a vital, living way.

Otherness is both theme and subject in the final film of the evening, Forugh Farrokhzad’s The House Is Black (1963), the first significant Iranian film directed by a woman. This blend of poetry and documentary evokes complex responses from the viewer (certainly from me), with its unflinching images of a community of lepers living in northern Iran. The visual horrors of the disease are juxtaposed with quotations from the Quran, the Bible and Farrokhzad’s own poetry which convey both the humanity of these outcasts from society and the spiritual tools they use to give meaning to their own lives. Forming an unexpected bookend for the program, it reflected back on the sense of community found in Burnett’s When It Rains and established a sense of connection across cultures and periods, lending the whole program a unified theme of shared humanity … and confirming the potential of film to bridge superficially different cultures by illuminating our common experiences.

Comments