The cinema of Alain Robbe-Grillet

Thirty-five or so years ago, when I was at university, I read several novels by Alain Robbe-Grillet. To tell the truth, I can remember very little about them (other than The Erasers, his first published novel, I can’t even remember the other titles). Mostly I recall pages of minutely detailed descriptions of things like a slice of tomato. There was a certain fascination in the obsessive attention to material things, the denial of such traditional novelistic elements as character psychology, but that fascination was mixed with an undeniable tedium. No doubt I wasn’t equipped at the time to comprehend what he was doing. However, I’ve loved Alain Resnais’ Robbe-Grillet-scripted Last Year At Marienbad since the first time I saw it (around the same time I was reading those novels – in fact I probably read the books because of the film); that attention to physical surfaces and the unknowability of the inner life of human beings seemed much better suited to film than to fiction.

What I wasn’t aware of at the time was that Robbe-Grillet himself had become a filmmaker in the ’60s, had in fact already written and directed seven features by the time I read those books, with another three to come before his death in 2008. I’ve only just now got around to seeing some of these films, thanks to a six-film Blu-ray set from the BFI (these same films have also been released in North America by Kino/Redemption, but I opted for the region B set because it includes – along with excellent interviews with Robbe-Grillet conducted by critic Frederic Taddei, which are also on the Kino disks – commentary tracks by Tim Lucas, which are not available on the North American releases; not to mention, the BFI set was far cheaper than the individual Kino disks). I’m not entirely sure what I expected to find – perhaps overly intellectual, theoretical works, something heavy and pretentious. I certainly didn’t expect his films to be as entertaining as they’ve turned out to be.

As in his novels, the films of Robbe-Grillet all play with the possibilities (and limitations) of narrative, the ways in which we construct and tell stories in an attempt to make sense of the world and our experience. These films are non-linear, elliptical, suggestive, contradictory, ultimately demanding an active engagement in the viewer to make sense of them – a sense which is finally something the viewer invents from the materials offered, just as we construct the meanings in our own lives. If that sounds heavy and pretentious, that’s not the way it comes across in the actual viewing of the films, which are visually rich, loaded with dry humour and, at times, mysteriously evoked emotions. Robbe-Grillet himself asserted that there was no inherent meaning, that his work was conceived as a kind of game for the reader/viewer. He distrusted the idea of a fixed truth.

L’immortelle (The Immortal One, 1963)

L’immortelle (The Immortal One, 1963) is perhaps the closest in tone to Marienbad, though less formally rigorous. Filmed in Istanbul for financial reasons, it deals with a French teacher (Jacques Doniol-Valcroze) who meets an enigmatic woman (Françoise Brion) who shows him around the city (there’s a travelogue element to the film which provides striking views of Istanbul and its surroundings). This woman seems to be haunted by unspoken things in her past which repeatedly force a distance from the man even as he falls in love with her. The film seems to have a circular structure suggesting an endless reiteration of this experience of unrequited romance; it’s packed with narrative and visual echoes and repetitions (as in Marienbad) and leaves lingering questions – is this woman an illusion conjured from the exotic setting? Is she a ghost, a figure from an alternate plane? Is the man himself dead, trapped in an endlessly repeating memory of the events which led to his own demise? Answers don’t interest Robbe-Grillet and the viewer is free to piece the fragments together in whatever way he or she finds most satisfying.

Robbe-Grillet had a great eye for locations and an unconventional way of blocking and cutting scenes (which apparently caused a lot of conflict with his crew who insisted that many of his ideas “wouldn’t work”). At times the characters seem to be observing themselves from outside. Although it lacks the finesse of Resnais, the film exhibits a similar tableau style, figures posed in space with little sense of time.

Robbe-Grillet learned a great deal from the process of making L’immortelle, particularly the limitations of his initial approach to filmmaking, which was too rigid; he planned out every moment and manipulated his actors like puppets, dictating every look and gesture. When he made his second feature, three years later, he had loosened up considerably and incorporated random chance and accident into the process. This approach became increasingly pronounced in the following films, with scripts being little more than a series of ideas and sketched scenes around which director and performers would improvise. The process of storytelling became an integral part of shooting, with the films undergoing their final stages of writing through extended work in the editing room.

Trans-Europ-Express (1966)

Trans-Europ-Express (1966) is a far more playful film, with Robbe-Grillet using genre tropes to make it more accessible, while simultaneously deconstructing those same tropes to reveal the artificial nature of storytelling and the absurdity of trying to impose order on a chaotic reality. The film begins with Robbe-Grillet himself boarding a train in Paris with another man and a woman. Robbe-Grillet is Jean, a writer-director working on a new project; the other man is his producer (Paul Louyet); the woman, script-girl Lucette (Robbe-Grillet’s wife Catherine, who appears in all the films in the set). As they settle back for the trip to Antwerp, Jean begins to outline the story of a proposed crime thriller about a man being groomed as a drug courier. As he invents this narrative, it begins to play out on the train around them with Jean-Louis Trintignant as Elias, the man being tested by a sinister organization.

The absurdity of many of the story’s events is called into question by both Lucette and the producer, with Jean switching and changing, dropping threads, inventing new ones, glossing over implausible coincidences and contradictions. And through it all, Elias begins to take control of his own story regardless of his creator’s intentions. Jean’s story is a pulpy, absurd crime fantasy, with events piled on one another arbitrarily. Almost as if resisting the endless games being played with him (by both John and the criminals he’s working for), Elias concentrates on pursuing his own perverse pleasures – he likes violent sex and eventually kills a prostitute (this element of sexual violence features in most of Robbe-Grillet’s films, and indeed in a less fatal way in his life, as S&M was a key part of his fifty-year marriage to Catherine) – while the gang’s plans collapse and the police move in … but even as the film exposes the absurdity of its genre elements, the characters gain a kind of conviction which gives weight to their fates despite the obvious contrivances.

L’homme qui ment (The Man Who Lies, 1968)

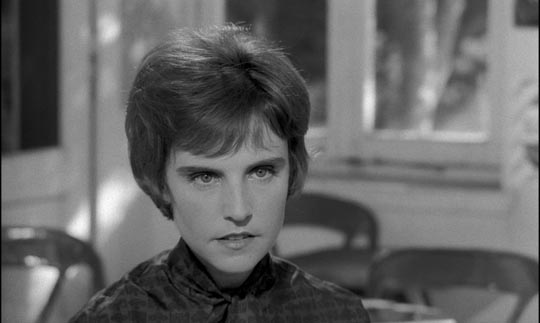

The idea of a narrative which repeatedly escapes the control of its creator becomes the central theme of Robbe-Grillet’s next film, L’homme qui ment (The Man Who Lies, 1968), the last to be shot in black-and-white. As the title suggests, the entire film is viewed through the eyes of a completely unreliable narrator, the man who calls himself variously Jan Robin, Boris Varissa and the Ukrainian (Jean-Louis Trintignant again). We first encounter this man running through a forest, apparently being pursued by German soldiers. But there is no attempt to create a plausible verisimilitude: the soldiers seem to have slapped-together uniforms and the man is wearing a modern suit and tie. We never see him in the same frame as his supposed pursuers, and yet at one point they seem to gun him down – the first of his several “deaths” in the film.

Intercut with this chase, we see three women playing a game of blind-man’s-bluff in what appears to be a run-down old castle. Eventually, the man arrives here and begins to insinuate himself into their lives. One of the women is Jan Robin’s wife Laura (Zuzana Kocúriková), another his sister Sylvie (Sylvie Turbová) and the third their maid Maria (Sylvie Bréal). The man, starting with Maria, seduces his way up the ladder towards Laura, intent apparently on taking the place of Jan Robin, a resistance fighter who has not returned from the war. In fact, at times he claims to be Robin although no one in the town recognizes him. Repeatedly, what he tells us is contradicted by what we are shown. He keeps changing his story, making himself the hero of a constantly shifting narrative.

Throughout the film, Robbe-Grillet interrogates the familiar tropes of the Resistance narrative, casting doubt on claims of heroism and the motives of those who make those claims. At the same time he continues to move further from the idea of character as a coherent psychological construct; motive and meaning become more and more contingent, something to be invented by the viewer in an attempt to make sense of these arbitrary events.

L’éden et après (Eden and After, 1970)

With L’éden et après (Eden and After, 1970) there’s a radical shift in Robbe-Grillet’s work, rooted in the move from black-and-white to colour. The formal qualities of this film supplant even those mocking concessions to narrative which shaped the earlier films. Built on improvisations around a set of themes, the meanings of Eden are rooted in the uses of colour and echoing images. It begins (unlike any of the previous films) on an elaborate studio set designed to evoke the geometric qualities of certain modern artists (Mondrian and Klee were a major influence), an implausible cafe in which students spend their time acting out fantasies of sex, violence and sexual violence. Through these games, one figure in particular, Violette (Catherine Jourdan), emerges as a focus point (this is what happened during the shoot, Robbe-Grillet’s fascination with the actress coming to dictate the direction of the film). With the arrival of an older man, Duchemin (Pierre Zimmer), an intruder into the students’ world, the games expand out into a wider world of opaque events and motives, which lead to both death and sexual awakening.

The mirroring of events propels the film in its second half to North Africa, with open spaces and sunlight replacing the artificiality of the first half’s interiors. There are elements of quest, of criminal activities, intimations of murder, kidnapping … all ultimately governed by Violette’s sexuality. Robbe-Grillet was frequently attacked as a misogynist and pornographer, but the writer-director’s personal obsessions seem to align in this and his subsequent feature with female power. His work is full of fetishistic imagery, but rather than an exploitative or reductive attitude, there seems to be a recognition of the complexity of sexuality and a fascination (as a man) with the expression of female desire.

Glissements progressifs du plaisir (Successive Slidings of Pleasure, 1974)

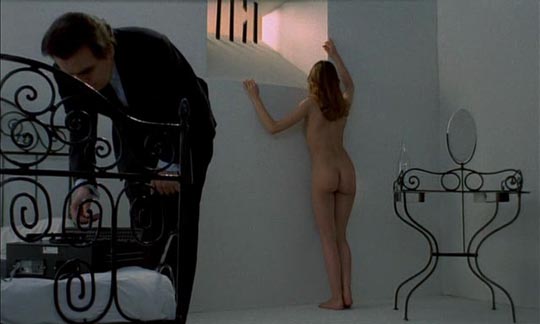

This becomes central to Glissements progressifs du plaisir (Successive Slidings of Pleasure, 1974). In many ways this is at the same time the most complex and yet accessible of the films in the set. At least its structure and symbolism seem easier to grasp on an initial viewing. This was also the film most openly condemned as “pornographic”, and indeed it does bear affinities to one of the most disreputable genres of the period: nunsploitation. There are also elements of the giallo; the narrative begins with the death of Nora (Olga Georges-Picot), the lover and roommate of Alice (no doubt a deliberate allusion to Lewis Carroll). Was this death the result of the S&M bondage games the two women were playing or, as Alice (Anicée Alvina) asserts, the work of a mysterious stranger who invaded their space.

Alice is placed in custody in an institution run by nuns, where the various figures of social authority run aground on the power of her uninhibited sexuality. There is initially the Detective who “discovers” the crime (an uncredited Trintignant giving a brief but hilarious performance); then the Judge investigating the case (the superb Michel Lonsdale mocking his own image as the dogged investigator in the previous year’s Day of the Jackal); and finally the Priest (Jean Martin). All these figures hopelessly try to contain Alice’s sexuality and end up ruined by its power. All of this activity serves as a critique of historical attempts to contain that power, particularly the witch hunts of the late Middle Ages and Early Modern period. These men and the institutions they represent are powerless before Robbe-Grillet’s pleasure in observing Anicée Alvina’s completely unselfconscious (and frequently naked) performance. The sexual power she expresses is irrepressible, uncontainable and ultimately a joyful refutation of the cramped energies of the patriarchal system.

*

The sixth film in the set, and the least effective (for me anyway) is N. a pris les dés… (N. Took the Dice, 1971), a made for television reworking of much of the material shot for Eden and After. Although an interesting illustration of the different uses to which the same material can be put, it doesn’t hold up as an independent work (though perhaps my opinion would have been different if I had seen it by itself without having seen Eden beforehand). Of all the films in the set, this seems most like an intellectual exercise rather than an expansive artistic creation.

All the films in the BFI set look fantastic – the richness of the first three films’ black-and-white well complemented by the eye-popping colours of the subsequent three. After that initial overly controlled misstep in L’immortelle, Robbe-Grillet proved to be an excellent director of actors, eliciting intense and playful performances from his casts which contribute greatly to both the thematic and entertainment values of the films. Although these six films had four different cinematographers, there’s a powerful and consistent visual sense running through them which must be attributed to a large degree to Robbe-Grillet himself. On the other hand, the essential complexity of the films’ editing strategies must be attributed to the long-running collaboration between Robbe-Grillet and editor Bob Wade (who also appears in bit parts in many of the films, including as the grave-digger in Successive Slidings who gradually uncovers each of the key objects which figure in the narrative as if deconstructing the patterns he has created as the film’s editor).

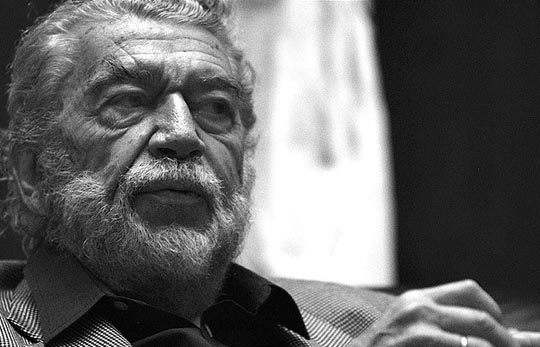

Each of the films (except for N. a pris les dés…) is accompanied by a half-hour interview conducted by critic Frédéric Taddeï with the writer-director the year before his death in 2008 at age 85. Robbe-Grillet comes across as lively, charming and erudite; he looks back on his work with a clear eye to both his achievements and his limitations, unselfconsciously open about his personal fantasies and fetishes and how they shaped his work. What comes through most clearly is the humour which he applied to his literary and cinematic games and the respect he had for his readers and viewers and their ability to take part in those games as active participants in the creation of meaning.

Four of the films have brief introductions filmed in 2013 by Catherine Robbe-Grillet who offers anecdotes about their making.

The final extra, and a substantial one, is the Tim Lucas commentaries on the five major films. Lucas is a passionate Robbe-Grillet enthusiast who has obviously pored over the films with unflagging attention. While I enjoyed watching all the films, I obviously missed an awful lot in terms both of what was going on in the films and of the many literary, historical and artistic references woven through them. The fact that I found them all so engaging even without the benefit of catching all these other levels of meaning is an indication of just how good a filmmaker Robbe-Grillet was. I look forward to seeing the rest of his work.

Like Arrow’s recent Walerian Borowczyk set, this BFI release is an invaluable introduction to a major film artist, too little known, who produced a significant body of work outside the mainstream.

Comments