Blaxploitation and historical counter-narrative

More by accident than design, my reading and viewing recently coincided in an interesting way. While browsing at a local bookstore, I came across a slim paperback called The Devil Finds Work. This essay (what might be termed personal film criticism – that is, it’s more about the writer’s own relationship to the movies than it is an “objective” critical assessment of individual films) was originally published in 1976 and, perhaps I should be embarrassed to admit, is the first thing I’ve ever read by James Baldwin.

Although barely more than a hundred pages, Baldwin’s examination of the way Black people have been used and abused in American film (and popular culture) probably gave me more understanding than anything I’ve previously encountered of the endlessly contentious arguments about race which have been a major element of American social and political discourse for the past two centuries, and which have flared up increasingly in the past decade. In particular, in addressing issues deeply rooted in the still unresolved legacy of slavery, Baldwin is very good at dissecting the ways in which white guilt has been projected onto the Black population. This contorted psychological process transforms real victims of American history – the African-Americans kidnapped, bought and sold, and relentlessly dehumanized – into a fantasized monstrous threat to white society. Given that Blacks have been oppressed and brutalized in America for three centuries, it seems telling that white society perceives itself as under threat from a dangerous Black other. (The history of the treatment of Native Americans and their depiction in popular culture reflects a similar distortion of reality into a myth useful to the dominant culture.)

The horrors of slavery, segregation, a legal culture which has been used so one-sidedly to oppress Blacks … all of this has been justified as a defence of white privilege against a mythic Black power which must be contained. White society has purposefully instilled fear in the Black community, and continues to do so. The recent outcry and protests against police shootings of unarmed African-Americans is a public reaction against these institutionalized mechanisms; in terms of social structure (whether deliberately or not), these shootings serve a similar function to the lynchings which were so commonplace in the 19th and early 20th centuries, a constant reminder of Black powerlessness and the enforcement of a subservient social position.

The corollary of this built-in fear and antagonism has been, in popular culture, an on-going attempt to defuse the image of a Black threat to white privilege. Baldwin is very good at deconstructing the “positive” images (replacing earlier gross racial stereotypes) of African-Americans promulgated by liberal Hollywood during the ’50s and ’60s. In such highly-praised movies as The Defiant Ones, In the Heat of the Night, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, the underlying purpose, rather than the empowerment of Blacks, is to reassure white audiences that they really have nothing to fear. The alternative to Black menace is shown to be a kind of Black harmlessness which lacks the power to endanger white privilege. In these films, the encounter with the Black character leaves the existing social order largely intact, but now with the advantage of knowing that Blacks aren’t really intending to take anything away from “us”.

It was in reaction to this agenda that outliers like Melvin Van Peebles and Bill Gunn strove to make films from a Black perspective. Van Peebles’ Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971) and Gunn’s Ganja and Hess (1973) were to some degree baffling to contemporary audiences (and critics) because their point of view was so unfamiliar. By mainstream standards, Sweetback was a crude, and crudely violent, piece of trash … but it nonetheless attracted attention because it proved to be a hit with “urban” audiences. If it perhaps seemed politically threatening, that fact was outweighed by commercial considerations and Van Peebles’ movie (unlike, say, Gordon Parks’ semi-autobiographical account of Black family life, The Learning Tree [1969]) became one of the prime inspirations for the flood of “blaxploitation” movies which hit theatres in the early and mid-’70s.

But in that new-born genre, Van Peebles’ anger was co-opted and paradoxically transformed into a conservative reinforcement of myths of Black criminality – although heroes and heroines like Shaft and Coffy and Foxy Brown are cast as tough, righteous crime-fighters, the overall context of these movies is a community chronically plagued by crime and violence, a view of the African-American community long held by the dominant culture. If many within that community ended up embracing this view as a gesture of defiance, it was still a kind of self-definition imposed by the oppressors.

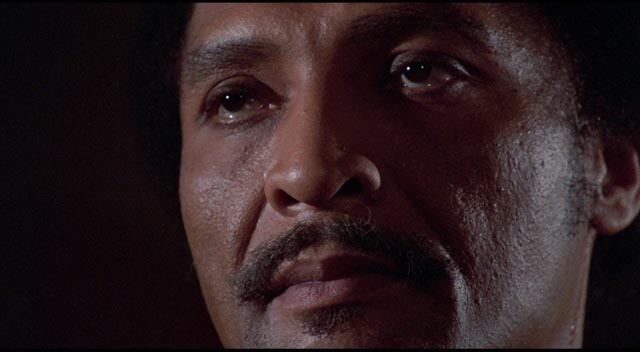

Which brings me to the odd coincidence I mentioned above. When I picked up Baldwin’s book, I had an order on the way from an Amazon seller, which arrived just a few days later. It was Shout! Factory’s new Blu-ray double-feature of Blacula (1972) and Scream Blacula Scream (1973), a pair of high-profile (low-budget) blaxploitation movies from the early ’70s. Like many of these movies, they are cheap, crudely written, and directed without much finesse (the sequel is actually better in this respect than the original). And yet, despite the stereotypes (including, in Blacula, embarrassingly broad gay characters), there turns out to be something interesting and unexpected in these two movies: the character of Blacula himself as played by the majestic William Marshall, who surely should have had the kind of movie career enjoyed by his contemporary, James Earl Jones. And yet Marshall somehow never got much above television guest spots (he’s probably best known as the King of Cartoons from Pee-Wee’s Playhouse, taking over from Gilbert Lewis in season 2). (He did however have a successful theatre and teaching career.)

In his commentary track on Blacula, blaxploitation expert David F. Walker (director of the documentary Macked, Hammered, Slaughtered and Shafted [2004]) offers a wealth of insight into the impact of blaxploitation films on an impressionable Black kid. He also points out that Marshall insisted on a major change – or rather addition – to the trashy script by Joan Torres and Raymond Koenig (this and the sequel are their sole movie credits): the entire pre-credit prologue was Marshall’s idea. In this sequence, we’re introduced to Prince Mamuwalde (Marshall) and his wife Luva (Vonetta McGee) as they dine with Count Dracula, a 17th Century European nobleman whom Mamuwalde is trying to recruit into his campaign against the slave trade. Mamuwalde is an articulate, learned, dignified man who unexpectedly finds himself and his wife the recipients of Dracula’s crude, racist contempt. Had American pop culture previously offered anything like this image of African culture and dignity? It’s a radical image and not surprisingly the Count, a stand-in for white European society and its colonial branch in North America, refuses to grant it any respect. He makes crude sexual advances on Luva in a direct attempt to humiliate Mamuwalde, then bites the prince on the neck; but he has no interest in recruiting the African into the vampire brotherhood. Instead, he seals him in a coffin where he will suffer an eternal, unquenched thirst for blood, a savage punishment for daring to assume that he was Dracula’s social equal. Luva is sealed into the tomb with him, doomed to starve to death.

When the coffin is bought three centuries later by a pair of gay antique dealers and taken back to Los Angeles, the nobility of the character is retained despite the curse which requires him to kill for blood. Instead of a cardboard blood-sucker turned loose in a modern city, Marshall (rising far above the material) gives us a tragic portrait of a man (and a race) forced into a position completely against his nature by a contemptible culture convinced of its own superiority. All too clearly, that culture is entirely devoid of its victim’s nobility. The story follows the now familiar line which has the vampire finding a woman, Tina (McGee again), whom he believes to be the reincarnation of his lost love (is this in fact the first instance of a now-standard Dracula trope which is definitely not present in Bram Stoker’s novel, but seems to be repeated in every new movie about the Count?). But having found her again, Mamuwalde will lose her not once, but twice more: after she’s shot by a policeman, Blacula saves her by turning her into a vampire; but then she gets staked by the film’s “hero”, Dr. Gordon Thomas (Thalmus Rasulala). Unable to take all this emotional pain, the vampire walks out into the dawn and lets the sun burn him to death, a bitter refutation of a world which will not acknowledge his right to exist.

The film’s implicit theme, which points towards the idea that if Blacks are violent it’s because white oppression has left them no choice, is not developed by the movie’s script; it’s something imposed through force of will by William Marshall himself, a remarkable actor whose commanding presence unbalances everything else in the film. It’s by no means certain that director William Crain, whose first feature this was (and whose subsequent career is spotty at best, and consists mostly of television work), was even aware of what Marshall was doing. In terms of the film’s structure, Dr. Thomas remains the hero and Blacula is positioned as a monster and villain, but as viewers we can’t help but side with the princely bloodsucker.

The sequel, Scream Blacula Scream, is in most senses a better film. The script is livelier, with its conflation of vampire lore and voodoo (Blacula is resurrected via a ceremony involving a pile of his bones and a sacrificial chicken), and the prince becomes involved with a powerful voodoo priestess played by Pam Grier. Director Bob Kelljan, fresh off Count Yorga, Vampire (1970) and The Return of Count Yorga (1971), adds some visual flair and gives the movie a narrative coherence largely lacking in the original. But, paradoxically, these improvements diminish Mamuwalde to some degree. Although Marshall remains an imposing presence, here he no longer has the powerful metaphorical role which makes the first film so interesting. It’s as if improvements in the movie’s conventional aspects serve to contain the actor (and character) in ways the clumsiness of the first film had been unable to.

In a way, these two cheap exploitation movies reiterate the process by which Black anger and expression have so often been diverted and defused into paths which seem less threatening to a white audience. Baldwin had contempt for what the popular culture was doing to Black experience at the time he was writing (including the cycle of blaxploitation movies), but William Marshall in Blacula gives a glimpse of something, some possibility, which pointed towards an alternative narrative (not too far different from what Bill Gunn achieved in Ganja and Hess, another film with an articulate, cultured Black vampire who defied stereotypes). Ironically, this cheap, crude exploitation movie indicated a very different path from the one followed by respectable, liberal movies like In the Heat of the Night and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, which did their best to assure us (the white audience) that there was nothing to fear. In contrast to the blaxploitation action movies and thrillers which were full of Black menace, Blacula through the character of Prince Mamuwalde suggested that we (the white audience) should maybe take on a sense of responsibility for those centuries of painful history, and the sometimes violent consequences arising from oppression, rather than just clinging to our privilege while cowering in fear.

Comments