Criterion Blu-ray review: Carol Reed’s Odd Man Out (1947)

The career of the British director Carol Reed poses an interesting question: how is it that in a long career, a filmmaker can make, in rapid succession, three masterpieces, while the rest of his filmography comprises competent if undistinguished films and the occasional more interesting but deeply flawed work? Reed, roughly a contemporary of both Michael Powell and David Lean, was for that brief postwar period (1947-49) considered by many critics to be the world’s greatest director, but unlike his two compatriots, he failed to sustain the success of those three films.

Like Powell, Reed learned his craft while making quota quickies in the ’30s. He was praised by Graham Greene during that period as one of the most accomplished British filmmakers who, Greene said, would obviously come into his own once he had the right material. His breakthrough came in 1940 with an adaptation of A.J. Cronin’s middle-brow left-leaning novel The Stars Look Down, about life in a Welsh mining community. Reed himself claimed that politics didn’t interest him and the film was somewhat scrubbed of Cronin’s political agenda – improvement of miners’ lives through nationalization of the industry – and was criticized for its negative portrayal of unions. However, its grim depiction of working life (in powerful contrast to John Ford’s sentimentalized version in How Green Was My Valley [1941]), and in particular its downbeat ending, marked Reed’s shift from light entertainment to serious filmmaking. Yet, that same year, he also made Night Train to Munich, the semi-sequel to Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes, which mostly showed that Reed was ill-suited to that genre; the uneasy mix of romantic comedy and Nazi horrors never finds a satisfactory tone.

Although the features made in the next few years (Kipps, The Young Mr. Pitt) are undistinguished, Reed did direct some notable propaganda films for the war department. But it was immediately after the war that he met with his greatest successes. A number of critics have asserted that Reed was only as good as his collaborators and it seems undeniable that the three postwar masterpieces were built on the best scripts he ever had to work with and, just as importantly, he worked on them with two of the finest cinematographers available: Robert Krasker on Odd Man Out (1947) and The Third Man (1949) and George Perinal, who had worked with both Rene Clair and Jean Cocteau in the ’30s, on The Fallen Idol (1948). Two of these films were written by Graham Greene (ironically, given his comments ten years earlier about Reed’s need for “the right script”), and Greene’s darkly ironic view of moral issues and guilt suffuses even the film he didn’t write, indicating a genuine affinity between the writer and director. But the marked stylistic differences between the two films shot by Krasker and the one shot by Perinal further complicate the question of Reed’s talent. Both Odd Man Out and The Third Man are famous for their aggressively expressionist camerawork, the heightened use of light and shadow, skewed camera angles and at times consciously poetic effects; while The Fallen Idol has a much lighter, more delicate touch.

Where then is Reed’s directorial identity located? Born into a theatrical family, he began his career as an actor himself and throughout his work there is an obvious sensitivity to performance (even as, in some cases, those performances have occasionally been criticized as overly theatrical). In his best work, there is a strong narrative sense allied with psychological acuity; in some of his less successful films, lacking the visual flair of the masterpieces, this attention to character is still evident even when the scripts are less well-crafted (perhaps most notable among these is the flawed, yet seriously underrated, Outcast of the Islands [1951]). What seems clear is that Reed, rather than shaping each work to fit a larger artistic intention, instead adapted his approach and style to the needs of whatever material he took on: a powerful talent, but not, in the accepted sense, an auteur.

Odd Man Out (1947)

Odd Man Out, Reed’s first postwar feature, deserves to be better known – and hopefully the Criterion Collection’s beautifully restored Blu-ray edition will help to place it on a par in viewer consciousness with The Third Man. Based on a novel by F.L. Green, the film depicts the final hours of an IRA gunman who is wounded during the robbery of a factory in an unnamed Northern Ireland city. The novel apparently is decidedly pro-Loyalist, but the adaptation (co-written by Green with R.C. Sherriff) transforms the protagonist, Johnny McQueen (James Mason), from a vicious terrorist into a tragically flawed man. In fact, the film is structured as a classical tragedy, initiated by a fatal error on McQueen’s part and inexorably following the consequences of his actions to a predetermined, deeply fatalistic ending. The location remains unnamed, as does the secret group McQueen represents (spoken of only as “the Organization”). The film is not specifically about the on-going political situation in Northern Ireland; rather, it’s a morality play about the ways in which McQueen’s situation influences everyone around him. Although there are no outright villains, there is selfishness, greed, and moral failing. Even the policeman on McQueen’s trail is treated with some sympathy – Odd Man Out is perhaps one film which genuinely illustrates Jean Renoir’s famous assertion that “everyone has his reasons”, and Reed is unwilling to pass judgment on anyone.

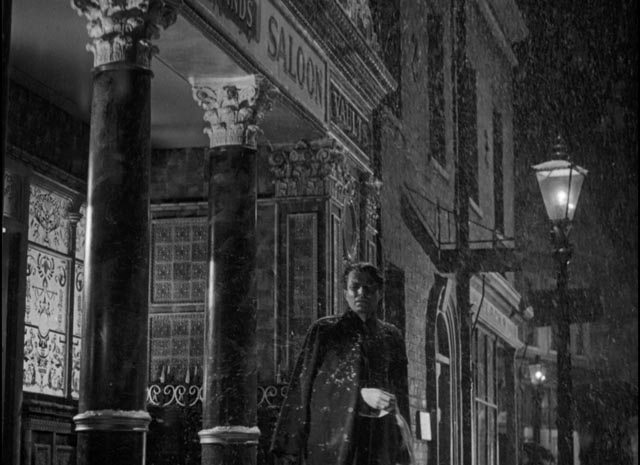

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the film is the way Reed reflects McQueen’s descent into delirium and despair through an evolving stylistic transformation which moves from the documentary-like realism of the early daytime scenes, in which McQueen and his co-conspirators plan and execute the robbery, to a more heightened and eventually expressionistically subjective depiction of McQueen’s feverish journey through a night which seems to embody the passage of the seasons as he slips inexorably towards death. Reed and Krasker go all out to infuse the narrative with visual meaning, to the point of displaying McQueen’s hallucinations through techniques reminiscent of silent cinema. Nothing in Reed’s previous work indicated a capacity for this kind of visual richness, the ability to go beyond the literary qualities of the script to a more purely cinematic embodiment of meaning. It’s as if the experience of the war had brought into focus for Reed the terrible things people were capable of doing to one another, but this awareness is combined with a deep empathy for the ways in which flawed human beings struggle to deal with impossible situations. (In his BFI Classics monograph on the film, Dai Vaughan asserts that “Reed seems to hate no one.”)

Odd Man Out launched star James Mason on his international career. Best known before this film for his brooding, often sadistic, romantic roles in Gainsborough melodramas, his performance as Johnny McQueen is remarkable; even before being shot, he seems to be losing his connection with life and the physical world – and with his political convictions: at the start he expresses misgivings about the use of violence in the Cause. Then once he’s wounded he slips into a feverish delirium, sinking ever deeper into himself as all the characters around him react with varying degrees of fear, pity, and distrust, sometimes wanting to help, but increasingly looking for ways to profit from his situation.

And those characters are embodied by one of the finest ensemble casts of the period: Cyril Cusack as the weaselly driver whose fear is responsible for losing McQueen, and who tries to deflect blame onto others, while later carelessly betraying McQueen again; Robert Beatty as the most committed member of the gang, who tries the hardest to find and help McQueen; F.J. McCormick as Shell, a chancer who tries to make a profit by “selling” McQueen to his friends; W.G. Fay as the priest whose only concern is finding McQueen in time to take his confession; Kitty Kirwan as the fierce old woman committed to the fight against the British; Dennis O’Dea as the inspector searching for the man he sees merely as a criminal; Kathleen Ryan as the woman who loves McQueen and makes a fatal choice to be with him; not to mention Fay Compton, William Hartnell, Dan O’Herlihy …

The most controversial aspect of the film among critics is Robert Newton’s larger-than-life portrayal of the mad artist Lukey who sees McQueen’s impending death as an opportunity to commit to canvas the ineffable truth to be found in a dying man’s eyes. Newton blusters and roars his way through the role and has been dismissed as a hammy miscalculation. While there is definitely some truth in this, it’s also true that by the time he shows up, the film has moved deeply into its allegorical phase and Lukey reflects another facet of the uses to which the dying man is put by the people around him. Realism has long since been left behind and so this character seems less damaging than he would have been if the film had remained on a naturalistic path throughout.

Carol Reed’s sense of place (he liked to use actual locations) and character remained strong in his two subsequent films, but after 1949 he never managed to sustain such a perfectly realized balance of elements as in his three masterpieces. Ironically, Reed was finally recognized with an Oscar for the completely theatrical, unrealistic (and greatly softened from the original source) musical Oliver! (1968).

The disk

Criterion’s Blu-ray of Odd Man Out, mastered from a composite fine-grain print made from the original negative, provides a richly detailed image which serves Krasker’s expressive use of darkness and contrast well. The remastered mono soundtrack is very clean and presents William Alwyn’s excellent, and for the time quite experimental, score to its best advantage.

The supplements

There are several informative supplements, beginning with Template for the Troubles: John Hill on “Odd Man Out” (23:50) in which the author of Cinema and Northern Ireland: Film, Culture and Politics talks about the historical background, Green’s novel, and the making of the film. As he points out, the absence of the political situation in the film essentially transforms it into an existential gangster movie, while the removal of Green’s anti-IRA bias and the addition of Reed’s empathy for the characters makes it more complicated as it depicts the characters’ moral dilemmas and failings. Despite the depoliticization, Odd Man Out was the first contemporary British film to deal with the situation in Northern Ireland, in effect the first Irish urban film, breaking with the tradition of rural blarney.

Postwar Poetry: Carol Reed and “Odd Man Out” (15:46) is an interview-based featurette in which several critics and filmmakers discuss the film and its relationship to American noir and French poetic realism; and Reed’s mise en scene and use of the cast, with star James Mason’s performance woven into the multi-character tapestry.

In Collaborative Composition: Scoring “Odd Man Out” (20:40), film music scholar Jeff Smith analyzes William Alwyn’s score in detail, concentrating on the innovative ways in which the film combines the music with sound effects and expressive silences.

Home, James (53:45) is a documentary from 1972 in which James Mason returns to his hometown of Huddersfield. In presenting the rich cultural life of that northern town, the film inadvertently exposes lingering class attitudes, its admiration tinged with a degree of condescension towards the working class. Nonetheless, it’s interesting to see that Mason, one of the most imposing, poised and erudite of English actors, had his roots in a factory town (although from a family more middle than working class).

The final extra is a 1952 episode of the radio show Suspense which struggles to adapt the film (29:23); the final result bears little resemblance to the original despite the presence of Mason reprising his role as Johnny McQueen. It does, however, point to the degree to which Reed’s film is a visual accomplishment.

The accompanying booklet essay is by critic Imogen Sara Smith.

Comments