More recent animation

Since posting about the pleasures of “hand-made” animation the other day, I’ve watched a couple of recent Japanese features which merely reinforce that feeling.

With the international success of Hayao Miyazaki, we’ve come to expect exceptional work from Studio Ghibli, but there’s been a tendency for Miyazaki to overshadow his less prolific studio partner Isao Takahata. This may in part be due to the fact that Takahata’s work tends to be darker and perhaps less family friendly than Miyazaki’s. The grim Grave of the Fireflies is almost unbearable in its realistic depiction of two children suffering and dying in the final years of World War Two; although fantasy, Pom Poko is also savagely violent in its depiction of animals fighting back against human destruction of their environment. There is darkness in many of Miyazaki’s films, but it is often alleviated by notes of hope and redemption. Takahata’s lightest films are Only Yesterday, a lovely reflective piece in which a young woman looks back over her childhood and contemplates where her life is going, and My Neighbours the Yamadas, his most eccentric to date. Yamadas uses a delicate water-colour sketch style to create a surprisingly rich portrait of family life in a series of vignettes.

Takahata’s most recent feature, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013), using a similar though more richly detailed water-colour technique, is not simply Takahata’s greatest achievement: it’s possibly the most exquisite animated film since Lotte Reiniger’s The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926). The folktale-like narrative deals once again with family issues, particularly the pain inflicted by parental expectations imposed on children. A lowly bamboo cutter one day finds a tiny, magical baby inside a bamboo shoot. Taking it home, he’s inspired to change his life in order to launch his daughter’s rise in society to a level he believes she deserves – an ambition which gradually strips away all the joy she has in a simpler life. The artwork and animation are breathtaking, the emotions evoked subtle and deep. Takahata’s view of existence is more melancholy than Miyazaki’s, but his artistry is every bit the equal of his more famous partner.

*

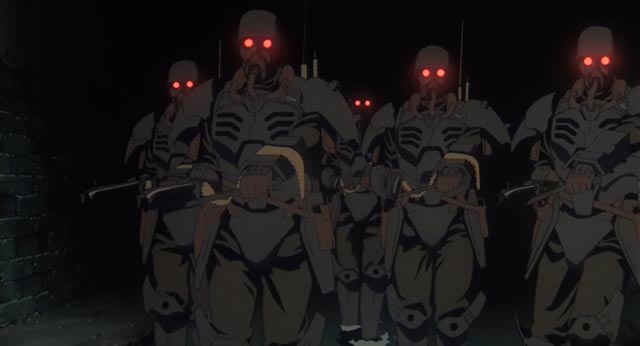

The influence of Studio Ghibli is strongly evident in Hiroyuki Okiura’s A Letter to Momo (2011), although this fantasy-inflected tale of grief and recovery ultimately lacks the technical richness of Ghibli’s productions. Still, with rumours about that the studio is going to stop producing animation now that its two great directors are retiring, it’s good to see that there are others out there trying to fill the imminent void. What is quite unexpected is that this should come from Okiura, whose only previous feature as a director was Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade (1999) – which happens to be one of my favourite animes, a visually stunning, violent dystopian fantasy about a young soldier’s struggle to remain human in a fascist society – and which is worlds away from A Letter to Momo.

In his new film, apparently seven years in the making, there are echoes of Only Yesterday, My Neighbour Totoro and other Ghibli movies. We once again have someone moving from the city to a remote rural area, trying to leave behind a tragedy (the death of a husband and father) and searching for a way to establish a new life. Ikuko is training to become a nurse, which leaves her adolescent daughter Momo alone much of the time. The mother hides her grief in order to protect Momo, but Momo sees this as a lack of feeling and as a result suffers alone with her own grief, which is aggravated by a strong sense of guilt because her last words to her father were spoken in anger.

Being trapped together in these unresolved feelings, it isn’t surprising that supernatural intervention is needed to help mother and daughter heal. This comes in the form of three yokai, monstrous spirits from Japanese folklore which have a pronounced tendency to wreak havoc and interfere mischievously in human lives. Their presence in the house creates problems for Momo because she alone can see them and their penchant for theft, breaking things, and endless eating looks to Ikuko like acting out on Momo’s part. Nevertheless, a bond gradually develops between the girl and the monsters and they eventually help to bring mother and daughter together, dispelling crippling grief and guilt, so that life really can resume again. Less stylistically subtle than Miyazaki’s or Takahata’s work, A Letter to Momo is nonetheless a charming and emotionally resonant feature, skillfully blending comedy with deeper meanings.

*

Very different from either of these, and less satisfying, is Ari Folman’s strange Robin Wright at The Congress (2013), ostensibly an adaptation of Stanislaw Lem’s satirical science fiction novel The Futurological Congress, although I suspect at best it can justify a “suggested by” credit. Set in a vaguely displaced present, the film begins with actress Robin Wright (The Princess Bride, etc) facing middle age and the collapse of her career. Studio head Jeff Green (Danny Huston) offers her a final contract, which her exasperated agent Al (Harvey Keitel) urges her to accept: to be scanned digitally so that her computer doppelganger can go on making movies for the studio without the drawbacks of aging and artistic temperament. The only catch is that she must never appear in person anywhere again to compete with the studio’s property rights. The scanning sequence is the film’s highlight, both visually and dramatically, as it provides Keitel with a powerful monologue to which Wright reacts with a remarkable range of physically expressed emotion.

From this scene, the movie skips ahead twenty years, with Wright heading for the Congress, a vaguely defined other reality in which people take on other identities (all expressed in animation which references multiple styles, particularly Tex Avery and the Fleischers). I must admit that on a single viewing, the film’s terms remained vague for me. I think the idea is that once famous people are scanned into the computer, ordinary people can enter the virtual world and take on celebrity identities. Or something.

The animation is colourful and surrealistic in ways which echo the freewheeling styles of the ’30s, with anthropomorphized objects and shape-shifting people. In this environment, Wright strives to resolve issues arising from having given up her identity and having somehow lost contact with her son who was suffering from some kind of progressively degenerative disease. Apart from the visual invention of the animation, the most interesting thing about the film is the continuity between Wright’s live-action performance and her animated self. Her performance manages to give the film an air of coherence which is not (at least on that first viewing) inherent in Folman’s script.

Comments