Bias and preconception in movie-watching

Any movie is a fixed quantity – well, that was true at least before the boom in home video gave rise to directors’ cuts and variant edits and all manner of alternate versions. But on the whole, particularly for older movies, the film itself is always just what it was when it was first completed and released: the photography is the same (save for scratches and colour fading), the editing is the same (save for print breakage introducing unintended jump cuts and even at times narrative ellipses), the performances are exactly as they were originally captured on film. Yet despite this general truth, it’s not unusual for our perception of a particular movie to change over time. We catch up with an old favourite and find ourselves wondering what the heck we saw in it in the first place; or conversely, for some reason we re-watch something we never liked and find ourselves liking it after all. Of course, it’s not the movie that has changed but ourselves; although we perceive ourselves as continuous entities in time, we actually change in relation to the world around us, shaped and reshaped by experience, by relationships, by the endless stream of events beyond our control. Inevitably, opinion turns out to be a slippery, changeable thing. Our response to any movie – whether we like or dislike it – is rooted more in complex inner factors than what we might deem objective standards of quality or aesthetic value.[1]

I have a friend – intelligent, well-educated, with an interest in philosophy and literature – who adores The Sound of Music, a film I always found to be rather repulsively cloying in its sentimentality. And yet a couple of years ago, working my way through a Fox box-set of Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals, much to my surprise I found myself enjoying the Trapp Family saga, even as I remained fully aware of its clunky emotional manipulations. I couldn’t really say what had changed in me that made the movie’s flaws no longer an obstacle; I was simply entertained by it for the first time.

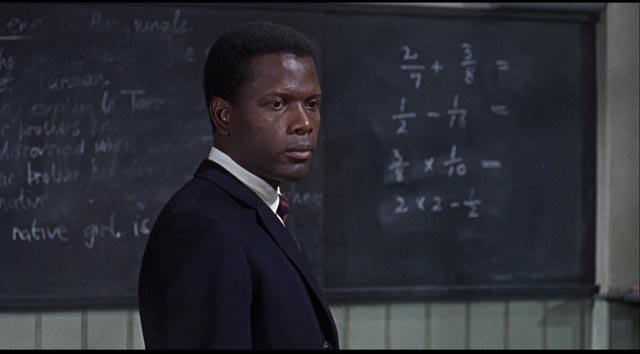

To Sir, With Love (James Clavell, 1967)

Although it seemed just as manipulative as The Sound of Music, I developed a great affection for James Clavell’s To Sir, With Love (1967) the first time I saw it. It struck me as simplistic, naive, overly contrived and highly implausible. However, that first time, I was the perfect age to develop a massive crush on Judy Geeson and that emotional response created a lasting appreciation of the movie.

Much to my surprise, watching it again now, in Twilight Time’s excellent Blu-ray edition, it turns out to be a much better film than I hitherto believed. Rather than naively contrived, it now seems Utopian; rather than a falsification of social reality, it seems to propose an alternative, better society. In watching it again, my long-standing appreciation was greatly deepened. I still have that crush on Judy Geeson, an actress of enormous, unselfconscious charm, but now I no longer feel any need to make excuses for the rest of the film.

To Sir, With Love was based on an autobiographical novel by E.R. Braithwaite, a Guyanese writer and now diplomat with an impressive educational background, culminating in a doctorate in physics from Cambridge University after serving in the Royal Air Force during the Second World War. But being black in post-war England turned out to be an obstacle for Braithwaite; companies wouldn’t hire him because his qualifications would have put him in supervisory positions over white workers, something which was seen as unacceptable. And so he ended up taking a job as a teacher in an East London school. His experiences with his working class students formed the basis of his 1959 novel, the adaptation of which became a labour-of-love for actor Sidney Poitier. Facing skepticism from studio heads, Poitier and others involved took massive pay cuts in order to keep the budget very small (taking percentages instead) just to get it made.

James Clavell was something of an odd choice as writer-producer-director. An Australian who had been working in Hollywood since the late ’50s, Clavell by 1967 was probably best known as the scriptwriter of The Fly (Kurt Neumann, 1958) and The Great Escape (John Sturges, 1963). His work to date as a director was at best undistinguished, starting with the risible Five Gates to Hell (1959), which features gravel-voiced Neville Brand as an utterly implausible Vietnamese warlord who kidnaps a group of nurses during the war of liberation against France in the early ’50s. It’s a sordid, salacious piece of work with an unconvincing Southern California standing in for Asia. The somewhat better Walk Like a Dragon (1960), about anti-Chinese racism in the old West, was followed by a bunch of episodic television work. To Sir, With Love was his third feature and a quantum leap in terms of quality. (Although he subsequently made three more features, the best being 1971’s The Last Valley, he had already started his more successful career as a writer of increasingly epic historical novels by the time To Sir, With Love was released.)

Although the film skirts the edge of social fantasy in its depiction of a self-assured but inexperienced black teacher gradually winning over and instilling self-confidence in a group of discarded, beaten-down white working class kids, Clavell exhibits a fine eye for the details of location and behaviour, drawing terrific performances from the young cast (and the supporting adults who hover around the central story, parents and teachers alike). Clavell’s greatest strength here lies in creating a viable setting for Poitier’s performance, one of the finest of the actor’s career. In almost every shot, we can actually see this teacher thinking, adapting and adjusting moment by moment in ways which slowly break down the kids’ resistance and allow them to see everything that this initially exotic figure has in common with them. Poitier’s Mr Thackeray is the teacher we all wish we had had and we believe every detail of the transformation he inspires in the kids because we want them all to succeed. The climactic scene in which the emotional bond between teacher and students is openly acknowledged and honoured through Lulu’s performance of the title song at the year-end dance, a moment which is in obvious danger of tipping over into schmaltz, is instead richly and authentically expressed thanks to all the groundwork laid down by director and cast.

The idea that all kids, no matter how deprived or beaten down, can be salvaged and set on a positive path is questionable; but as an expression of that ideal, To Sir, With Love is a perfectly realized dream of human potential. There’s not a false note anywhere in the film. Given the period when it was made, with the U.S. still in the throes of the Civil Rights struggle, perhaps the most interesting thing about To Sir, With Love is the way racism – which is nonetheless present as a subtext – is ultimately subsumed by issues of class and made virtually irrelevant by the sense of shared identity which forms between black teacher and white students.

Twilight Time have outdone themselves with this release, enhancing the excellent HD transfer with Criterion-worthy supplements. There are two commentary tracks – on the first, Twilight Time stalwarts Nick Redman and Julie Kirgo are joined by Judy Geeson; the second alternates between author E.R. Braithwaite and teacher and writer Salome Thomas-El. There are a handful of featurettes (produced by Columbia in 2011, but used here for the first time), beginning with a 20+ minute piece in which Braithwaite talks about his life and the origins of the novel. There’s a brief piece in which Lulu talks about the creation of the theme song; a longer piece in which Lulu (looking, in her early 60s, preternaturally young) and fellow-student Michael Des Barres talk about their early-career experiences on the set of the film, focusing particularly on their awe of Poitier and the careful way the actor and Clavell worked with the kids; a tribute to Poitier by agent Marty Baum, who helped get the film made; and finally an interview with Salome Thomas-El, who talks about teaching and the valuable example Poitier’s character provides.

Much to my surprise, this disk has instantly become one of my favourite releases from Twilight Time. Not only did it enable me to recapture the initial feeling I had for the movie when I first saw it more than forty years ago; it has enriched and enlarged that feeling in ways I didn’t expect.

*

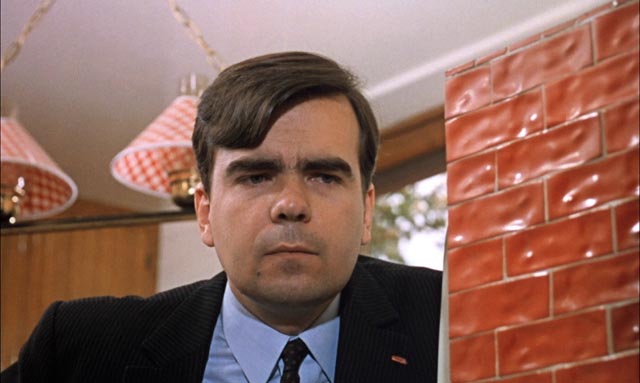

The Bride Wore Black (Francois Truffaut, 1968)

A corollary to the subjective relationship to movies I mention above is the way preconceptions can colour or distort our response when we first encounter a movie. This happened when I recently watched Francois Truffaut’s The Bride Wore Black (1968) for the first time. I understood this to be Truffaut’s homage to both Hitchcock and Hollywood film noir, based as it is on a novel by Cornell Woolrich, whose work has inspired many a noir as well as serving as the source of Hitchcock’s own Rear Window. I was expecting a dark thriller about a woman seeking revenge against the men responsible for the death of her husband on her wedding day, but right from the start there seems to be something implausible about the film. There’s something unnatural about Jeanne Moreau’s appearance at a party which culminates in her shoving a man off a balcony and then walking away unhindered by anyone in the crowd. The murder itself is awkwardly staged.

The film is built around five set-piece killings, but there’s a huge narrative problem underlying them all: no attempt is made to indicate just how the Bride has tracked these men down as there seems to be no way any of them could be connected to her husband’s death. It all seems contrived and oddly random. And yet some of those individual sequences are quite powerful, in particular her snaring of the rather pathetically romantic Coral (Michel Bouquet) and the more complicated relationship she forms with her fourth victim, the artist Fergus (Charles Denner), where her murderous plan is complicated by the unexpected emotional connection she makes with her target. The killing of the arrogant would-be politician Morane (Michel Lonsdale) is utterly implausible, although the scene which surrounds it, in which the Bride insinuates herself into his life by using his young son, is one of the film’s strongest.

Very little of the film’s narrative holds up to scrutiny and its implausibilities continually frustrated me as I was watching it. I kept wondering how an astute filmmaker like Truffaut could make so many fundamental errors on a purely narrative level … because I was expecting something other than what the film actually is – something which was clarified for me by the lively commentary track featuring Twilight Time’s Nick Redman and Julie Kirgo, joined this time by Bernard Herrmann’s biographer Steven C. Smith. Although the background and interpretation they provide can’t entirely redeem the film – even they acknowledge its flaws (and point out that Truffaut himself was ultimately unsatisfied with it, having been in conflict with cinematographer Raoul Coutard and composer Herrmann) – they helped to re-frame the way I was watching it. The Bride Wore Black is not actually an homage to Hitchcock, but rather an attempt to combine Hitchcockian devices with Jean Renoir’s humanistic treatment of character. The mix never gels, but being freed from the expectation of a finely wrought thriller and redirected to look at each narrative unit as an examination of male attitudes towards women (the Bride remakes herself each time into a fantasy projection of each man’s desire, luring them to their deaths by playing on their individual weaknesses), the film becomes a much more interesting examination of gender relations (and, according to Kirgo, a gloss on Truffaut’s own treatment of women in his films).

The Bride Wore Black is not exactly successful as a fully-formed entity, but it turns out to be much more interesting when I set aside those preconceptions. The performances are excellent once the characters are perceived as archetypes, and despite Truffaut’s dissatisfaction with Coutard’s work, the film is vibrantly colourful. The commentary also provides a fascinating lesson in the ways that music can enhance or undermine a director’s intentions (the disk includes the English-dubbed version, because Herrmann’s music cues are used differently in that mix, but I didn’t watch it after sampling a few minutes of the typically jarring disconnect between the actors and their vocal replacements).

Along with the film that immediately preceded it, Fahrenheit 451, The Bride Wore Black represents a brief departure into a stylized unreality which ultimately seems an uncomfortable fit with Truffaut’s typical naturalism. However, Twilight Time’s Blu-ray manages to make even its failures seem interesting.

_______________________________________________________________

(1.) An excellent case in point would be Rodney Ascher’s documentary Room 237, in which five people elaborate on their extremely idiosyncratic readings of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. Projecting their own obsessions onto the film, they insist that Kubrick embedded various codes which they alone were equipped to interpret. Ironically, I found the film fascinating the first time I watched it, amused by the range of subjective experience on display, but then became extremely irritated when I saw it a second time because of the apparent inability of Ascher’s subjects to establish any kind of critical distance which might indicate to them just how absurd their theories are. (return)

Comments