Law, disorder and cynicism in the ’70s

While Jack Smight’s Harper was notable in 1966 as the first big screen detective movie in some while, the genre saw something of a renaissance in the ’70s when it became a useful vehicle for expressing a deepening cynicism (and sense of disappointment) arising out of the political culture of the Vietnam War era and Nixonian corruption. Movies like Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974) and Arthur Penn’s Night Moves (1975) were steeped in ambiguity and social ills rooted in personal moral failings. They embodied the idea that the personal is political in deeply disturbing ways. Films of this period sought to find new ways to use the classical detective figure – some with more success than others. In The Long Goodbye, Robert Altman used Chandler’s Philip Marlowe as a way to critique the genre and also illuminate with a kind of sad nostalgia how the possibility of certainty, of discovering the truth (integral to the classical form) had been utterly lost by the ’70s. Dick Richards, on the other hand, paid homage to the genre with a faithfully period-set remake of Chandler’s Farewell, My Lovely (1975) in which Robert Mitchum was used appropriately to evoke the personality of the ’40s gumshoe. (Less successful was Mitchum’s reprise of the Marlowe role in Michael Winner’s re-make of The Big Sleep [1978], which bizarrely relocated the story to modern-day London, a milieu seriously at odds with the source.)

Cynicism was endemic at that time, and happy endings weren’t considered absolutely necessary. For a few years at least, the opposite was true – unhappy endings became de rigueur with the success of Easy Rider, Bonnie and Clyde, The Wild Bunch, Midnight Cowboy and so on. The best a hero could hope for was personal survival, but cursed with some devastating knowledge that would make life an all but intolerable burden (Jake in Chinatown, Harry Moseby in Night Moves). In thrillers, there was a parallel stream centred on cops who were caught between crime and an at-best dysfunctional, at-worst corrupt establishment – Bullitt (1968), The French Connection (1971), Dirty Harry (also 1971), Serpico (1973). On all sides, society seemed to have become a hopeless mess and it was really difficult for any one individual to retain a sense of integrity.

Hickey & Boggs (Robert Culp, 1972)

A little-known but interesting film from this period has recently been released by Kino Lorber on Blu-ray (and like many disks from this company, it presents a nicely re-mastered image and absolutely no supplements to provide any context for the movie). Hickey & Boggs was the first produced script written by Walter Hill, and the sole directorial effort of actor and co-star Robert Culp. The story is convoluted, marked like many films from the period by a kind of narrative randomness, with characters and events often left unexplained; as with Hill’s later work as a director, there’s a laconic quality which offers a minimum of information to the audience while trusting that viewers will be sufficiently engaged to piece things together for themselves.

Private eyes Hickey (Bill Cosby) and Boggs (Culp) are hired by a man to track down a missing woman named Mary Jane (Carmen Moreno). We see this woman calmly killing a couple of people and, along with a florist (Ron Henriquez), hiding a suitcase full of $1000 bills. This is apparently the loot from a robbery a few years back and what appear to be a number of organized crime figures want it back (among them Robert Mandan and a young Michael Moriarty). People seem to end up dead wherever Hickey and Boggs go and their old connections in the police department (Vincent Gardenia, a very young James Woods) are not happy. The initial case (looking for Mary Jane) pretty much evaporates and the two private eyes are focused on trying to locate the money for a $20,000 reward.

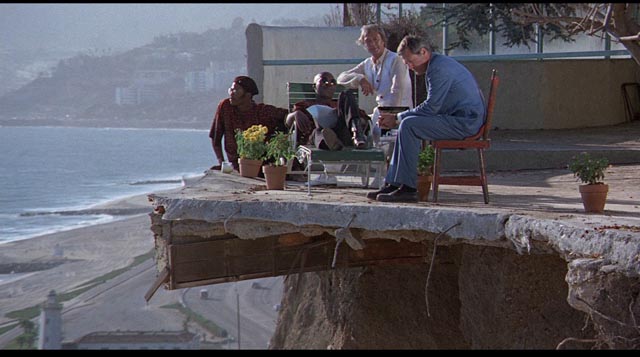

Quite stylishly directed by Culp, Hickey & Boggs is gritty and casually violent; the two partners cooperate with the police only to the degree that it helps them to get closer to the money. Both men try to deal with broken relationships (Rosalind Cash for Hickey, Sheila Sullivan for Boggs). Not surprisingly, it all ends in a bloodbath. As the pair comment several times, their work no longer means anything. Nothing is ultimately accomplished, nothing resolved – many people have simply died over a bag of money.

At the time of the film’s release, audiences may have been taken by surprise by its relentlessly downbeat tone. Culp and Cosby were known for their comedy-inflected espionage series I Spy, which ran on television from 1965 to ’68, and Cosby at the time was a successful stand-up comedian. Their relationship in the film is a soured version of their TV rapport, almost a rebuke of the off-hand fantasy offered by the show. Those years together serve the film well as with little effort they convey a deep and lasting connection between Hickey and Boggs. Of course, today the film is further complicated for the viewer by the recent accusations made against Cosby by a number of women, raising once again the issue of how – or whether – we should disconnect the real life of a celebrity from the work they do or, as in this case, did a long time ago.

*

Brannigan (Douglas Hickox, 1975)

By the early ’70s, the political situation had rendered John Wayne, one of Hollywood’s biggest stars, virtually persona non grata with large segments of the contemporary audience; this symbol of rugged American individualism was a staunch right winger and the counter-culture could no longer see past the politics to his considerable virtues as an actor. This attitude also glossed over some of the more nuanced aspects of his decades-long career (just as Clint Eastwood’s career would eventually embody a self-critique of its more overtly reactionary elements); in fact, Wayne’s success as an actor (rather than simply a star) was most firmly established by the problematic characters he played in Howard Hawks’ Red River (1948) and John Ford’s The Searchers (1956), both flawed, violent representatives of the anti-social dark side of that individualism. The misbegotten, jingoistic The Green Berets (1968) sealed the contempt of the counter-culture, and yet Wayne remained popular with an older audience (and the following year he finally won his Oscar for True Grit); in fact, he won the People’s Choice Award for favourite movie actor four years in a row in the ’70s.

Although westerns were falling out of favour by the late ’60s, Wayne continued making them on and off until the end of his career – in fact, his final film was Don Siegel’s elegiac The Shootist which, something like Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven, was a summary of the star’s western persona. But while Eastwood, looking back over his career in the genre, discovered a monster, Wayne went out with a portrait of tragic nobility – the star dying of cancer playing an aging gunfighter also dying of cancer. The sense of identity between actor and role helped to begin something of a re-evaluation of Wayne’s career in a more positive light.

But before that, he had in two instances stepped out of his familiar western persona into the contemporary world, the cowboy transformed into a modern-day equivalent: the cop. Eastwood had made the same move with great success in a pair of movies by Don Siegel: Coogan’s Bluff (1968), which deliberately conflated the western and the cop movie by casting Eastwood as an Arizona sheriff displaced to New York when he’s sent to the big city to bring back a fugitive (the film was later adapted into the successful Dennis Weaver TV series McCloud, which ran for seven seasons); and the hugely influential Dirty Harry (1971). Rumour has it that Wayne turned down the role of Harry Callahan; if true, it seems like a wise move as he would have been in his mid-’60s at the time and not suited to the action-oriented story. But the success of Dirty Harry no doubt nudged him into taking on the lead in John Sturges’ McQ (1974). However, he was reportedly uncomfortable with that film’s cynical attitude towards a corrupt police culture. The following year, he found a more suitable project in Douglas Hickox’s Brannigan (1975).

In Brannigan, Wayne stars as an unorthodox, rule-bending Chicago cop who (like Coogan before him) is uprooted from his home turf to go and retrieve a fugitive. In this case, he’s sent to London to collect slick gangster Larkin (John Vernon, who a few years earlier had played the Mayor of San Francisco in Dirty Harry). Although the story cooked up by four writers (Christopher Trumbo, Michael Butler, William W. Norton, and William P. McGivern – whose venerable history in the genre includes Fritz Lang’s greatest noir, The Big Heat) is convoluted – Larkin is kidnapped while under police surveillance and Brannigan and Scotland Yard are toyed with contemptuously by the kidnappers – much of the movie is played for comic fish-out-of-water effect. Wayne is a massive presence whose frontier attitudes (he insists on keeping his gun although it’s illegal in England) bemuse rather than offend Scotland Yard’s Commander Swann (Richard Attenborough). There’s a feeling that the excellent British cast are paying deference to the larger-than-life American star; but there’s no arrogance in Wayne, whose easy manner indicates respect for his co-stars, not least in the case of Judy Geeson as the policewoman assigned to be his driver (and minder) during his stay. A genuine affection develops between Geeson/Jennifer and Wayne/Brannigan which provides the film with an amiable charm despite the more routine elements of the thriller plot.

The sometimes clunky script is efficiently executed by director Hickox (Theatre of Blood, Zulu Dawn), and versatile cinematographer Gerry Fisher does a fine job of making London a real presence in the story. Here, what cynicism there is is restricted to a lack of honour among thieves; the police are all positive figures and Brannigan’s transgressions (occasionally roughing up or threatening an informant) are simply old-school tactics lacking the pathological element of Harry Callahan’s rule-breaking. Brannigan is a minor footnote in Wayne’s career and the kind of disposable entertainment Hollywood used to toss off routinely before becoming addicted to the quest for blockbusters.

Twilight Time’s limited edition Blu-ray has a slightly soft but colourful image, with their usual isolated audio track highlighting Dominic Frontiere’s score, plus an engagingly chatty commentary by Nick Redman with Judy Geeson, who has fond memories of working with Wayne. There are also a few minutes of super-8 behind-the-scenes footage of Wayne shot by Geeson.

Comments

Great piece. I remember these films well. The theater in which I saw Hickey and Boggs (I was 13 at the time) had a vehicle in the lobby riddled with bullet holes and life-sized Culp and Cosby cardboard figures standing in front of it. I also remember a funny line from the movie, after Boggs empties his revolver at a fleeing car and hits nothing. he turns to Cosby and says “I gotta get a bigger gun.” Next time you see him, he has HUGE revolver. The Manitoba rating for the film at the time was “Adult Not Suitable for Children”, with a warning about explicit violence, sex, nudity, and homosexuality. I don’t recall any of the sex or the homosexuality. Could have been implied by the relationship between Hickey and Boggs, I guess. It was certainly violent, though. Another film a couple of years later reminded me of it: Freebie and the Bean, with Alan Arkin and James Caan, though I think it was a comedy.

I guess I must be more jaded than your younger self as all the seediness in Hickey & Boggs barely caused a ripple for me. As for the “homosexuality”, it seems to be implied that the guy who hires them to track down Mary Jane is probably a pedophile, but even their serious problems with their ex-wives don’t seem to trigger anything of that order between the two detectives!

And yes Freebie and the Bean was a supposed comedy, though I always thought it was really strained and unfunny. Certainly disappointing from the director of The Stunt Man.