An evening of Guy de Maupassant on film

I couldn’t say now exactly when I first encountered the work of the 19th Century French writer Guy de Maupassant. I think it was in my early teens. I remember having a hardcover collection of his stories, which I probably got from somewhere like the Book-of-the-Month Club. The appeal at that time was the fact that he had written some horror stories – which I later discovered had been quite influential on writers like H.P. Lovecraft and Ambrose Bierce. Some of these stories had a fairly bleak view of human beings and the universe they inhabited. Probably his best-known horror story is “The Horla” (1887), in which the protagonist is haunted and driven mad by an invisible hostile entity; this is the model for many of Lovecraft’s stories. The short, and even more chilling, “Diary of a Madman” (1885), is a more realistic depiction of human evil in which an upright and respected judge becomes obsessed with the idea that to kill is the most natural and primal act to which all life is compelled; after his death from old age, notes are discovered in his desk which describe his “philosophy” and the murders it has led to – including condemning an innocent man to the guillotine for a crime the judge himself committed.

I just bought the complete works of de Maupassant for my Kindle because the other day my friend Howard Curle came over for an evening and we ended up watching a de Maupassant double bill. We started the evening with Criterion’s stunning Blu-ray of Jean Renoir’s Partie de campagne (A Day in the Country, 1936/46), based on the 1881 story “A Country Excursion”. This film, conceived as a short which could be included in an omnibus feature, might appear to be a trifling diversion from Renoir’s leftist political convictions at the time, but as scholar Christopher Faulkner explains in an informative interview on the disk, the film represents Renoir’s cinematic attempt to come to terms with the legacy of his father, the great Impressionist painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir. This elegant, touching comedy, which ends on a delicately tragic note, is full of echoes from Renoir pere’s work (and that of other Impressionists), with images of petit bourgeois Parisians enjoying nature on the outskirts of the city.

The film depicts an excursion of the Dufour family in a borrowed horse-drawn milk cart to an idyllic spot on the banks of a river where they stop at an inn for a picnic lunch. There’s the shopkeeper father (Andre Gabriello), the matronly mother (Jane Marken), romantic daughter Henriette (Sylvia Bataille), somewhat cranky grandmother (Gabrielle Fontan), and shop assistant Anatole (Paul Temps). As mother and daughter enjoy the swings behind the inn, they are watched by a pair of opportunistic young men, Henri (George D’Arnoux) and Rodolphe (Jacques Brunius), who for their own amusement decide to try to seduce the two women. That is, Rodolphe proposes the game, while Henri expresses indifference. Polite and amusing, they insinuate their way into the family group and manage to convince Monsieur Dufour to allow them to take mother and daughter out on the river in a couple of skiffs. Unexpectedly, Henri finds himself falling for Henriette and, as they pause on the riverbank in the shade of some trees in which a nightingale is singing, she gradually succumbs to his – and her own – desire. At this emotional moment, the weather abruptly breaks and there’s a visually stunning montage of a rainstorm on the river, after which a title card tells us that years have passed.

We again meet Henri boating on the river, revisiting the site of that intensely romantic moment, the formerly diffident man now melancholy. There he finds Henriette again, beside her the sleeping shop assistant Anatole. She tells Henri that she and Anatole are now married, but that every day she thinks of this place and that long-ago moment; the pair are bound by a mutual sense of lost possibility, of a path not taken. And this light and delightful little comedy ends on an aching note of sadness.

Although conceived as a short film, because of weather and resulting budget issues, A Day in the Country went over schedule and Renoir abandoned it to move on to his next feature, The Lower Depths (1936). Some additional shooting took place under the direction of Renoir’s assistant Jacques Becker, but by that time pretty much everyone had soured on the project. The film was set aside but, remarkably, all the elements survived the war and the Occupation. Although there were apparently sequences left unfilmed (particularly a prologue and late scene set in M. Dufour’s shop), and Renoir himself had long been in exile in the States, his long-time partner Marguerite Renoir along with her sister Marinette Cadix edited the existing footage (with a couple of very brief explanatory titles at the beginning and end) and this is the version we now have. Despite its status as something of an orphan among Renoir’s works, the film seems almost perfectly formed; its lightness of touch, its nuanced observation of characters who could so easily have tipped over into caricature, and its striking modulations of mood make it every bit as satisfying as the major features.

It turns out that the proposed opening, introducing the Dufours’ in their Paris shop as they prepare for the excursion, was invented for the script, but the penultimate scene to be set again in the shop is part of the original story – Henri pops in and speaks to the mother, discovering that Henriette has married Anatole; as he is leaving, she asks after Rodolphe and tells Henri to ask his friend to come by as she’d like to see him again. The final scene of the story is exactly how the film ends. In fact, apart from that one missing scene, the adaptation is remarkably faithful to de Maupassant in its incidents and structure. In tone, however, Renoir has softened de Maupassant`s satirical treatment of class, adding a warmer, more affectionate view of the characters and deepening the story’s emotional resonance; he shows in the actors’ faces things which can only be hinted at in the original prose.

This difference between print and screen reaches its peak in that climactic scene between Henriette and Henri. The event is the same – the young, romantic Henriette, influenced by the heady natural environment, impulsively loses her virginity to her seducer – but the expression of the scene is very different. As Renoir, a filmmaker who preferred long takes and wider shots, moves in for perhaps the most striking close-up of his entire career, we are given privileged access to Henriette’s complex emotions; at her moment of surrender, she turns towards the camera and a tear rises in her eye – at this moment when her life is transformed, pain, joy, fear and an awareness of inevitable loss are all contained within her pleasure … a potent mixture of feelings which are reinforced and yet swept away by the magnificent montage of the rainstorm which immediately follows, all the power of nature sweeping away fragile human feelings with the inexorable passage of time. This is a masterful display of the expressive capacities of cinema and perhaps the key creative moment at which Renoir asserts his own artistry in answer to his father’s.

A similar faithfulness to and cinematic enhancement of the author’s work is also apparent in the second film Howard and I watched that evening: the Val Lewton/Robert Wise production Mademoiselle Fifi (1944). This was the Editions Montparnasse DVD I bought in Paris back in 2010. Although the image quality is acceptable, it’s a pity that this film hasn’t been restored and remastered – Lewton is so irrevocably associated with his nine classic horror films (from Cat People in 1942 to Bedlam in 1946), that his other work has been unjustly neglected, this feature in particular. Based on two of de Maupassant’s short stories – “Boule de Suif” (1880) and “Mademoiselle Fifi” (1882) – set during the Franco-Prussian war (1870-71), the film centres on the pretty young laundress Elisabeth Rousset (Simone Simon) travelling by coach from the city of Rouen to her home town. The coach is also carrying three bourgeois couples hoping to escape from occupied France, a young priest (Edmund Glover) going to take up a post in Elisabeth’s village, and the liberal would-be revolutionary Jean Cornudet (John Emery).

The script by Joseph Mischel and Peter Ruric does an intelligent job of combining the two stories, although they can’t avoid a certain structural awkwardness about two-thirds of the way through when the narrative switches from “Boule de Suif” to “Mademoiselle Fifi”. Those first two-thirds focus on issues of class which are highlighted by the effects of the occupation. The bourgeois characters – a count, a wine merchant, a mill owner and their wives – have accommodated themselves to the occupation, their concern only with how current events might affect their financial interests. Elisabeth, however, is a feisty patriot who despises the invaders. She is also lower class and viewed with disdain by her betters, although as the journey bogs down on snowy roads and it turns out that she is the only one who had the forethought to bring along food and drink, the others set aside their condescension to accept her offer to share her provisions.

When the coach stops for the night at a small inn, the Prussian officer in charge summons Elisabeth. She’s inclined to refuse, but the count assures her it must just be some technicality. When she returns shortly afterwards, she says nothing about her meeting; but the next morning the party discover that the horses have not been tethered to the coach and the officer refuses to allow them to move on. When it turns out that they are being held up because Elisabeth refuses to dine with him, initially the group support her patriotic stand. But as the days pass, they begin to lose patience and finally exert all their influence to get her to accept for the good of the group. Although the officer has made his demand simply to break her spirit, to show that he has power over her although no actual interest in her as a woman, her fellow passengers assume that he wants to have sex with her and they celebrate her “sacrifice” by throwing themselves a party with champagne. Although they pushed her into this situation, the next day they shun her with contempt because, in their eyes, she’s no better than a prostitute and not worthy of their attention. To reinforce their contempt, they now refuse to share their own food with her, despite her earlier generosity.

When the coach arrives in her village, Elisabeth and the priest disembark and these contemptible people exit the scene. Cornudet, shamed by their treatment of her and his inability to come to her defence, stops the coach and gets off, going back to look for her. But she has no interest in him or his ineffectual politics.

Now it turns out that the same Prussian officer has arrived at the local garrison and he and his men, billeted at an opulent mansion which they have systematically ruined out of boredom, decide to have a party. One of the soldiers collects the girls from the laundry, including Elisabeth; the other girls enjoy the food, wine and fine clothes they are given, but Elisabeth can barely contain her fury. When the officer provokes her by heaping contempt on the French and their nation and finally declares that the Germans own everything, including all French women, she stabs him to death and flees. This action marks the beginning of an active resistance and the young priest and a now-inspired Cornudet hide and protect Elisabeth, who takes on a symbolic value which combines the historical figure of Joan of Arc (alluded to in the film’s opening scene) and the contemporary Resistance active in France under the Nazi Occupation.

Again, as in Renoir’s film, this adaptation is remarkably faithful to the source stories if one makes allowances for the necessary adjustments to combine the two. The officer in “Boule de Suif” is unnamed, while the girl who kills the officer in “Mademoiselle Fifi” is a young Jewish prostitute. In fact, the biggest change is in the character of Elisabeth herself: in the original story, she is indeed a prostitute, which increases the anger of her bourgeois companions – why, they demand to know, is she unwilling to give herself to the officer (for their convenience) when she makes her living from giving herself to all kinds of men? Her patriotism seems like a ridiculous affectation to them. By changing her in the film to a laundress – although no doubt necessitated by the restrictions of the Production Code – the script reinforces a left-wing critique which seems surprising now in a studio film of the period. The conflict is between a corrupt and self-serving privileged class and a moral and politically committed working class; by implication the film is condemning the accommodations made by that privileged class, the collaboration of the Vichy government with the Nazis, while extolling the left-inflected Resistance as the genuine spirit of French nationalism.

Needless to say, Robert Wise’s direction in his first feature is nowhere near as richly expressive as Renoir’s, although the film displays the same attention to production design and atmosphere as Lewton’s horror movies, and Wise does manage to draw fine performances from most of the cast, with particularly sensitive work from Simon.

As for the film’s title, taken from the second de Maupassant story, it remains somewhat confusing. I had always believed that it referred to the central character, the young laundress, and even after watching the film five years ago my memory slipped back into that error. Mademoiselle Fifi is actually the nickname given to the Prussian officer by his comrades. In the story, he’s boorish and violent and yet somewhat effeminate. Why Lewton chose to use this as the film’s title is puzzling as the officer is by no means the focal character and the significance of the name is never made clear – although by projecting this character back into the “Boule de Suif” part of the narrative, an interesting subtext is added, with the implication that the officer’s desire to humiliate Elisabeth is rooted in repressed homosexuality.

What is clear from both these films is that de Maupassant’s facility with narrative and the psychology of character is remarkably modern and lends itself with ease to cinematic adaptation. I was surprised, reading these three stories immediately after watching the two films, at how much of what was visible on screen could be traced back to the original prose. It’s easy to understand why there are more than two-hundred adaptations of his work listed on IMDb.[1]

NOTE

The Criterion Bu-ray, in addition to Faulkner’s interview about the production, includes one of the familiar Renoir introductions from when his films were shown on French television in the ’60s, this one very lively and discursive: Renoir’s personality comes across as very much like his films – warm and generous and full of self-deprecating humour. (Although the story of this particular production also shows that he could be prickly and difficult.) There’s a brief interview with producer Pierre Braunberger, dealing with the troubled history of the production, plus two substantial pieces provided by the Cinematheque Francais: an 89-minute compilation of outtakes from the production which provide a look at Renoir’s meticulous directorial process – all the more surprising given the light, improvisational feel of his work – and ten minutes of screen tests, which show Renoir experimenting with both camera angles and the facial expressions of his cast. Faulkner provides one additional piece in which he analyzes what these outtakes and screen tests reveal about Renoir and his work. The booklet essay is by film critic, theorist and historian Gilberto Perez.

It’s a pity that Criterion couldn’t also include the commentary Philip Kemp recorded for the BFI DVD released in 2003. While Kemp goes over a lot of the same ground as the Criterion supplements, he adds some interesting observations and more detail about the collapse and resurrection of the production, including a description of Jacques Prevert’s attempt to write an entirely new feature-length script around the existing footage, turning it into an attack on capitalism – an idea which we can be thankful was abandoned.

_______________________________________________________________

(1.)

One of the best of these many adaptations is Walerian Borowczyk’s Rosalie (1966, available on Arrow’s Blu-ray edition of Borowczyk’s short films and animation), his first live-action film, based on the very short story “Rosalie Prudent” (1886), in which a servant on trial for killing her newborn baby tells her story of being seduced by her employer’s nephew, becoming pregnant, and facing an inevitably difficult future. Borowczyk strips away the courtroom, the judge, the other characters, and has Rosalie (Ligia Branice) face the camera in medium close-up, dressed in white against a white background, to deliver her wrenching monologue. He cuts away repeatedly to the items of evidence laid out on wooden tables – a photo of the nephew, her sewing box and the clothes she had been making for the baby (which, turning out to be twins, were simply more than she could bear), the shovel she used to bury them, and the roughly wrapped bundles she had buried them in. As her story continues, each item fades away as if her narrative of class oppression, in being shared, gradually wipes away her guilt. Rosalie is a minimalist tour de force which transforms de Maupassant’s realistic narrative into something more ethereal, even transcendent.

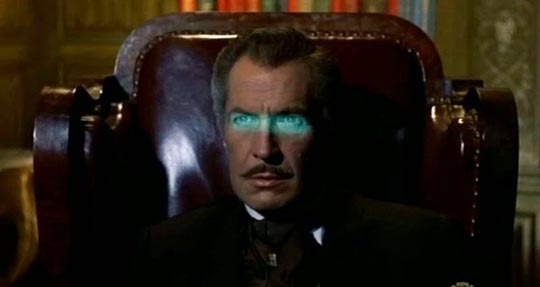

Much less elegant is Reginald Le Borg’s Diary of a Madman (1963), released as part of Shout! Factory’s third box set of Vincent Price movies. This attempt to emulate the Corman-Price Poe movies, like Mademoiselle Fifi, conflates two de Maupassant stories but, unlike Wise’s film, manages to completely distort the author’s original intentions. By taking the central structure of the title story – an upright judge who secretly commits murder – and throwing in the sinister invisible entity from “The Horla”, Le Borg and writer-producer Robert E. Kent provide an external, supernatural motivation for crimes which are given a very dark, psychological impetus in de Maupassant’s original. Here, instead of an innate homicidal impulse in nature in general and human beings in particular, evil becomes an external force manipulating essentially good people into committing horrific acts. This distortion is just one of the movie’s flaws – Le Borg was a merely competent (at times) journeyman with no visual flair and a perfunctory way with actors. Vincent Price does his best with the lead role, but he’s surrounded by a supporting cast which is very uneven, while the production design is blandly unimaginative. As for the Horla itself, Le Borg apparently wanted to give it a distorted, unearthly voice, but producer Kent insisted on a straightforward, ordinary voice … which pretty much kills any possibility of generating an eerie atmosphere (although there are moments when Joseph Ruskin’s voice sounds a little like Price, which almost hints at the whole thing being a delusion after all conjured up by his sick brain … almost). (return)

Comments