The political cinema of Costa-Gavras

The Greek-born, French-based filmmaker Costa-Gavras became an international success with his third feature, Z (1969), a dynamic political thriller based on the assassination of a Greek leftist politician and the subsequent seizing of power by a right-wing military junta. The film’s anger and openly leftist attitude drew on the political upheavals of the late ’60s, though perhaps it was the sheer dynamism of its technique that won it an Oscar from the generally conservative Academy. Not only did Z put Costa-Gavras on the cinematic map; it provided a template which would serve him well in a series of political films over the next couple of decades. Unlike the more rigorously theoretical approach of Gillo Pontecorvo in The Battle of Algiers three years earlier (also nominated for an Oscar, though it lost to Claude Lelouch’s lush romantic melodrama A Man and a Woman), Costa-Gavras had brilliantly embedded the film’s politics within an exciting – and commercial – genre movie. The strength of Z, a film which remains an exemplary piece of politically-committed popular entertainment, is that he managed to keep the politics sharply focused while simultaneously providing those commercial thrills. It was a balancing act which few other filmmakers were capable of achieving.

In Costa-Gavras’ subsequent films, it could be argued that he never quite managed to repeat this feat; it could also be argued that in dialing back the visceral excitement of Z, he made deeper, more resonant films – particularly in The Confession (1970) and State of Siege (1972), both newly released by the Criterion Collection in excellent Blu-ray editions. These two features form with Z a loose trilogy which dissects the uses of and reactions to political violence across the entire spectrum from left to right.

The Confession (1970)

Feted as a voice of leftist anger for Z, Costa-Gavras made what might have seemed a surprising move by immediately following it with The Confession, a brilliant depiction of the internal functioning of a repressive state behind the Iron Curtain. The film was adapted from former Czech vice-minister of foreign affairs Artur London’s personal account of one of the last of the Stalinist show trials (in Prague in 1952), in which 14 high-level members of the government (mostly Jews) were arrested and tortured into “confessing” political sins of which they were not guilty. Eleven were executed, three – including London – survived.

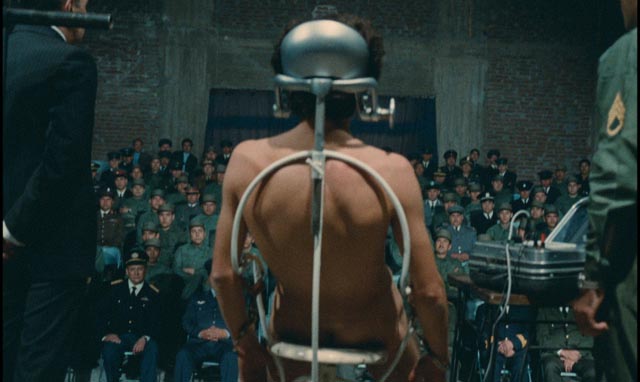

The Confession (adapted by Jorge Semprun, who also wrote Z) is as exciting as Z, but in a different way – it replaces the visceral action of the earlier film with internal drama. It remains Costa-Gavras’ greatest film, flawlessly crafted, superbly acted. Yves Montand as London (following his brief appearance as the assassinated deputy in Z) gives a remarkable performance which allows the viewer to experience every painful detail of the methodical torture (sleep-deprivation, starvation, thirst, physical beatings) while simultaneously understanding his incremental submission to the demands of his tormentors. He proves once again that the camera can actually see what an actor is thinking; much of the film plays on Montand’s face as he silently absorbs what is happening to him and gradually accepts his role as a sacrifice to the Party’s agenda. Simone Signoret is forceful as London’s wife Lise, also a committed believer, who has to deal not only with continuing her life under the cloud of her husband’s arrest, but also with the uneasy thought that since all this is happening, he must in fact be a traitor to the cause. Gabrielle Ferzetti, an Italian actor with a long and prolific career (he starred in L’avventura and was the villainous, crippled railroad baron in Once Upon a Time in the West), is a superb match for Montand as the calm, methodical interrogator who constructs London’s confession line by line out of small, individual facts stripped of context and explanation, finally combining them into a damning “truth” against which there can be no defence.

The term “confession” has several layers of meaning beyond the most obvious one; what becomes clear through the process of breaking London down is that he is caught within an essentially religious system – belief in the Party is akin to belief in God, a matter of faith, with believers giving up all personal responsibility to the Party apparatus. The Confession, through its detailed depiction of the step-by-step process of getting a believer to admit his “sin”, echoes the point made by George Orwell in Nineteen Eighty-Four: when one’s identity becomes inseparable from the ideological system one is a part of, the inevitable end point is complete submission to the system which is intent on destroying one. The parallels to the Catholic Church and the Inquisition are clear: these show trials are a form of moral drama with every participant – defendants, prosecutors, judges – playing carefully conceived roles in order to confirm and reinforce the established structures of power. Actual guilt or innocence are irrelevant to the purpose.

Although common sense still resists the idea that people can be manipulated into confessing to crimes they haven’t committed, The Confession makes this subtle process absolutely clear. Not only do London and his co-accused finally sign elaborately fabricated confessions to being spies for the West; they come to see that even though these confessions are lies, it is their duty and responsibility to the Party to go through with the charade – their sacrifice can, they are convinced by their tormentors, only strengthen the cause of Socialism by guiding others onto the right path. As O’Brien tells Winston Smith in Nineteen Eighty-Four: “In time you will come to love Big Brother.” Indeed, even years after his ordeal, London retained his socialist convictions. It’s not the political philosophy which is to blame, but rather the corrupt misuse of power.

This last point was lost on many critics and viewers at the time of the film’s release, with the Left seeing it as a kind of betrayal (particularly coming on the heels of Z); it was seen as giving ammunition to the enemies of the Left. And yet, in essence this film is analyzing and condemning the same things as the earlier film – the misuse of political power and the ways in which violence crushes independent thought and props up illegitimate political systems.

State of Siege (1972)

These themes are further elaborated in Costa-Gavras’ next film, State of Siege (1972). Again based on an actual incident, this one deals with the kidnapping and murder of an American in Uruguay in 1970. In the actual case, former small town policeman and FBI agent Daniel A. Mitrione (renamed Santore in the film and played again by Montand), working for the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), was kidnapped along with two other foreigners by Tupamaro guerrillas. This group initially intended to use their hostages as bargaining chips for the release of political prisoners, but the action backfired; with their demands unmet, the Tupamaros found themselves backed into a corner and their execution of Mitrione ended up strengthening the oppressive U.S.-backed government.

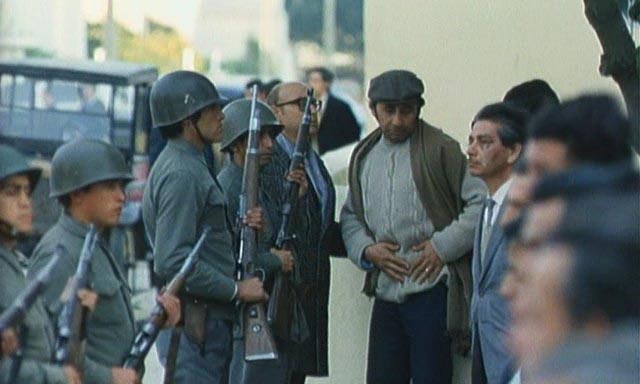

The film (scripted by Franco Solinas, who had previously written The Battle of Algiers for Pontecorvo) begins with the city of Montevideo locked down by the military as they search for the hostages; when Santore’s body is discovered in a car parked on a side street, the narrative circles back a week to fill in not simply what happened, but why, and most importantly just who Santore was. The kidnapping operation, taking place simultaneously in multiple locations, is a bravura display of visual storytelling. It lays out not just the organizational skills of the Tupamaros, but also subtly suggests their acceptance by the local population; in a series of carjackings to obtain the necessary vehicles, drivers accept with some equanimity these thefts by a group which had until then been largely non-violent, with a kind of Robin Hood image. The drivers are all taken for escorted 30-minute walks before being released to report the vehicle thefts to the police, giving the Tupamaros sufficient time to carry out their operation.

At the centre of the film is a series of conversations between Santore and his captors which gradually expose the truth behind Santore’s public role as an advisor to the Uruguayan police on “communications and traffic control”. The American’s function in several South American countries over a number of years has been the training of police in methods of torture and terror, encouraging if not directly establishing death squads to eliminate political dissidents and union activists. These discussions form a dialectical confrontation between two radically different views of the world. At one point, exasperated, Santore claims that he stands for the defence of “freedom, democracy and Christian civilization” against forces determined to destroy them, a fight which justifies the use of any means (including, without irony, the crushing of others’ freedom and democracy). His captors argue that they stand for social justice against the depredations of powerful elites which exploit ordinary people in favour of U.S. corporations.

As in Costa-Gavras’ previous films, the root of political evil is the absolute certainty of righteousness which leads inevitably to violence against those who disagree. The counter-insurgency techniques exported by the U.S. to Latin America produced an increase in brutal repression which in turn resulted in increasingly violent resistance, which of course resulted in escalating repression and so on and so on … The most chilling moment in the film comes when Santore admits that he completely understands his captors’ motives and also understands that his own people will sacrifice him rather than rescue him; he’s worth more dead than alive now, because his death will justify further oppression and greater control by those who run the country in the interests of their own class. In fact, shortly after the events depicted, the military took control of the country and put an end to the inconvenience of democracy.

Together, Costa-Gavras’ trilogy analyzes a broad range of “legitimate” and “illegitimate” uses of violence. Z shows peaceful protest met with assassination; The Confession depicts a paranoid system which attacks itself in order paradoxically to maintain itself; and State of Siege shows how violent repression inevitably produces violent resistance. The murder of Santore is ultimately a self-defeating blow against repression; as the Tupamaros agonize over their options, it becomes clear that to release him with their demands unmet merely proves their own powerlessness, and yet to kill him guarantees increased repression and ensures once again their own powerlessness. State violence is “legitimate” because it is used to preserve “order”. The question is always: whose order? Obviously what is being preserved is always the privilege of the dominant class. The violence from below which is provoked by the harsh status quo is always designated as crime or, more likely, terrorism. State violence remains in a way “invisible”, leaving those striking from below to take the full burden of disorder. When the Tupamaros turned from resistance to murder, they began losing the support they had previously had from the population.

Costa-Gavras’ treatment of these issues is more nuanced in both The Confession and State of Siege than it was in Z, where there was a certain degree of caricature in his treatment of the Right. Although widely praised for Z, he was criticized from the Left for The Confession and by some American commentators for State of Siege, yet taken together these three films offer a fascinating analysis of the dynamics of power as it works within socialist, fascist and capitalist systems. Although the director’s sympathies are quite obviously leftist, he is not willing to paper over the crimes of the Left and remains surprisingly even-handed in his treatment of Santore; he is a humanist rather than an ideologue.

Stylistically, these two films are quite different. The Confession (shot, like Z, by the great Raoul Coutard) is classical in form, a work of great formal beauty with fluid camerawork, a rich colour palette and a subtle use of sound (there is very little music and an intricate use of ambiances and silence to reinforce the interiority of the narrative). State of Siege is grittier and more ragged, using a more immediate documentary-style (shot by Pierre-William Glenn). The opening scenes of the city under martial law prefigure similar images from Missing (1982) – ironically, as State of Siege was shot in Allende’s Chile a year before the U.S.-backed coup which was the subject of the later film.

Costa-Gavras learned his craft in France in the early ’60s by working as an assistant to several major filmmakers – Rene Clair, Rene Clement, Henri Verneuil – all of whom had been derided by the New Wave. It’s interesting that, given his progressive political attitudes, his own work followed in their footsteps rather than taking one of the more radical paths mapped out by a contemporary like Jean-Luc Godard, whose political beliefs had such a forceful impact on his own filmmaking practice. While such a comparison can make Costa-Gavras appear conventional, the skill with which he uses classical techniques is capable of bringing the politics to a far broader audience. It could even be argued that the pleasures afforded by his elegant use of camera and editing (the superb wordless opening sequence of The Confession which immediately establishes a deep sense of paranoia which underlines everything which follows; the equally wordless kidnapping sequence in State of Siege, which quickly establishes the nature of the Tupamaros) may help an “average viewer” to take in the political arguments where the more difficult intellectual approach of Godard more often alienates the viewer. Is this suspect and unduly manipulative? Possibly, but then every technique of art strives to manipulate the perceptions of its audience, Godard’s no less than Costa-Gavras’, and in the end the ideas need to be judged on their own merits.

Although Costa-Gavras continued to make movies until just a few years ago, none of his subsequent work (with the exception of Missing) has had the impact of the trilogy, three films which sprang seemingly organically from the major social and political upheavals of the ’60s and which managed to blend rigorous political ideas with gripping drama.

The disks

Criterion’s Blu-rays present both films in 1.66:1 transfers scanned and restored at 2K. The Confession has a rich film-like look with strong contrast (it’s a fairly dark film). State of Siege has a rougher look, with more prominent grain and a greater use of hand-held camera. Both restored mono soundtracks are clean and clear: The Confession has the more subtle soundscape, while State of Scene has more overt energy, supported by Mikis Theodorakis’ prominent score.

The supplements

Criterion provides strong supplements for both movies – more for The Confession than for State of Siege. On the first disk, there’s a documentary shot by on-set photographer Chris Marker, You Speak of Prague: The Second Trial of Artur London (31:04), which focuses on the politics of the film through interviews with various participants, including Costa-Gavras, original writer Artur London, adaptor Jorge Semprun, and actors Yves Montand and Simone Signoret. Costa-Gavras at the Midnight Sun Film Festival (1998, 1:04:49) is a long conversation on stage between filmmaker Peter von Bagh and the director, covering much of his career. There are also archival interviews with Montand (1970, 7:11) and Artur and Lise London (1981, 11:26), as well as new interviews with film editor Francoise Bonnot (17:14) and writer John Michalczyk, author of Costa-Gavras: The Political Fiction Film (7:32). The booklet essay is by film scholar Dina Iordanova.

The second disk contains only two supplements, a conversation between Costa-Gavras and critic Peter Cowie (31:07), which goes into the political background of State of Siege, and a selection of contemporary clips from NBC News about the kidnapping of Dan Mitrione (7:15). The booklet essay is by journalist Mark Danner, who writes about the real case of Mitrione and the uses to which the film puts those events.

Comments