Artsploitation Films and the boundaries of horror

In a genre as crowded as horror, with an almost guaranteed audience, all too often viewers are confronted with lazy filmmaking, over-worked formulas, an excess of cliches. With so many releases out there, it gets hard to find anything genuinely interesting. One of the advantages of writing a blog like this is that occasionally things come to me which I otherwise would probably never have heard of. Recently I started to receive press releases and links to on-line screeners from Artsploitation Films, a company I was unfamiliar with. From a brief sampling of their releases, their name seems appropriate. The three movies I’ve watched so far certainly contain exploitation elements – some gore, some nudity and sex – but all strive, with varying degrees of success, to push beyond familiar cliches,

The House With 100 Eyes (Jay Lee & Jim Rood, 2013)

I admit that I disliked Jay Lee and Jim Roof’s The House With 100 Eyes (2013). Despite a title which hints at a giallo pastiche, this is a found-footage mockumentary “made by” a middle-class serial-killing couple who cheerfully document their crimes on video. This is essentially torture porn played for comedy. That’s a very tricky act to pull off and, for me at least, Lee and Roof fail. The combination of graphic nastiness and jokey tone tasted sour in a way that, for instance, Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer managed to avoid; McNaughton’s film succeeds (very unpleasantly) because it takes the horror of the victims seriously. The House With 100 Eyes seems to think that the horror is a joke.

Horsehead (Romain Basset, 2014)

Much more interesting, though again not entirely successful, is Horsehead (2014), the first feature of a young French filmmaker. Romain Basset has ambition and a talent for visual flair which seems obviously influenced by Mario Bava and Dario Argento, particularly in his use of a heightened, saturated colour palette. The film’s weaknesses, though, lie in the overall conception and script and in what, to me, seems tonally inappropriate editing. The film is constructed around dreams, always a tricky thing to bring off, but instead of evoking a genuinely oneiric mood, Basset uses flashy, music-video style montage which is the antithesis of dream-like.

Jessica (Lilly-Fleur Pointeaux) returns home for the funeral of her grandmother after several years away. It is immediately apparent that her relationship with her mother Catelyn (Catriona MacColl) is highly strained; they can’t be together in a room for more than a few seconds before they start sniping at each other. Her stepfather Jim (Murray Head) tries to mediate, but the antagonisms run very deep. Catelyn disdains Jessica’s chosen field of study, “the psycho-physiology of dreams”, a gimmick on a par with Argento’s McGuffins in his early films; in this instance, the use (or misuse) of the concept of lucid dreaming drives the plot. Lucid dreams are ones in which the dreamer becomes aware that she or he is in a dream and is able to some degree to manipulate the dream’s events intentionally. In Horsehead “lucid dreams” are ones in which the dreamer has clairvoyant powers which reveal the hidden secrets of a family’s dark and twisted history.

Soon after arriving home, Jessica develops a fever (the film’s original French title) and slips into a hallucinatory state of mind in which she is pursued by the monstrous title character, a figure with a human body and the head of a horse (the first dream evokes Fuseli’s famous painting The Nightmare [1781]). In her dreams, Jessica begins to get hints about her own history; she has never known who her father was and her mother is hostile to any attempts to uncover family secrets. Catelyn uses increasingly harsh measures to stall Jessica’s enquiry, while Jim becomes increasingly concerned about the mother’s hostility to her daughter.

What is revealed by Jessica’s dreams, which make up the bulk of the film, is an unwholesome history of religious fanaticism, incest, infanticide and parental hatred for an unwanted child. But these dreams suffer from the common movie-dream problem of being constructed from overly obvious symbols which, rather than having the fluidity of genuine dreams, tend to be too specific and literary in their meanings; as visually striking as they are, these images have an air of simplified pop-psychology about them. Which is not to say that the film is without interest: Basset’s use of colour is quite striking and, despite a certain awkwardness in having shot this French film in English with a mixed cast, most of the performances are quite good. Pointeaux makes an appealing heroine (at times she reminded me of a young Kate Winslett), and it’s nice to see MacColl returning to a genre which gave her some success more than three decades ago (particularly the three movies she made with Lucio Fulci in 1980-81), but for which for many years she expressed some disdain. In Horsehead she gives a quite chilling performance as the emotionally distant mother. And Murray Head, an actor and singer best known as Judas on the original recording of Jesus Christ Superstar and as the bi-sexual Bob Elkin in John Schlesinger’s Sunday Bloody Sunday, adds a touch of human warmth and stability as Jim. This trio is well-supported by Gala Besson as Jessica’s grandmother Rose and Fu’ad Aït Aattou as her grandfather Winston (both of whom exist only in her dreams), Vernon Dobtcheff as George, a kind of family retainer, and Philippe Nahon as the local priest.

Artsploitation’s Blu-ray includes a one-hour making-of with some interesting behind-the-scenes glimpses of a low-budget production which stretched over two years. There are also four short films directed or co-directed by Basset.

*

Der Samurai (Till Kleinert, 2014)

If Horsehead hints more at fairy tale than outright horror, that intention is more fully realized in Der Samurai (2014), the second feature of German director Till Kleinert. This leans more towards something like Neil Jordan’s The Company of Wolves than the giallo, although unlike Jordan’s film, its symbolic evocation of sexual awakening is rooted in an initially recognizable real world – in this case, a small German town surrounded by woods. Jakob (Michel Diercks), born and raised in the town, is now a policeman who gets little respect from his boss or the people he grew up with. He says he likes the town, yet he’s obviously a bit of an outsider. But there’s also obviously something lurking beneath his quiet surface: at the film’s beginning, we see him taking a bag full of bloody raw meat out into the woods where he hangs it from a fallen tree as food for a wolf which roams the forest. He says that he does this to keep the animal away from people’s houses, but in effect he is forming a bond with the wild animal.

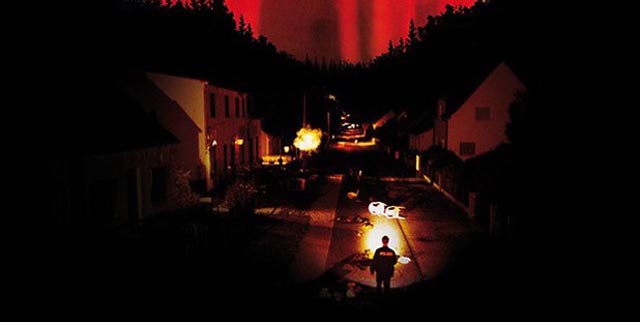

So far, more or less so ordinary. But the film slips into a different register when a package is delivered to the police station addressed to “the lone wolf” in care of Jakob; that evening he receives a creepy phone call from someone asking for the package and Jakob drives to a remote house in the woods where he finds a strangely threatening man wearing a dress and makeup; the stranger tears open the package and reveals a katana, the Japanese sword used by samurai. Thus begins a night in which Jakob’s placid world is ripped to shreds by the stranger (Pit Bukowski). At a superficial level, Jakob is dealing with a flamboyant killer who wreaks havoc in the town; on a symbolic level, he is dealing with something dark which he has summoned from inside himself. The narrative trajectory follows his gradual coming to terms with his own sexual nature, an identity he has kept repressed in the small town because he knows it won’t be accepted. In retrospect, many of the earlier scenes are expressions of sexual tension, rife with double entendres which show that his “secret” nature is more common knowledge than he’d like to admit.

As the samurai slashes his way through town, taunting and provoking Jakob, Kleinert maintains a fine balance between comedy and horror, between nightmare and a sense of liberation. He also avoids making the whole thing merely a subjective experience; yes, the samurai is a symbolic expression of Jakob’s inner turmoil resulting from repressed desire, but he’s no dream figure. In the film’s world, he exists as a physical entity summoned up and given corporeal reality by Jakob. This is where Der Samurai connects most closely to The Company of Wolves, and also to the traditional fairy tale.

Kleinert gets excellent performances from his cast, many of whom were quite inexperienced. Diercks manages to evoke a sense of innocence beneath which much darker currents flow, and Bukowski suggests a latter-day Klaus Kinski, combining dark humour with an intensely erotic presence, a disturbing combination of menace and attraction. Even the smallest roles seem perfectly cast, from Jakob’s disdainful boss (Uwe Preuss) to his dementia-suffering grandmother (Ulrike Hanke-Haensch) and his former schoolmate (Christopher Kane), for whom Jakob feels an obvious mixture of antagonism and attraction. The film is beautifully shot by Martin Hanslmayr on HD, most of it occurring at night, with saturated colours and rich contrast.

There has been a certain amount of criticism that Der Samurai is dangerously regressive in its sexual politics, but I think this negative view disregards the nature of fairy tales and their use in expressing and exorcising the darker aspects of human nature. Traditional fairy tales are often nasty and violent and horrifying, yet they allow for the working through of emotions not always acceptable to polite society. Der Samurai, to me, doesn’t seem to advocate killing “all that is effeminate inside” of Jakob (as one critic puts it); rather, in this symbolic world, the power of repression requires an explosion of violence to overthrow it … liberation is messy and painful, but nonetheless necessary.[1]

The Artsploitation Blu-ray has a brief behind-the-scenes featurette, but the really worthwhile supplement is a commentary track with Kleinert and co-producer Linus de Paoli; in very articulate English, the pair have a lot of interesting things to say about conceptual and creative issues as well as accomplishing an elaborate project on a very small budget. Most surprising was the revelation that Der Samurai was actually a “student project”, Kleinert’s final film school production. Its technical and creative accomplishments are all the more impressive for that.

Based on the range of content and quality shown by these three recent releases, Artsploitation appears to be a company worth keeping an eye on for works which push against the conventional boundaries of the horror genre.

Technical Note

While the Blu-rays of Horsehead and Der Samurai which Artsploitation sent me seem to be actual release disks, and not simply provisional screeners (both came in sealed cases with finished cover art), neither would play in either of my players (region A and multi-region); in fact both players wouldn’t recognize them as actual Blu-rays. However, both played perfectly on my desktop PC. I did email Artsploitation, but apart from acknowledging receipt of my puzzling complaint, I haven’t heard anything further, so I don’t know what caused this strange anomaly. The only visible difference between these two disks and the thousands of others I have is that the playing surface is black rather than silver, something I haven’t seen before. Without any clear explanation of the problem, I can recommend the content of the disks, but not the actual disks themselves.

_______________________________________________________________

(1.) (Spoiler) The full quote from Ed Gonzalez’ review at Slantmagazine.com is: “But the implications of the warped set piece are also unmistakably noxious, beginning with Jakob, realizing that he and the transvestite are one and the same. If so, call it hara-kiri when Jakob summons the courage to chase the transvestite through the woods and slice him to bits, though not before his tormentor has revealed to him his fully erect penis. Because in the fantasy world of Kleinert’s creation, a nebbish can only become a man once he’s summoned the courage to kill all that is effeminate inside of him.”

I see the ending somewhat differently. Reading the film as a “fairy tale”, yes, the samurai is a manifestation of Jakob’s own repressed sexual identity. Called up by Jakob, perhaps unconsciously, it expresses all the rage that repression has engendered. And, yes, at the end Jakob “kills” the samurai. But this is where I part from Gonzalez: as visually expressed in the film, when Jakob uses the samurai’s own sword to cut off his head, he isn’t destroying that part of himself – he’s releasing all that pent up energy and claiming it for his own. At the end, he and the samurai have become integrated, with Jakob owning up to his own nature. Birth and rebirth are a bloody business and fairy tales tend not to gloss over that fact; they exist to enable us to accept the harsher facts of life. That the ending is actually a form of acceptance is signaled by the scene shortly before the end when Jakob finally finds it in himself to engage with the samurai on his own terms in an erotic dance by firelight. Jakob isn’t quite there yet (he does this in order to hold the samurai until the forces of order can arrive and re-contain him), but after this he is no longer able to sustain his resistance to what the samurai represents.

It seems to me that the final image of Jakob in the woods, using the katana in the kind of ritual display familiar from samurai movies, is not an indication of the triumph of some kind of hard masculinity; it does however suggest that the newly integrated Jakob in embracing his sexual identity now poses a threat to the society which had previously required him to suppress that identity – not because he has now become violent, but simply because his existence will force that society to change. He has become a symbol of “disorder” rather than of the repressive order he represented as a policeman. (return)

Comments