Recent disks from Arrow Video

Unlike major corporations, which release their own mainstream productions on disk, smaller independent labels take on their own distinctive personalities through their choice of titles to distribute. I find that in recent years I have tended to be drawn to releases partly because of who is issuing them. Going back to the days of laserdisk and on into the early years of DVD, Criterion was the preeminent such label and they continue to maintain an impressive catalogue, although their implicit intention to be “canonical” has at times made their selections seem narrower and more limited than some newer labels – this is partly due to the fact that they can only release so many titles and the range and number of possible options is immense, but also partly due to the dedicated core market they have nurtured over thirty years. When they have strayed slightly from that original canonical aim, reaction has sometimes been intensely negative – perhaps most vehement in the case of their lavish editions of Michael Bay’s The Rock and Armageddon. The outrage was palpable. (Confession: I tend to re-watch both those disks about once every two years.) But there was also criticism of choices which in terms of film history may have been more justified, although the works in question may not exactly be “art”. Like the Richard Gordon box set of sci-fi and horror B-movies Madmen and Monsters, and its stand-alone companion Fiend Without a Face; or the ambitious “amateur” project Equinox, given a remarkably detailed release which illustrated the origins of the ’70s SFX boom in the enthusiasm of ’60s kids determined to figure out the possibilities of film illusion for themselves. Co-created by Dennis Muren, who went on to become one of the key effects technicians of the blockbuster era, Equinox may not be a major movie, but as Criterion’s presentation shows, there’s more to film history than the slippery attempt to nail down a canon.

In recent years a number of newer labels have been giving Criterion some significant competition, while not being hampered by that image of respectability. These are labels which often concentrate on the more disreputable levels of the business, while giving their chosen titles a stature those movies seldom received when originally released – in the early days of DVD, Anchor Bay was a major player in this area; when AB began to falter, Blue Underground took up the genre title slack. As these companies faded in significance, competitors proliferated, some lasting longer than others – Subversive Cinema, Dark Sky, Severin Films, Shout! Factory, No Shame, Scorpion Releasing, Grindhouse Releasing, Drafthouse Films. At the more respectable end of the scale, edging into Criterion territory and even matching that gold standard, are the Cohen Film Collection, Eureka/Masters of Cinema, the BFI, Milestone Films, Flicker Alley, and increasingly Twilight Time. But my favourite company these days is Arrow Video in the UK (which has recently branched out into the North American market), a label which has made huge efforts in the past few years to expand its range of releases while increasing its commitment to providing the best possible technical quality and substantial contextual supplements.

Something like the love child of Criterion and Shout! Factory, Arrow is a company dedicated to rediscovering and preserving the best in international cinema (their remarkable effort to “rediscover” Walerian Borowczyk and place him where he belongs in the canon; impressive editions of De Sica’s Miracle in Milan and Bertolucci’s The Conformist) as well as both the high and low ends of genre, particularly Euro horror (the Spirits of the Dead omnibus, an on-going library of Mario Bava’s works), early Cronenberg and Jack Hill … this is a company run by people who love movies and unselfconsciously lavish the same degree of attention on acknowledged classics and unapologetic exploitation, and in so doing make it clear that these are not always mutually exclusive categories. Filmmakers working in the lower depths can also be artists, just as artists can work with materials not always acceptable to polite society.

In addition to Arrow titles I’ve written about recently (the Borowczyk set, Cronenberg’s Shivers and Rabid, Jeff Gillen and Alan Ormsby’s Deranged, Joe Dante’s The ‘Burbs), in the past month or so I’ve also immersed myself in the following disks:

Sisters (Brian De Palma, 1973)

Brian De Palma began his long career with several counter-culture comedies (Hi, Mom!, Greetings, The Wedding Party), starring Robert De Niro at the beginning of his career, and a couple of avant garde/experimental works (the filmed stage play Dionysus in ’69 and Murder a la Mod, a tonally chaotic experiment with cliches of form and content which first exhibited his attraction to Hitchcock as a model; the latter is available on Criterion’s Blow Out Blu-ray). After his initial somewhat disastrous step into the mainstream, the studio-produced comedy Get to Know Your Rabbit, De Palma made the first film which marked his distinctive combination of independent experimentation and deliberate genre exploitation, applying stylistic innovation to thriller elements which would lead him to be (inaccurately) accused of being a slavish imitator of Hitchcock. While certainly influenced by the Master of Suspense, De Palma showed his own distinctive personality and obsessions (cinematic and sexual) in his early features. While these characteristics gradually atrophied over the duration of his career, they have remained his own.

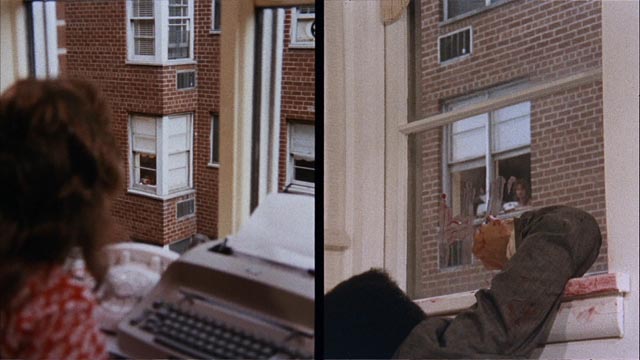

Certainly, Sisters – like other films which followed – draws on Rear Window and Psycho in some of its plot mechanics, but its themes are De Palma’s. The director has repeatedly returned (like Hitchcock) to the inescapable element of voyeurism implicit in cinema, here beginning the film explicitly with what turns out to be a voyeuristic TV show like Candid Camera and extrapolating from that to a brutal murder witnessed from one apartment through the window of an opposite apartment which frames the violence like yet another screen.

De Palma has quite frequently been accused of misogyny, but this film contains an overt critique of male attitudes towards women – both in the antagonism of the police towards the heroine Grace Collier (Jennifer Salt), a local reporter who has criticized police racism and brutality in print, and in the possessive paternalism of Dr. Emil Breton (De Palma favourite William Finley) towards Danielle (Margot Kidder), the woman at the heart of the film’s mystery. Perhaps for the only really appropriate time in his career, De Palma uses split screen extensively to visually represent the psychological division between Danielle and her dark twin Dominique (also Kidder). Despite the obvious psychological problems of the twins, Dr. Breton turns out to be the most deranged character in the story, while the other main male figure, private detective Joseph Larch (Charles Durning), is played as a comic buffoon. It’s the women who hold the narrative centre, in the end tragically for both because the men in this world refuse to acknowledge their right to exist on their own terms.

Sisters has its rough edges, but it remains one of the most accomplished films of De Palma’s career. Arrow’s Blu-ray is the most recent of their De Palma releases, preceded by editions of Phantom of the Paradise, Obsession and The Fury. The disk includes a visual essay by Justin Humphreys, several interviews with people involved in the production, an audio interview with the late William Findley, and a survey of De Palma’s career by critic Mike Sutton.

*

Bob Hoskins double feature

Arrow’s collector’s edition of John Mackenzie’s The Long Good Friday (1980) contains as a “supplement” Neil Jordan’s Mona Lisa (1986), thus encapsulating what remain the late Bob Hoskins’ two signature performances. Following a decade of television work, including the lead in Dennis Potter’s remarkable Pennies From Heaven (1978), and a few minor roles in features, Hoskins achieved a sudden and unexpected international stardom when he lit the screen in Mackenzie’s film with his performance as ambitious London gangster Harold Shand. As scripted by Barrie Keeffe, the story of Harold and his equally ambitious wife Victoria (Helen Mirren), trying to impress a representative of the U.S. Mafia with plans to go legit by developing London’s docklands while unknown forces begin to destroy his organization over the Easter weekend, became a prescient metaphor for Thatcherism before that insidious political development actually got underway. Harold represents rampant capitalism and the ways in which it set about to “rebuild” London by destroying the past in the name of private profit. Unfortunately for him brutal political reality (in the form of the IRA) derails his plans. (But this turned out to be a temporary setback as it wasn’t too long before the IRA was tamed and brought into the political mainstream, while multinational capital transformed London into a glittering symbol of national identity swept away by the interests of the global 1%.)

Hoskins is riveting as Harold, a chilling amalgam of sentiment and brutality who stands as one of the screen’s great gangsters. His George in Neil Jordan’s film is the flipside of that coin, a small-time London crook who has just emerged from a lengthy prison sentence and finds his old haunts totally changed. Distanced from his now teen-age daughter, who has never been told where he disappeared to, he finds his neighbourhood “taken over” by immigrants. His casual racism is mixed with a sentimental view of the way things used to be. But things have changed. Traditional criminality (though it’s never explained just what it was he was sent to prison for) has been displaced by new “business”, both more sordid and more profitable. George’s sense of thieves’ honour is hopelessly out-moded.

Whatever George was put away for apparently involved doing his boss a favour by voluntarily taking the rap; when he gets out, George goes looking for that boss, Mortwell (Michael Caine), expecting some compensation. What he gets is an assignment to drive a classy black call girl to her various jobs. George’s innate and unselfconscious racism and sexism is gradually undermined as this enforced relationship brings out his own romanticism. He becomes infatuated with the enigmatic Simone (Cathy Tyson) and she in turn begins to mold him into someone less crass. His confusing emotions blind him to the fact that she is actually using him for her own ends – that is, she gets him to track down a teenage hooker who used to work with her for a violent pimp before she moved up in the world. George’s romanticism and his own connection with a teenage daughter transform him into a kind of avenging crusader, appalled by the drugs and prostitution which are destroying young lives.

The parallels with Taxi Driver are both obvious and deliberate, but in Mona Lisa the protagonist, rather than being a deranged psychotic, is a displaced Quixote, too blinded by his own sentimentality to see that he’s been sorely used by a woman he never really understands. He walks away from the bloody climax sadder and perhaps wiser, and maybe better able to establish a more lasting relationship with his daughter.

There’s a tension in Mona Lisa between the sordid world it depicts and the softer, more sentimental treatment of the central character. As in a number of his other films, Jordan deliberately moves away from realism, preferring instead to fashion a kind of urban fairy tale. His treatment of London as a phantasmagoric dreamscape is lush and often quite beautiful, even as what is depicted is sordid – the bridge where George and Simone search among the lost children looking for the missing Cathy (Kate Hardie); the sleazy backstreets of Soho; Mortwell’s house where George finally rescues Cathy from her horrible sexual servitude.

I have to admit, though, that for all its fine qualities for me Mona Lisa is the lesser film, largely because I can never quite accept Bob Hoskins as such a naif. There’s too much intelligence and self-awareness in the actor’s eyes to be entirely convincing as this rather thick but essentially nice guy. Which is not to say that there aren’t moments of brilliance in the performance, particularly towards the end as the truth of Simone’s manipulation finally dawns on him. The sequence where his infatuation turns to rage on the Brighton Pier is one of the film’s highlights. But most of all, I like the quieter scenes in which George spends time with his peacefully contented friend Thomas (Robbie Coltrane), who throws himself into an endless stream of get-rich-quick schemes which provide the film with some of its most surreal images. The rest of the cast is also superb, from Cathy Tyson in her first feature to Michael Caine, relaxed well into his career, playing a character similar to the one playwright John Osborne played as Caine’s nemesis in Get Carter (1971). Clarke Peters is chilling as the vicious pimp Anderson, and Kate Hardie and Sammi Davis are deeply affecting as two teenage prostitutes, as is Zoe Nathenson as George’s daughter Jeannie.

Arrow’s collector’s edition presents both films in gorgeous hi-def transfers which together provide a fascinating time capsule of London both at the beginning and towards the end of Thatcherism – a world of glittering capitalist promise which quickly collapses into the vilest realms of exploitation. Both films have commentary tracks (The Long Good Friday with John Mackenzie, Mona Lisa with a joint track by Jordan and Hoskins[1]), plus a lot of interview-based supplements, including Bloody Business, a long making-of previously available on Anchor Bay’s Long Good Friday special edition DVD. A particular treat is Mackenzie’s half-hour “public service” short from 1977, Apaches, a chilling and somewhat surreal warning of the dangers children face around farmyards, previously available on volume four of the BFI’s Central Office of Information series of DVDs, and here presented in a new hi-def transfer.

The set comes with a small 100-page hardcover book containing new essays, contemporary reviews, and lively and informative chapters on the making of each of the features excerpted from Robert Sellers’ history of Handmade Films, Very Naughty Boys (Titan Books, 2013).

*

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Miss Osbourne (Walerian Borowczyk, 1981)

In their continuing rehabilitation of the Polish director Walerian Borowczyk, Arrow have skipped over the five features which followed The Beast (which is where their amazing box set ends) in order to give us The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Miss Osborne (1981), a richly idiosyncratic version of Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous novella, and one of the best. Borowczyk claimed at the time (tongue firmly in cheek) that he had discovered the famous lost first draft of the tale, supposedly written in a drug-fueled frenzy and burned by his wife Fanny Osbourne, who was appalled by its blatant eroticism. Although the story as we know it centres on the duality between intellect and animal instinct in human beings, the erotic element has always been understood and comes out in virtually every movie adaption (pretty much the first thing Hyde does in every version is head for disreputable saloons and music halls where he takes up with prostitutes and show girls).

Borowczyk’s version remains almost entirely confined to Jekyll’s house and takes place over a single night, starting in fact on the evening of the party to celebrate his engagement to Miss Osbourne. Jekyll (the always fascinating Udo Kier) is addicted to his chemical formula and the license it grants him to express his most sordid desires. As the party continues, he keeps vanishing into his lab, while the vicious figure of Hyde emerges to murder and rape and prod the various guests to express their own repressed violence and sexual desire. Victorian propriety is laid waste and hypocrisy exposed. Although lushly atmospheric (the film was shot by Borowczyk’s long-time collaborator Noel Very), at times horrific and perverse, Borowczyk treats the story as black comedy, furthering the assault on bourgeois manners which marked much of his earlier work (his work here and in The Beast has strong affinities with Bunuel). Gerard Zalcberg as Hyde provides the icing on this confection of horror and comedy as perhaps the most disturbing version of the character ever to show up on screen.

Despite the mix of nationalities and issues of dubbing familiar in this kind of international production, the cast is quite impressive, with Kier, Zalcberg, and Marina Pierro (as Miss Osbourne) as stand-outs. The idiosyncratic Howard Vernon (as Dr. Lanyon) and Patrick Magee (as General William Danvers Carew) are a delight. While the English-dubbed track is perhaps less pleasing than the French, it does have the advantage of using Magee’s own distinctive voice.

Although this film was made long after Borowczyk had lost critical favour and been dismissed as a high-class pornographer, Dr. Jekyll and Miss Osbourne is beautifully directed and shot, with far more atmosphere than any of Hammer’s period horrors. It also has the most inventive and original transformation sequences ever conceived for this story.

Once again, Arrow have packed the disk with supplements, including a commentary cut together from an archival interview with Borowczyk and newer contributions from several of the director’s collaborators; interviews with Kier and Pierro; a video essay by Adrian Martin and Cristina Alvarez Lopez; featurettes on Borowczyk’s collaborations with composer Bernard Parmegiani and on the director’s connections with early cinema; Happy Toy (1979), an animated short in which Borowczyk pays erotic homage to the pre-cinematic praxinoscope; Himorogi (2012), a short film made in homage to Borowczyk by Marina and Alessio Pierro; plus a few other odds and ends. An excellent companion to the box set, we can only hope that this release means that Arrow will continue to restore Borowczyk’s features and gradually make all his films available on disk.

_______________________________________________________________

(1.) I have to express some gratitude to Arrow because in the Mona Lisa commentary track, Neil Jordan explains that the somewhat cryptic comments Thomas makes about a book he’s reading refer to a 1946 novel called The Deadly Percheron by John Franklin Bardin. I looked the author up and discovered that his first three novels – The Deadly Percheron, The Last of Philip Banter (1947) and Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly (1948) – are available from Amazon for Kindle really cheap. I bought all three and read them back to back in about ten days; Bardin was a remarkably inventive writer and these three very different novels are some of the best reading I’ve come across in years. (return)

Comments