My adventure with Jack Nance on the fringes of Hollywood

I recently came across a small stash of old audio tapes. These were copies of several interviews I conducted while working on Dune back in 1983. I dubbed them from the original video tapes that Anatol Pacanowski and I shot while we were documenting the production for Universal Studios. I’m not sure now why I made the dubs – perhaps it was due to some premonition I had that the video tapes would be taken away from us, though I didn’t imagine at the time that the studio would destroy them all a couple of years later. Whatever the reason, these rather poor-quality dubs are all that remain of the Dune making-of documentary. Although I don’t think the interviews are very good (I didn’t know what I was doing when they were recorded), if I can find the time and energy, I may transcribe them and post the text here on my site as an additional element of my record of that summer in Mexico City. (These transcripts are now available as part of my book about my Dune experiences.)

I have just over four hours of recordings of David Lynch, Max von Sydow, Jurgen Prochnow, Patrick Stewart, Sting and Sean Young, plus John Dykstra, Bob Bealmear, Giorgio Desideri and Aldo Puccini. Some of the interviews we did are missing, though whether that’s because I didn’t make a dub at the time or have since lost the tapes, I can’t say. The most significant absences are cinematographer Freddie Francis and the film’s star Kyle Maclachlan. The longest session was the one we did with Jack Nance one afternoon after lunch at Estudios Churubusco, when we were all a bit drunk. I can recall Anatol setting the camera up, with Jack perched on a chair and the rest of us lying on our office floor while we talked randomly about whatever popped into our heads.

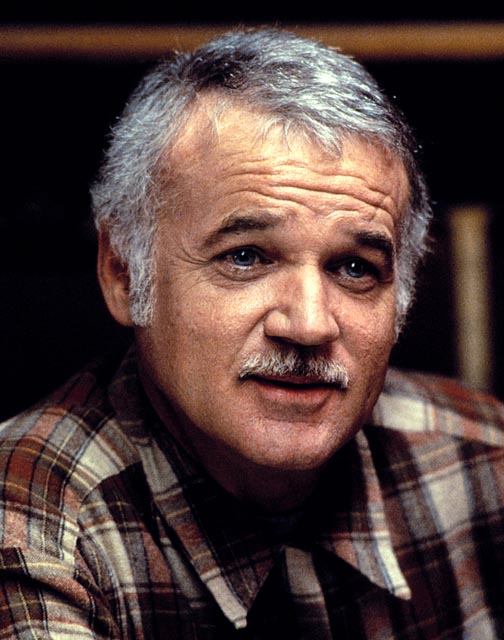

My brief connection with Jack Nance in the ’80s was one of the most important things to come out of my research on Eraserhead and my work on Dune. Jack was unlike anyone else I’ve ever known, one of the most charming and amusing people I’ve ever met; but that charm could be washed away when he was drinking. I saw him bright and intelligent, self-deprecating about his considerable talent; and I also saw him angry and even violent, looking for a fight as if he had some dark energy trapped inside which needed to explode out of him to relieve an intolerable pressure. Truth is, Jack was the first serious alcoholic I ever met and I found the pattern of mood swings confusing; he was like two completely different people, one I loved dearly, the other seriously scared me.

I first met him when I went to Los Angeles in December 1981 to conduct interviews for my article about the making of Eraserhead. The long lunchtime session at a Denny’s on Sunset Strip was a highlight of my trip. As an added bonus, a day or two later he got me into Zoetrope Studios where I watched Wim Wenders at work for an afternoon on the Chinatown set of Hammett, a movie in which Jack had a small role. But after I returned to Winnipeg a few days later, I had no more contact with Jack until he arrived in Mexico City in late May 1983 to play Nefud in Dune (a role invented by David Lynch specifically to give Jack some work). He remembered me from the meeting a year and a half earlier and I gave him a photocopy of the typed manuscript of my article. He liked it so much that we became instant friends and I hung out with him a lot over the next three months. Which meant a lot of evenings out at bars, in one of which I first saw his dark side. But the next day he was his “normal” self again.

He told me about a project he wanted to get off the ground, a movie about a famous Texas gambler and gangster named Herbert Noble, nicknamed “the cat” because he survived so many attempts on his life. I actually still have a tape that Jack made for me on which he reads through his large collection of newspaper clippings about Noble. (Listening to his voice on that tape brings back vivid memories of the charming, impish Jack.) The idea of a movie about Noble never got beyond Jack’s dream. Another project we discussed never got much beyond my own dream.

When principal photography concluded on Dune in early September 1983, and Universal took away all the tapes Anatol and I had shot, I returned to Winnipeg, pretty much kicking myself all the way for not having handled things better; Anatol and I never even had written contracts for the job we were hired to do and so were without rights and protections, despite verbal agreements with executives at the studio. The most amazing opportunity I’d ever been given ended ignominiously because of my own inexperience. But I kept in touch with Jack, by letter and occasionally by phone, and met up with him again in December 1983, when I took a brief detour to Los Angeles to see Jack Leustig, Kyle Maclachlan’s agent, who had optioned the script I wrote during the summer in Mexico. That was when I got to see where Jack lived, a kind of scary apartment with a mound of trash spilling across the kitchen and a ragged old couch inside of which his pet rat lived.

When I was drifting around Europe in the summer of 1984, I wrote a long treatment for a script about a character based on Jack. It was a mix of sci-fi, noir and comedy, about a washed up, alcoholic detective who gets reluctantly drawn into a case when a young woman comes looking for help. Not an original premise, perhaps, but it goes off in unexpected directions involving cutting edge media and an invention which can open doorways in time and across dimensions. I turned the treatment into a script when I got back to England after fourteen weeks in Italy, Germany, Denmark, Holland and Belgium and sent a copy to Jack. I was a bit nervous that he’d take offence at what might be considered an unflattering portrait of him, but he actually acknowledged that I’d captured him quite accurately. He liked it, so we tried to figure out what to do with it – while he was a character actor with a cult following, I was nobody with essentially no experience. We didn’t have a lot to build on!

I worked on polishing the script some more and Jack sent out some feelers, eventually getting a glimmer of interest far from Hollywood. Jack’s brother Richard was a lawyer with business connections in the southwest and he had become involved with a consortium of Oklahoma ranchers who were getting a lot of money in royalties from oil wells on their land. And these ranchers were looking around for ways to invest that money which would help them avoid paying some taxes. Someone had suggested that the movies might be a good bet for generating some profitable tax write-offs and, one thing leading to another, my script was offered to them as a possible investment. Which is why I suddenly found myself in May of 1985 flying down to Los Angeles again.

I think it was a ten-day to two-week visit. I stayed a while again with Jack Leustig and his wife Elisabeth, and also crashed for about a week at Kyle Maclachlan’s apartment. But the main point of the trip was a one day excursion to Las Vegas to meet with Richard and a representative of the Oklahoma oilmen. Jack and I were put up at some casino hotel (I can’t remember which one), given some spending money and tickets to a show which, the representative told us, had some on-stage effects which would be ideal for the script’s time/dimension-traveling sequences. I can’t recall anything much about the show other than that it looked like numerous such shows I’d seen in movies: part magic, part cabaret, populated by long-legged dancers wearing glitzy yet skimpy outfits. I think there was a tiger involved too. The “effects” we’d been told to watch out for were just a scanning laser and stage smoke which produced a kind of swirling, liquid light … something already used in quite a few movies, so hardly ground-breaking.

But this was all mere preamble. The point of the visit was the meeting where we were going to discuss the project, what it entailed, ballpark some budget numbers and maybe toss around a few names of people we’d like to have involved. This took place in the representative’s hotel room, with me, Jack, Richard and someone else present. I can’t remember the representative’s name, but he was a classic “good ol’ boy”, well over six feet tall, heavyset but giving an impression of being fit. He spoke with a big voice and even wore cowboy boots and had a hat. And it quickly became clear that he hadn’t come with the same intention as Jack and me.

He immediately took out a copy of the script and opened it to page one. Then he proceeded to go through it line by line, objecting to individual words – and not just in the dialogue, but also in the scene descriptions. After his first comment about an inappropriate word, he paused and looked at me expectantly. Then he asked if I was going to write it down so I’d remember. I half-heartedly scribbled on a page of my notebook. A bit later, when he objected to a particular adjective in a scene description, I tried to explain that those parts would not actually be heard by an audience, but he still thought it should be removed because it was giving “the wrong impression”.

Jack and I kept looking at each other; Richard started to look embarrassed. And I didn’t have a clue how to handle the situation. Here was a guy who may have the power to make money available to us, so I didn’t want to offend him by saying outright that we weren’t there for detailed yet dumbass script notes, yet he was utterly impervious to any subtle nudges towards a more practical conversation. In short, this guy knew nothing about movies, nothing about either the business or creative side of filmmaking. But he was working overtime to impress us with his deep thinking about the script. It was excruciating and I was rapidly getting more and more depressed. This all started sometime shortly before midnight and went on for several hours. I think it finally stopped because he’d simply become bored. As I recall, though, he did make it to the end of the script.

I think it was well after three that the “meeting” broke up. Jack and I went downstairs to the casino, where we ordered drinks and stared at each other. There didn’t seem to be much to say. Jack went over to the craps table and started shooting dice. I stuck around a little longer, then went up to my room and tried to sleep. I was pretty restless and eventually went down to the restaurant, where I met Jack for breakfast around 7:00. The oilmen’s representative joined us, big and loud and seemingly unaffected by a lack of sleep, though both Jack and I were pretty exhausted.

He offered something like a priceless piece de resistance at the breakfast table, taking a pen from his jacket pocket, flipping over his placemat, and quickly sketching what looked like a football play diagram as he explained in all seriousness that you couldn’t trust directors, so we had to work out a strategy to make the movie without allowing the director to make any decisions. He used little figures and arrows to show us how we had to “get around the director”, because a director would only waste our money.

Jack and I caught a 9:30 A.M. flight back to Los Angeles.

I think we waited about three months to hear back from Richard. The good ol’ boy had reported back to his ranchers and eventually they all decided to put their money into real estate.

Jack and I kept in touch on and off for a few more years. I turned the script into an (unpublished) novel, eventually doing a major rewrite of both script and novel in which I changed the gender of the protagonist.

Jack was in a cycle of drinking and sobriety and back to drinking again in those years[1]. He moved around quite a bit and eventually I lost touch with him. I probably hadn’t heard from him in about seven or eight years when I read a brief newspaper report of his death in 1996. The circumstances seemed peculiar, and yet remembering how he could be when he’d been drinking, aggressively getting in the face of people a lot bigger and stronger than himself, I could picture him in that donut shop parking lot getting into an argument with some guy who punched him in the face and knocked him down. Apparently the police never found evidence of a fight and we only have a second-hand account of what may or may not have happened from someone Jack told the story to later that day. The next morning he was dead.

_______________________________________________________________

Comments

I just found your site today via a link to my column on Herbert “the Cat” Noble. Love your memories and musings on the backstory of Hollywood. Please keep the stories coming. Thanks.

— Nolan Dalla

Thanks, Nolan. It was interesting to discover when I found your own site that Jack wasn’t alone in his passionate interest in the life of Herbert Noble. It does seem surprising, though, given Noble’s story, that no one has yet made a movie about such a larger than life character.