Twilight Time: Fantasies of romance

Twilight Time recently released two 1960s romantic comedies on Blu-ray. One is a prestigious production with a major director, a high-powered cast, and a mission to change to minds of its audience; the other is a modest film by a relatively new director which stars two unknowns, although it’s top-lined by a major, but miscast star. The big movie is very stagy and old-fashioned in form; the small one, fresh and stylistically inventive. And yet, even though Stanley Kramer’s Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner sets out to tackle the deeply rooted problem of racism in America, it’s The World of Henry Orient, George Roy Hill’s whimsical depiction of adolescent infatuation, which ends up entering much darker emotional waters.

The World of Henry Orient (1964, George Roy Hill)

George Roy Hill was one of those odd Hollywood filmmakers: a director whose work seemed to have no distinctive personality, yet who managed to make a string of movies which were commercially successful and also won quite a few awards, though critical reception wasn’t unanimously positive. His biggest hits were his collaborations with Paul Newman – Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), The Sting (1973) and Slap Shot (1977); he worked in many genres (comedy, western, historical epic, musical, science fiction) and much of his work was adapted from novels and plays. Personally, I prefer a pair of less commercially and critically successful movies, Slaughtehouse-Five (1972) and the underrated The Great Waldo Pepper (1975). In effect, although he began his big screen career (after almost a decade in television) as the big studios were being dismantled, he seems more like a classical studio director than the kind of “auteur” who was becoming dominant in the less structured industry of the ’60s.

Following his first two features, a pair of somewhat stagy play adaptations – Tennessee Williams’ Period of Adjustment (1962) and Lillian Hellman’s Toys in the Attic (1963) – Hill made one of his most original films, one which shows him opening up and playing the medium with an often exhilarating sense of freedom. The World of Henry Orient (1964) is, as Julie Kirgo points out in the commentary included on Twilight Time’s Blu-ray release, that rarity, a girls’ coming of age story. Based on an autobiographical novel by Nora Johnson, whose father was Hollywood legend Nunnally Johnson, who collaborated with his daughter on the adaptation, the film has a very distinctive flavour rooted in the imaginations of its two young protagonists. Marian “Gil” Gilbert (Merrie Spaeth) is a bit of a misfit, her parents divorced, living in New York with her mother Avis (the lovely Phyllis Thaxter) and her mother’s friend “Boothy” (Bibi Osterwald); the completely unspoken suggestion of a lesbian relationship is one of the film’s most striking notes. Valerie “Val” Campbell Boyd (Tippy Walker), on the other hand, has a pair of wealthy parents who are always off traveling around the world, leaving her in the hands of caretakers in a large apartment which completely lacks the cosy atmosphere of Gil’s home.

Val, possibly a child prodigy on the piano, has developed an infatuation with concert pianist Henry Orient (Peter Sellers) and under Gil’s influence, the two girls essentially begin to stalk the musician, popping up to interrupt his attempts to seduce the married Stella Dunnworthy (Paula Prentiss) – in Central Park, in a small intimate restaurant, in his own apartment. The girls never actually meet Orient, their relationship to him remaining a fantasy of romance, although their presence triggers increasingly paranoid fears in him.

This dream of romance is shattered with the return of Val’s parents, businessman Frank Boyd (Tom Bosley) and socialite Isabel (Angela Lansbury). Just two years after The Manchurian Candidate, Lansbury appears as another of the most monstrous mothers in American film. Icy, egotistical and contemptuous, she projects her own illicit feelings onto Val when she discovers the scrapbook which enshrines her infatuation with Orient. Unable to comprehend the nature of her daughter’s imagination, she believes that an actual sexual relationship exists – that, in fact, her adolescent child is a “slut”. Here, the film’s frothy, uninhibited comedy takes a darker turn, made worse when Isabel goes to confront the pianist and immediately becomes his lover, something discovered by Val in the film’s most emotionally devastating moment.

Although the story’s complications are resolved in a satisfying way, the ending also contains a note of bittersweet loss as the two girls shift beyond that free-floating moment of adolescent possibility and settles into a more conventional and predefined teenage realm; in the final scene, the two girls are together in Val’s bedroom experimenting with makeup and talking excitedly about boys. There is a sense that growing up involves a kind of closing down, and the film’s earlier playfulness takes on a retrospective air of nostalgia.

That sense of nostalgia, by the way, is heightened by the location shooting in New York, which manages to give the film a fairytale ambiance, heightened by the girls’ complete freedom to roam at will in a way which would seem utterly impossible today.

Although The World of Henry Orient (as the title suggests) headlines Peter Sellers as the frustrated Lothario, the film undeniably belongs to the two girls. Spaeth and Walker, neither of whom had acted before, have that wonderful untutored talent which allows them to seem entirely natural and unselfconscious and they give the film its ebullient energy. Sellers, on the other hand, working between Dr. Strangelove and A Shot in the Dark (both made the same year), seems like a distraction, a mannered rather than natural presence, and the film occasionally distorts itself to foreground some bit of comic business focused on him. Perhaps the most surprising thing about Twilight Time’s release is the rather passionate attack Nick Redman launches into on the commentary track, in which he completely tears down Sellers’ reputation as a comic genius. While I was initially a bit shocked, I must admit that in the end I was hard put to contradict much of what he says: while Sellers appeared in a number of very good films, too often he resorted to shtick rather than characterization. His finest work was in Dr. Strangelove, interestingly a film which was rooted in caricature rather than realism (Redman singles out the actor’s work for Kubrick as his only notable performances, including his Clare Quilty in Lolita, but personally I’ve always found Quilty to be the biggest false note in that Nabokov adaptation). Hill’s film might be even better if someone else had been cast as Henry Orient.

*

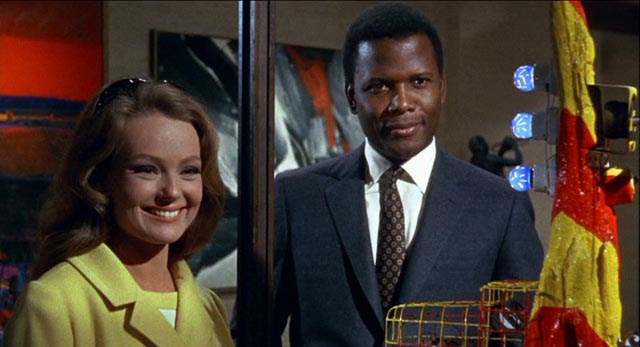

Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967, Stanley Kramer)

Unlike George Roy Hill, Stanley Kramer had his roots planted deeply in the Hollywood studio system, going back to the early ’40s as a producer and the mid-’50s as a director. Yet, he came to stand somewhat apart from the studio mainstream because of his insistence on using movies as a vehicle to promote liberal ideas. Why leave the message to Western Union, when you could embed it in a piece of popular entertainment which would reach far more people?

I mentioned Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, Kramer’s last big success (before a decade of decline), in passing in a recent post about blaxploitation movies. That comment was made in the context of my recent reading of James Baldwin’s essay about Blacks in American film, The Devil Finds Work. Although I hadn’t seen the movie since I caught it on television sometime in the early ’70s, I was rather dismissive (my attitude was rooted in the general critical opinion of the film as naive and simplistic). But I’ve just watched it on Twilight Time’s new Blu-ray edition and now find my reaction somewhat more complicated.

Is Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner a “good” movie? It was nominated for ten Oscars (and won two) and seven Golden Globes (winning none), as well as numerous other nominations and occasional wins around the world, as well as being one of the year’s biggest box office hits. Was all that attention due to its taking on a controversial subject, interracial marriage (still illegal at the time of production in many Southern states, although the Supreme Court ruled that illegality unconstitutional around the time of the film’s release)? Although only briefly glimpsed in the first few minutes (in a taxi’s rearview mirror), the film provided the American big screen with its first interracial kiss (a bit later than the famous taboo-breaking Kirk-Uhura smooch in Star Trek).

Or was its popularity due to more mundane things? Watching it now, when the central concern has been stripped of much of its visceral power, at least for most viewers (the current President is the product of such a marriage), the film plays essentially as a sit-com. But within that limitation, it is undeniably entertaining, William Rose’s script packed with wit even though the characterizations are stereotyped. It even looks like a sit-com, shot almost entirely on a soundstage (even the patio overlooking San Francisco and the Golden Gate Bridge is an obvious interior set), with bright flat lighting and action staged more like a play than a movie, with characters entering and exiting several primary spaces, forming and breaking up various pairs and trios as the script works its way through its core argument.

The film was much-ridiculed at the time for the almost saintly portrayal of Sidney Poitier’s character John Prentice, a world-renowned doctor who selflessly devotes his life to the World Health Organization’s efforts to bring aid to suffering third world populations. The script also desexualizes him, the better to eliminate any lingering fears about the noxious stereotype of the rampant Black man threatening the purity of a white woman, in this case Joey Drayton (Katherine Houghton), the perky daughter of a rich newspaper owner and his society wife. At one point, when Joey’s mother Christina (Katherine Hepburn) uneasily skirts the question of sex, Joey brightly says that she’s willing, but John is determined to wait until they are married. Poitier himself was frequently criticized (sometimes in virulent terms) for his choice to portray this kind of character (Kramer’s film capped a remarkable year in which he also starred in To Sir, With Love and In the Heat of the Night, making him one of the most successful stars in the world), but as he often said, he felt a responsibility to portray his race in a positive light, a choice which did indeed open up American popular culture to Black performers; even if those who followed were able to portray more complex and conflicted characters, Poitier had done the groundwork which paved the way.

Kramer had a perfectly good argument for this key decision: he wanted to make Dr. Prentice so perfect in every way that the only possible objection Joey’s parent’s could have would be the colour of his skin, thereby exposing the potential hypocrisy of well-meaning liberals who preach equality while trying to avoid the inevitable consequences.

As Christina and her husband Matt (Spencer Tracey in his final performance) struggle to work out their feelings, the film complicates things with the reactions of other Black characters – the Drayton’s maid Tillie (Isabel Sanford), who is deeply suspicious of Prentice for stepping across a well-established social barrier, and John’s parents (Roy Glenn and Beah Richards), who are proud of what their son has achieved but fearful of what he’s risking by this socially unacceptable course of action. This is one of the film’s most interesting, but also risky, aspects: while the white liberals are virtually required by their political beliefs to accept the situation, the Black characters represent the internalized dimension of racial subjugation, a belief in “knowing one’s place”. This comes to a head in the powerful confrontation between John and his father which climaxes with John blurting out that his father thinks of himself “as a coloured man, but I think of myself as a man.”

In the end, it’s the women who make the film’s key argument, that what matters is individual feeling, not socially constructed barriers. Prompted by Joey’s colour-blind feelings, the two mothers overcome their own initial shock and eventually break down the fathers’ resistance, although matters are only finally resolved when Matt Drayton gathers everyone together and uses his patriarchal authority to tear down those barriers. This again is one cause of negative critical reaction – the use of a personal, emotional argument to counter deep-rooted social and political forces which have traditionally served to suppress Blacks in American society. This if anything marks Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner as naive, but it’s in keeping with the approach Hollywood has always taken towards social problems.

In the end, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner is a genuinely entertaining film whatever its weaknesses as a social document, its charm rooted in Rose’s impeccably constructed script and, more than anything else, in its wonderful cast. Although he may seem impossibly perfect, Poitier gives his usual intelligent and nuanced performance, confirming his status as one of the finest actors of his era. Perhaps key to the film’s popular success is the final pairing of Tracey and Hepburn, with the characters’ relationship deeply inflected with the actors’ own long-standing personal history as one of Hollywood’s most romantic (if illicit) couples. This pairing brings a huge weight of emotion to the film which enriches it beyond whatever intrinsic merits it may have; one’s response is deepened by the knowledge that Tracey was dying at the time (he did in fact die seventeen days after production wrapped), yet nonetheless gave a beautifully controlled and often subtle performance.

The supporting cast is uniformly excellent, with Sanford, Glenn and particularly Richards doing a great deal to prevent the movie from sliding into irredeemable liberal self-satisfaction. Even Cecil Kellaway, in the hoariest role as a charmingly outspoken Catholic priest right out of Leo McCarey’s sentimental playbook, manages to add life to the essentially artificial construct. As for Katherine Houghton, Hepburn’s niece, appearing in her first movie, she took a lot of flack, but it should be noted that she had a virtually impossible role as the perky avatar of a “post-racial” society, and yet she manages to give Joey enough charm and energy to convincingly set the whole machine in motion.

Twilight Time’s Blu-ray provides an excellent transfer, although the hi-def image fully reveals the rather flat TV look of the production. There are also several extras, including a couple of retrospective featurettes which sketch in the production’s history and reception. Disappointingly, the disk has one of the most unsatisfying commentaries yet offered by the company. Rather than the usual Nick Redman/Julie Kirgo track, we instead get a group commentary by film historians Eddy Friedfeld, Lee Pfeiffer and Paul Scrabo. This team, although they seem to be friends, trample all over each other with constant interruptions, so almost every time an interesting point is broached it never gets completed or explored because someone else can’t wait to jump in with their own thought. This constant chatter made me miss the usual respectful conversation we’ve come to expect from Twilight Time.

Comments

Great review of a groundbreaking film–only because it brought the issue to the mainstream and took a firm stand. Given a glossy, sudsy, star-studded treatment, with the impossibly beautiful and always impeccable Poitier as the stand-in for anyone of color, it is hardly controversial, but I guess that was the point. No grit here, amidst the ugliness on the streets and the violence and assassinations still to come. Love your blog!! My first time here!

Thanks … glad you found it!